Who were the Denisovans, archaic humans who lived in Asia and went extinct around 30,000 years ago?

These now-extinct humans lived as far back as 200,000 years ago.

The Denisovans, together with the Neanderthals, are the closest extinct relatives of modern humans. It wasn't until 2010 that scientists announced that the Denisovans existed, so much about them remains unknown. However, fossil and genetic evidence suggests the Denisovans lived across a wide range of areas and conditions, from the cold mountains of Siberia and Tibet to the jungles of Southeast Asia.

Denisovans' discovery

Russian scientists excavated the first fossils linked with the Denisovans (deh-NEESE'-so-vans) in the summer of 2008, in a site known as Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains in southern Siberia, according to the journal Nature. The cave was used as recently as the 1700s by a hermit named Denis, which is where it got its modern name — "the cave of Denis" in Russian, according to the Leakey Foundation.

Previous excavations at Denisova Cave discovered stone artifacts that decades of prior work suggested were Neanderthal in origin, according to Nature. As such, when scientists first unearthed the Denisovan fossils, they thought the remains belonged to Neanderthals.

However, subsequent analysis of ancient DNA extracted from these fossils revealed otherwise. In 2008, researchers sequenced the first complete genome of a Neanderthal, but a sliver of a 30,000- to 50,000-year-old finger bone from the cave belonged to a completely different, hitherto unknown human lineage. The scientists announced their discovery in a study in Nature in 2010.

"To show this from a tiny finger bone fragment was a remarkable technical achievement," Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London, told Live Science.

Denisovan evolution

The 2010 Nature study that revealed the existence of the Denisovans found that they were close relatives of the Neanderthals. A subsequent 2013 study in Nature estimated that the lineage that gave rise to the Neanderthals and the Denisovans split from the ancestors of modern humans between about 550,000 and 765,000 years ago. The ancestors of the Neanderthals and the Denisovans later diverged from one another between about 381,000 and 473,000 years ago.

"Denisovans and Neanderthals are the closest relatives of modern humans," Katerina Harvati, a paleoanthropologist and director of the Institute for Archaeological Sciences at the Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen in Germany, told Live Science.

A 2018 study in the journal Cell revealed that the Denisovans were composed of multiple lineages. One was closely related to the northern Siberian Denisovan and has a genetic legacy found primarily in East Asians. The other was more distantly related to the southern Siberian Denisovan and had DNA nowadays mostly seen in Papuans and South Asians. These groups split about 283,000 years ago. Although these Denisovan lineages shared a common origin with Neanderthals, they were nearly as genetically distinct from Neanderthals as Neanderthals were from modern humans (Homo sapiens).

A subsequent 2019 study in the journal Cell revealed a third Denisovan lineage. Based on the level of genetic differences among all three Denisovan lineages, this study suggested this third lineage separated from the other two about 363,000 years ago, and was about as different from the other Denisovans as it was from the Neanderthals. DNA from this third lineage was found primarily in modern individuals who lived on or near the island of New Guinea.

"I couldn't have imagined these exciting advances even 15 years ago — the pace and extent of developments has been so fast," Stringer said.

Denisovan specimens

Scientists have only a handful of Denisovan fossils. Researchers have identified eight small and highly fragmented Denisova Cave fossils as Denisovans based on their DNA. They include three molars; a bone chip from a long arm or leg bone; three bone slivers; and a fragment of a finger bone, the lone fossil to yield enough DNA for whole-genome sequencing.

Scientists have also discovered other Denisovan fossils that held proteins the researchers knew were Denisovan based on prior DNA research on the extinct lineage. These fossils include a jawbone from the Tibetan Plateau, a molar from a cave in Laos and a jawbone from Taiwan. A rib fragment found in Baishiya Karst Cave on the Tibetan Plateau also belonged to a Denisovan, according to an analysis of the bone's ancient proteins. This bone was dated to around 32,000 to 48,000 years ago, making it one of the most recent Denisovans on record.

