Diamonds: Formation, grading and other facts

The science of diamonds: what they are, where they come from and why they are so special

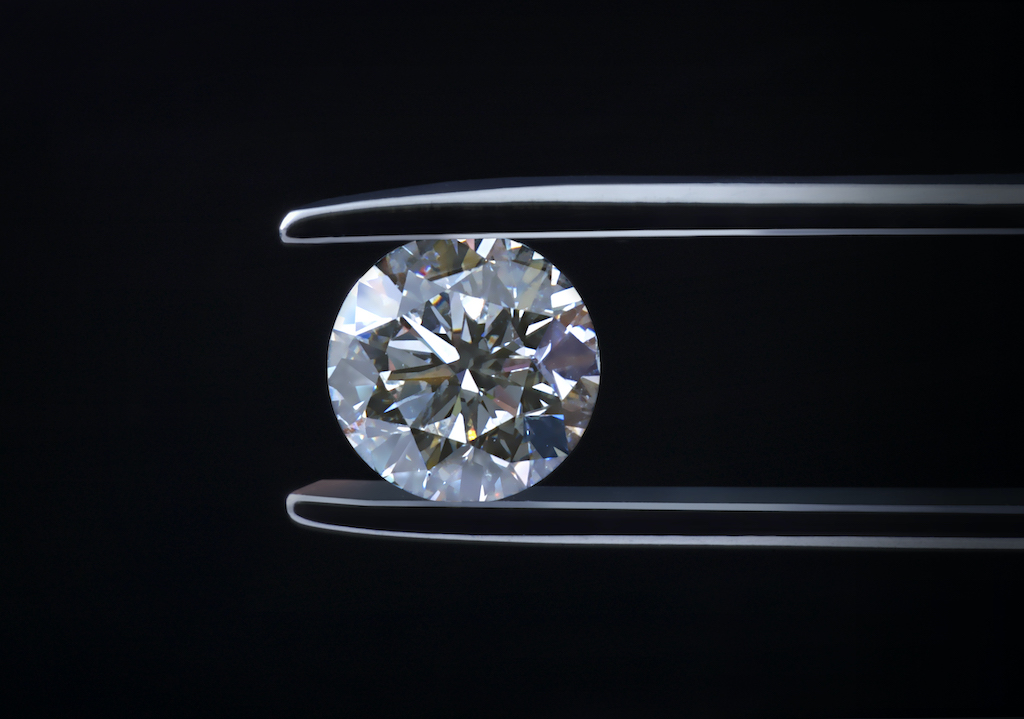

Diamonds are the most sought-after and admired gemstones, with a sparkling brilliance that sets them apart from all other jewelry. That’s as true today, when diamonds are mined on an industrial scale, as it was thousands of years ago when they were a much rarer commodity.

According to the Gemological Institute of America (GIA), the Roman historian Pliny wrote in the first century AD, “Diamond is the most valuable, not only of precious stones, but of all things in this world” . So where do diamonds come from, and what makes them so special?

Diamonds were first discovered in around 2500 BCE in India, according to the Cape Town Diamond Museum.. These diamonds weren’t mined in the modern sense – they were simply collected from the sediment in rivers and streams.

Their striking appearance made them highly desirable, and by the 4th century BC they were being traded with other parts of the world. Their extreme rarity meant that only the very wealthiest could afford them, and diamonds became the ultimate status symbol among the medieval elite. It was only in the 19th century, when more extensive diamond deposits were found in South Africa, that they became accessible to the general public, according to the museum.

