Bizarre tail on little dinosaur-age bird was literally a drag

Its tail was over 150% the length of its body.

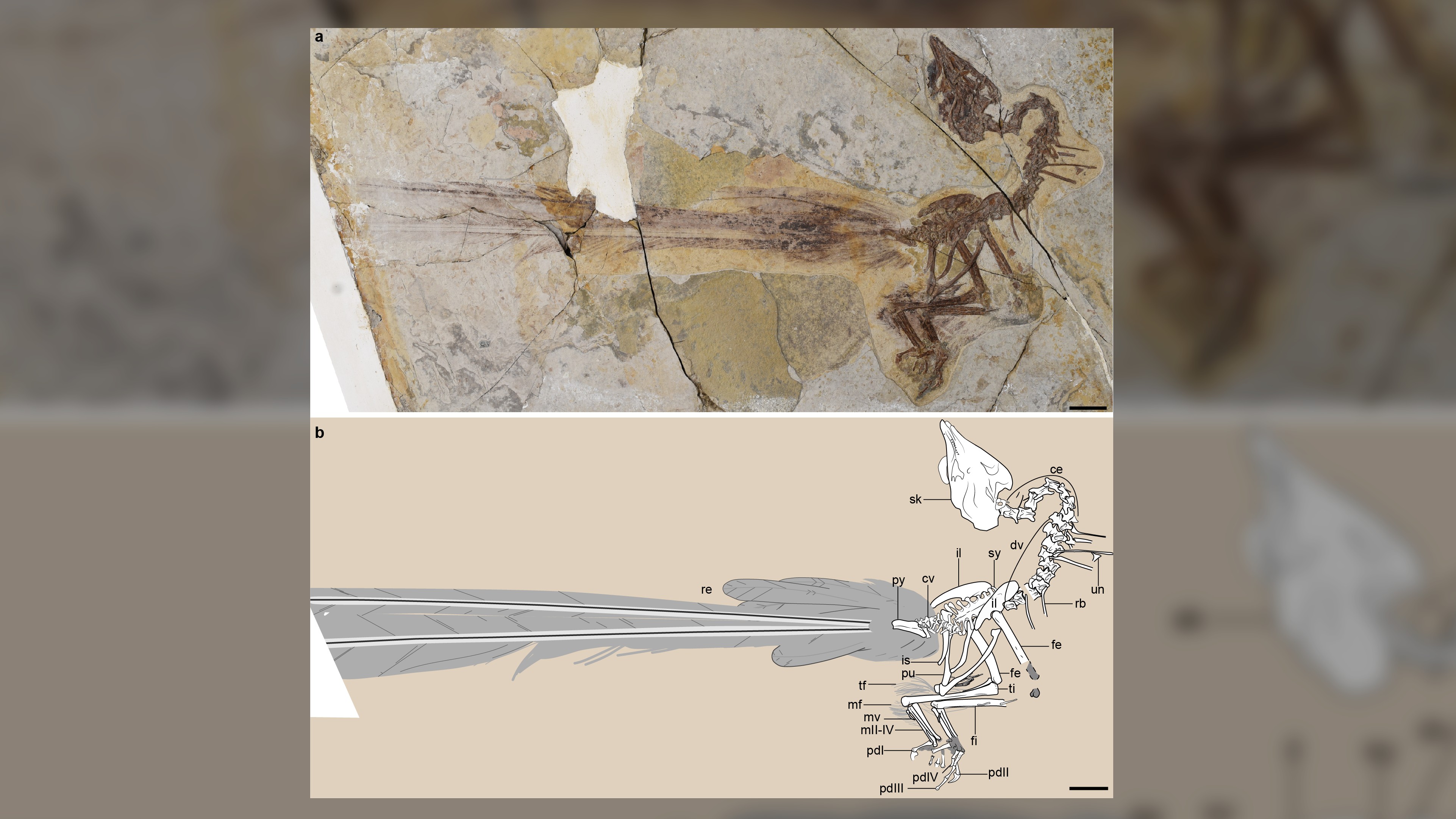

A dinosaur-age bird's extravagant tail feathers may have helped it win over mates, but the fluffy rump was also literally a drag during flight, a study of a well-preserved fossil finds.

The bird's tail is truly "bizarre," the researchers said; it had two lengthy plume feathers that were more than 150% of its body length. At the tail's base, a stiff fan of short feathers likely helped the bird fly, the researchers said.

"We've never seen this combination of different kinds of tail feathers before in a fossil bird," study co-researcher Jingmai O'Connor, a paleontologist at the Field Museum in Chicago, said in a statement.

Related: Photos: Dinosaur-era bird sported ribbon-like feathers

The 120-million-year-old fossil was unearthed in the Jehol Biota in northeastern China, an area well known for its early Cretaceous period fossils, which were preserved in volcanic sediments. Researchers named the bird Yuanchuavis kompsosoura, after the Mandarin word "yuanchu," which refers to a Chinese mythological bird, and "avis," the Latin word for bird. The species name means "elegant tail" in Greek.

The unique combination of a short tail fan and two long feathers, known as a pintail, is seen in some modern birds, such as sunbirds and quetzals. However, scientists have never found a fossil bird or nonavian dinosaur with that combination, O'Connor said.

Y. kompsosoura is a member of the enantiornithes, an ancient group of birds that went extinct along with the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. Other enantiornithes had either plumes or tail fans, but not both, said study first author Min Wang, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. "The tail fan is aerodynamically functional, whereas the elongated central paired plumes are used for display, which together reflect the interplay between natural selection and sexual selection," Wang said in the statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In effect, the toothed, blue-jay-size Y. kompsosoura would have been able to fly well, but its sexy tail plumes would have been a literal drag and even likely attracted unwanted attention from predators.

"Scientists call a trait like a big fancy tail an 'honest signal,' because it is detrimental, so if an animal with it is able to survive with that handicap, that's a sign that it's really fit," O'Connor said. "A female bird would look at a male with goofily burdensome tail feathers and think, 'Dang, if he's able to survive even with such a ridiculous tail, he must have really good genes.'"

Usually, birds with flamboyant tail feathers don't live in places that require adroit flight. "Birds that live in harsher environments that need to be able to fly really well, like seabirds in their open environment, tend to have short tails," O'Connor said. "Birds with elaborate tails that are less specialized for flight tend to live in dense, resource-rich environments, like forests."

Moreover, Y. kompsosoura's tail hints that the males were likely absentee fathers. Often, predators are more likely to notice birds with flashy feathers, so it's usually the duller-colored female bird that cares for the young, O'Connor noted. In addition, it takes a lot of work to care for long feathers, so these males probably couldn't invest resources in chick rearing, too.

The study was published online Thursday (Sept. 16) in the journal Current Biology.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.