One of the most prized Denisovan specimens is the "Dragon Man" skull from China. In 1933, a Chinese laborer in Harbin City found the skull and hid it in a well. Just before he died, he told his family, who found the skull in 2018 and donated the find to a museum.

In 2021, three studies that appeared in the journal The Innovation suggested, controversially, that the skull belonged to a new human species, Homo longi. At the time, many researchers wondered whether the skull was Denisovan. In 2025, two new studies found just that: Dragon Man was a Denisovan.

The skull, which is at least 146,000 years old, is one of the largest skulls of any known extinct human lineage. It could have housed a brain comparable in size to a modern human's, but it had larger, almost square eye sockets, thick brow ridges, a wide mouth and oversize teeth.

The more evidence of the Denisovans that scientists recover, "particularly from specimens yielding both DNA and morphological evidence, the higher the chances that we will be able to put additional, already known fossils in this group," Harvati said. "Paleoanthropologists these days are very mindful of potential genetic evidence while excavating, so the chances of recovering more such evidence are better than ever."

Denisovan interbreeding

A 2010 Nature study revealed that the Denisovans interbred with ancestors of modern humans, with their DNA making up about 4% to 6% of modern New Guinean and Bougainville Islander genomes in people living on the islands of Melanesia, a subregion of Oceania that includes New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, New Caledonia and Fiji. In contrast, the 2013 Nature study found that only about 0.2% of DNA of mainland Asians and Native Americans is Denisovan in origin.

Denisovan DNA may have conferred a number of benefits to modern humans. For instance, a 2014 Nature study discovered that a genetic mutation from Denisovans may help Tibetans and Sherpas live at high altitudes. A 2016 study in the journal Science also found that Denisovan DNA may have influenced modern human immune systems, as well as fat and blood sugar levels. Similarly, a 2024 study found that Papua New Guineans, who have been genetically isolated for 50,000 years, carry Denisovan genes that help their immune system.

However, some Denisovan genes may have harmful effects. A 2023 study found that DNA inherited from Denisovans may increase the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders, such as depression and schizophrenia. However, more research is needed to investigate this link.

Prior work found that Neanderthals also interbred with modern humans, with a 2013 Nature study estimating that the genomes of all non-Africans contain 1.5% to 2% Neanderthal DNA. In addition, a 2018 study in Nature revealed that the Denisovans and the Neanderthals also interbred with each other.

That 2018 Nature study examined a 1-inch-long (2.5 centimeters) bone fragment found in 2012 in Denisova Cave. This shard came from a long bone, such as a shinbone or a thigh bone. The thickness of the outer part of the bone suggested that it belonged to a female who was at least 13 years old when she died, while radiocarbon dating suggested that the fossil was more than 50,000 years old.

DNA from this fossil not only revealed that it was the first known Denisovan-Neanderthal hybrid but also that the Denisovan father of this individual had at least one Neanderthal ancestor, possibly as far back as 300 to 600 generations before his lifetime. All in all, this single discovery helped reveal multiple instances of interactions between the Neanderthals and the Denisovans.

In addition, the scientists found that the teenage girl's Neanderthal mother was genetically more similar to the Neanderthals of Western Europe than to a different Neanderthal that lived earlier in Denisova Cave. This finding suggests that Neanderthals migrated between Western and Eastern Eurasia for tens of thousands of years.

So far, scientists have sequenced the genomes of only six individuals from Denisova Cave. The finding that one of these six individuals had one Neanderthal parent and one Denisovan parent may suggest, from a statistical point of view, that interbreeding may have been common whenever these groups did interact, the researchers said.

Where did the Denisovans live?

As of 2025, scientists have unearthed Denisovan remains from sites in Siberia, China, Taiwan and Laos. These fossil data match with genetic evidence of Denisovans found in modern humans living in Melanesia.

Fossil evidence of the Denisovan jawbone from the Tibetan Plateau also revealed that this population of Denisovans was adapted to the high altitudes and cold climates.

When did the Denisovans live?

The Denisovans lived in Denisova Cave about 30,000 to 50,000 years ago, according to the 2010 Nature study that first uncovered the existence of Denisovans.