What diamonds are made of

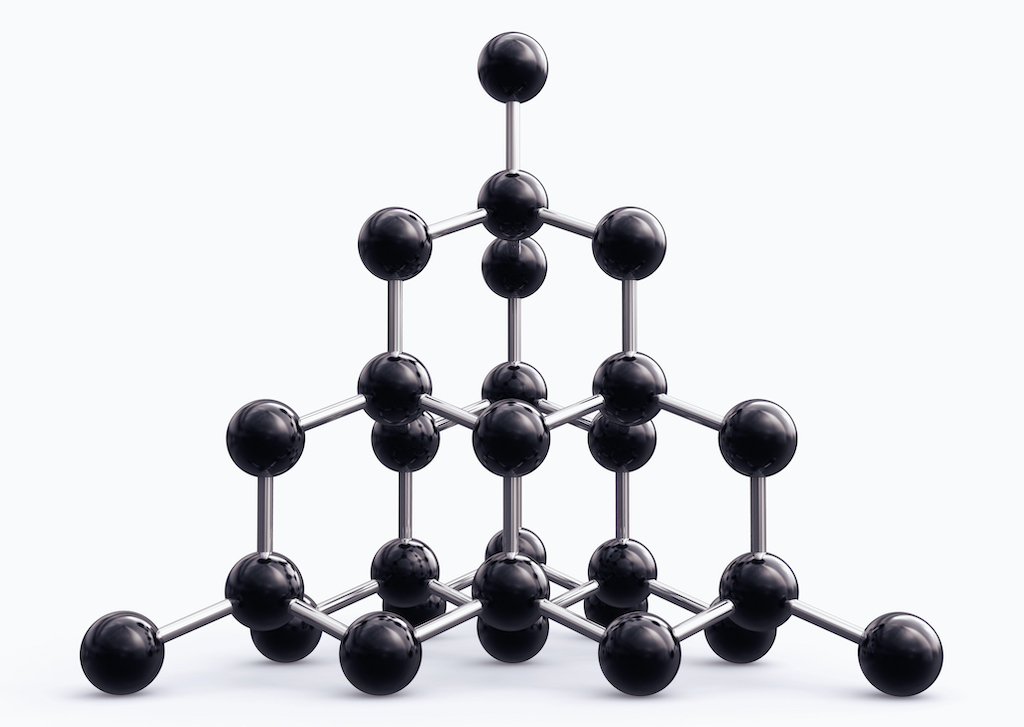

Diamond crystals are made from just one chemical element, carbon according to the GIA. The same is true of graphite, which is a much commoner mineral that couldn’t be more different in appearance and properties.

Graphite is what pencil lead is made from, and it’s so soft that it rubs off onto the page when you write with it. Diamond, on the other hand, is one of the hardest known substances – so hard it can only be scratched with another diamond. The difference lies in the arrangement of carbon atoms.

In graphite they form planar sheets, which can easily glide against each other, while in diamond they form a rigid three-dimensional structure,according to the Atlantic . The hardness of diamond means it has other, more practical, uses besides jewelry, particularly for technological uses such as cutting, and drilling, according to an article published in the 14th International Congress for Applied Mineralogy (ICAM2019).

How diamonds are formed

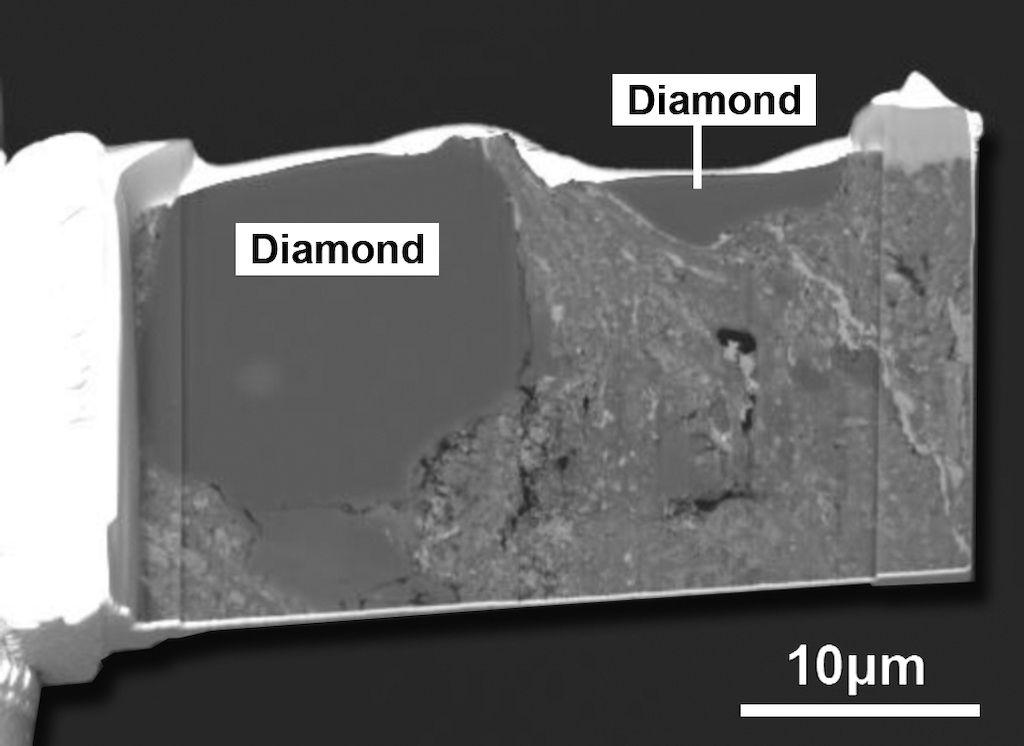

While carbon normally exists as graphite on the Earth’s surface, it can form diamond at much greater depths – a hundred miles or more – where temperatures and pressures are far higher, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

In a few places diamond-bearing material from these depths has been carried up to the surface by volcanic eruptions – and some of this material was subsequently washed into the river beds where diamonds were first found. Today, however, most diamonds come from directly mining the diamond-bearing rock, which is called kimberlite after the mining town of Kimberley in South Africa where it was first found.

