Strange single-celled life-form has a truly bizarre genome

A single-celled creature known as a dinoflagellate may have one of the weirdest genomes on Earth, The Scientist reported.

Life can be categorized into three major domains: Bacteria, Archaea and Eukarya. The latter carry their DNA inside a nucleus, where they package the genetic material in compact structures called chromosomes.

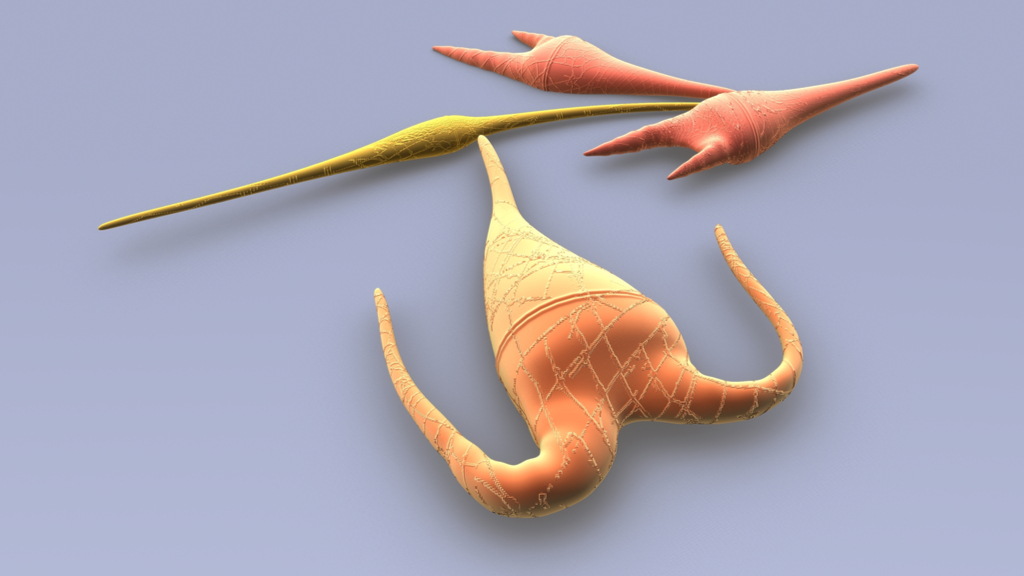

Dinoflagellates are eukaryotes, but unlike the chromosomes found in humans, which form an X shape, dinoflagellate chromosomes assemble in straight, rod-shaped structures, according to a new study, published April 29 in the journal Nature Genetics.

Genes line up in "blocks" along these rods, with each block oriented in the opposite direction of its neighbors; a block's orientation dictates which direction the cell can "read" the genetic instructions contained within each gene. This unusual, alternating structure both influences the overall shape of the chromosome and likely regulates how and when specific genes can be accessed, the team concluded.

Related: Prokaryotic vs. eukaryotic cells: What's the difference?

Dinoflagellates "don't fit with everything else we know about eukaryotes — how they structure their chromosomes, how they structure their genomes, how they regulate transcription," the process by which information in DNA gets copied down and sent out into the cell, study co-author Manuel Aranda, a functional geneticist at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia, told The Scientist.

The authors specifically studied the dinoflagellate Symbiodinium microadriaticum, a type of plankton that lives symbiotically with corals, and found that the species contains about 94 rod-shaped chromosomes. Genes within each rod likely cluster near other genes that have similar functions or interact with the same molecular pathways, the team concluded.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Furthermore, the team found that pairs of neighboring blocks tend to interact with each other, while faraway blocks rarely do so. A similar study by researchers from Stanford University, published April 29 in the journal Nature Genetics, found a similar pattern in the related dinoflagellate Breviolum minutum.

While both neighboring blocks "untwist" during transcription, granting access to their genetic material, blocks outside of that pair remain rigid and unchanged, Aranda and his team found. This finding hints that some kind of barrier exists between the different block pairs and that the barrier "must be something really important in organizing the chromosome … [and] may be important in regulating gene expression," Senjie Lin, a phytoplankton ecologist at the University of Connecticut who was not involved in the study, told The Scientist.

In general, other eukaryotes rely on histones — spool-like proteins that DNA winds around, like thread — to wind and unwind during transcription, The Scientist reported. But dinoflagellates produce very few histones, and based on the new study, they may instead use these mysterious barriers to maintain their chromosomal structure and control transcription.

Many questions about dinoflagellate genomes remain to be answered; read all about them in The Scientist.

Originally published on Live Science.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.