The oldest Denisovan fossils uncovered so far are about 200,000 years old, according to a 2021 study in Nature Ecology & Evolution. Those bones were also unearthed in Denisova Cave.

All in all, these findings suggest that the Denisovans were contemporaries of modern humans and Neanderthals, their closest relatives.

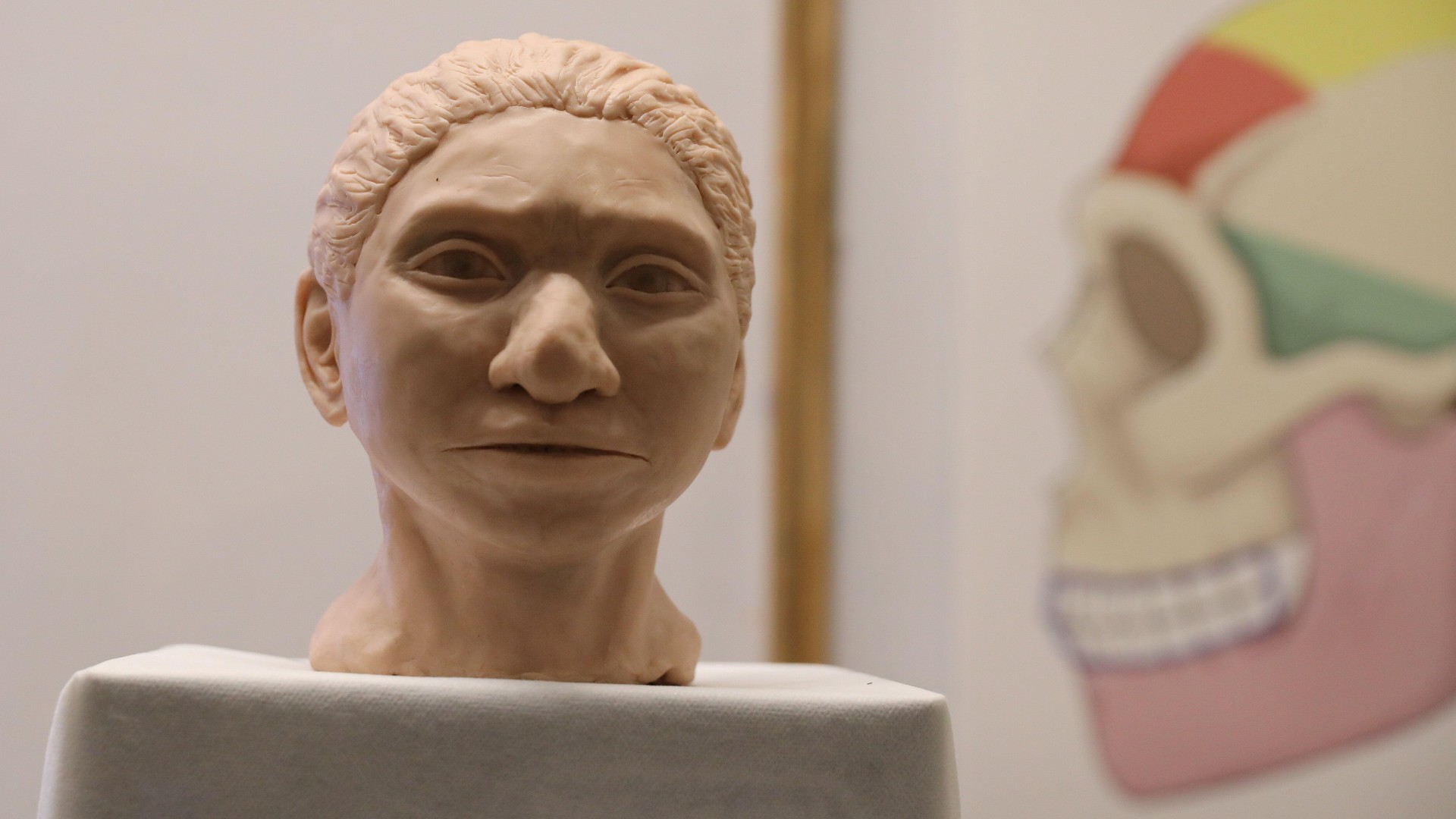

What did the Denisovans look like?