How diamonds form in kimberlite pipes

Diamonds form deep inside the Earth, but they can reach the surface through volcanic pipes.

How diamonds are graded

Not all diamonds are the same. Some aren’t suitable for use in jewelry, and find their way into industrial applications. Even gem-quality diamonds vary considerably, and are typically graded according to the “4 Cs” of cut, color, clarity and carat according to the American Gem Society. The first three are self-explanatory, while “carat” is a measure of weight equivalent to 200 milligrams.

Why diamonds are expensive

At one time diamonds were expensive because of their rarity, but today they’re actually less scarce than many other gemstones, such as rubies or sapphires, according to the International Gem Society. However, diamond production involves a costly processing chain all the way from mining to polishing. On top of that, there’s a huge worldwide demand for diamonds, due to their widespread use in engagement rings – a “tradition” which originated in a clever marketing campaign in the 1930s, according to the BBC.

When James Bond creator Ian Fleming wrote Diamonds Are Forever in 1956, he might have been quoting an age-old proverb. But it turns out this too was a marketing slogan that had been coined less than a decade earlier. And it’s not even true, because diamond is an unstable form of carbon that eventually degrades to graphite – although it takes millions of years to do so, according to Dr Christopher S. Baird of West Texas A&M University.

How diamonds reflect light

Where diamonds are found

Historically, the epicentre of diamond mining activity was in Africa, but more recently diamonds have been found in many other parts of the world according to geologist Hobart M. King of Geology.com.

Africa still plays a leading role, with countries such as Botswana, Angola, South Africa, Namibia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo all producing more than a million carats of diamonds each year. However, the combined output of those five countries – around 30 million carats – is exceeded by two non-African countries, Russia and Canada, which produce 41 million carats between them. And many other countries produce smaller quantities of gem-quality diamonds, including Australia, Brazil and Guyana.

Diamonds in the sky

Although we think of diamonds as being very rare, the conditions which produce them occur quite widely throughout the universe. As a result, there really are “diamonds in the sky”. We have direct evidence of this in the form of diamond-containing meteorites, which originated very early in the history of the solar system, according to Space.com.

Fast-forwarding to the present day, Earth isn’t the only planet in the solar system where diamonds can be found. Deep inside the atmospheres of the ice giants Neptune and Uranus, carbon can be compressed to the extreme pressures and temperatures needed to form diamonds, according to Space.com. These then sink down to the planetary cores in the form of a spectacular "diamond rain".

Looking beyond the solar system, it may be possible to find planets with many more diamonds than the Earth. It’s conjectured that planets orbiting carbon-rich stars would have a much higher diamond content than our own planet.

A few years ago there was a flurry of excitement around one particular exoplanet, 55 Cancri e, which was hailed as the “diamond planet” because it was believed to be especially rich in diamonds, Space.com reported. However, while that theory hasn’t been completely disproved, it seems much less likely now.

Lab-grown diamonds

There’s nothing mystical or supernatural about diamonds – they’re simply the form that carbon takes under certain conditions of temperature and pressure.

Natural diamonds were formed where these conditions exist inside the Earth, but it’s also possible to create the necessary conditions artificially. This has been done on a commercial scale to make synthetic diamonds since the 1950s, according to materials engineer Dr Dmitri Kopeliovich.. One approach, called the high pressure, high temperature (HPHT) technique, attempts to mimic the natural process as closely as possible.

An alternative, called chemical vapour deposition (CVD), requires less extreme temperatures and pressures. At first synthetic diamonds were poor in quality, and only suitable for industrial purposes, but today they can be made attractive enough to use in jewelry, according to the Gemological Institute of America.

Additional resources

To learn more about diamond cutting and polishing, you can follow the step-by-step process on the Cape Town Diamond Museum website. Or find out about how the most colorful gemstones on Earth form in this TED Talk.

Bibliography

"Impact Diamonds: Types, Properties and Uses". 14th International Congress for Applied Mineralogy (2019). https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-22974-0_41

"On the Origin of Natural Diamonds". American Astronomical Society. https://adsabs.harvard.edu/pdf/1961ApJ...134..995W

"The ice layer in Uranus and Neptune– diamonds in the sky?" Nature (1981). https://www.nature.com/articles/292435a0

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Andrew May holds a Ph.D. in astrophysics from Manchester University, U.K. For 30 years, he worked in the academic, government and private sectors, before becoming a science writer where he has written for Fortean Times, How It Works, All About Space, BBC Science Focus, among others. He has also written a selection of books including Cosmic Impact and Astrobiology: The Search for Life Elsewhere in the Universe, published by Icon Books.