A 2019 study in the journal Science Advances describing a Denisovan finger bone suggested it came from an adolescent female about 13.5 years old, and another 2019 study in the journal Cell of that bone suggested she had dark skin, brown hair and brown eyes. The 2019 Cell study suggested that like Neanderthals, she may have had a low forehead, a protruding jaw and nearly no chin. However, Denisovans also may have had significantly longer dental arches (that is, their top and bottom rows of teeth jutted out farther) than those of Neanderthals and modern humans, and the tops of their skulls may have been noticeably wider.

Other than those differences, it remains difficult to know what the Denisovans looked like, because there are so few Denisovan fossils, Harvati said. "But, in general, I would expect that they would look more like Neanderthals rather than like us, as they are more closely related to each other than to us," she said.

For instance, "from their relatively close evolutionary relationship to the Neanderthals, we can guess that they were large-bodied and large-brained," Stringer said. Moreover, "we could expect that those populations living in relatively cold conditions — so not all of them — would have had bulky trunks and relatively short and wide bodies." Work is progressing on using Denisovan genomes to predict what they looked like, Stringer added.

Denisovan culture, tools and diet

In 2021, scientists unearthed the first stone tools linked with the Denisovans. These artifacts are associated with the oldest Denisovan fossils unearthed to date, according to the study in Nature Ecology & Evolution that detailed the find.

In the study, researchers examined 3,791 bone scraps from Denisova Cave. They looked for proteins they knew were Denisovan based on previous DNA research on the extinct lineage.

The scientists discovered three Denisovan bones. Based on the layer of earth in which the fossils were uncovered, the team determined that the fossils were about 200,000 years old. This layer also contained a trove of stone artifacts and animal remains, which may serve as vital archaeological clues about Denisovan life and behavior. Previously, Denisovan fossils were found only in layers without such archaeological material, or in layers that also might have contained Neanderthal material.

The findings suggested that these Denisovans' bones came from a time when, according to prior work, the climate was warm and comparable to today's, in a site favorable to human life that included broad-leaved forests and open steppe. Butchered and burnt animal remains found in the cave suggest the Denisovans may have fed on deer, gazelles, horses, bison and woolly rhinoceroses.

The stone artifacts found in the same layer as these Denisovan fossils are mostly scraping tools, which were perhaps used for treating animal skins. The raw material for these items likely came from river sediment right outside the entrance to the cave, and the river served as a water source that likely attracted prey.

The stone tools linked with these fossils have no direct counterparts in North or Central Asia. However, they do bear some resemblance to items found in Israel dating to between 250,000 and 400,000 years ago — a period linked with major shifts in human technology, such as the routine use of fire, the study's authors noted.

The 2024 study that revealed the Denisovan rib fragment found that these archaic humans butchered and ate a multitude of blue sheep — a goat species, also known as bharal, that still lives in the Himalayas today. According to butcher marks found on ancient bones in the area, the Denisovans also ate other animals, such as yaks, spotted hyenas, wolves, Tibetan foxes, snow leopards, golden eagles and common pheasant.

The Denisovans likely butchered these animals for their meat, marrow, hide and bones, which could be fashioned into tools, the study authors wrote.

"This reveals that Denisovans made full use of the animal resources available to them in order to survive on the high-altitude Tibetan Plateau during the last glacial–interglacial–glacial cycle," the team wrote in the study.

Why did the Denisovans go extinct?

It remains uncertain why and how the Denisovans went extinct. An overlap with expanding H. sapiens populations between 40,000 and 50,000 years ago, and a consequent competition for resources, was likely one reason the Denisovans went extinct, Stringer said. They also may have been absorbed into the gene pool of our species, he added. "But this is a wide open question," Harvati said.

Discover more

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

- Laura GeggelEditor

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.