The dinosaurs were likely doomed before the asteroid struck

Extinction rates were outpacing evolution of new species.

Dinosaurs were facing a crisis even before the asteroid hit, with extinctions outpacing the emergence of new species — a situation that made them "particularly prone to extinction," a new study suggests.

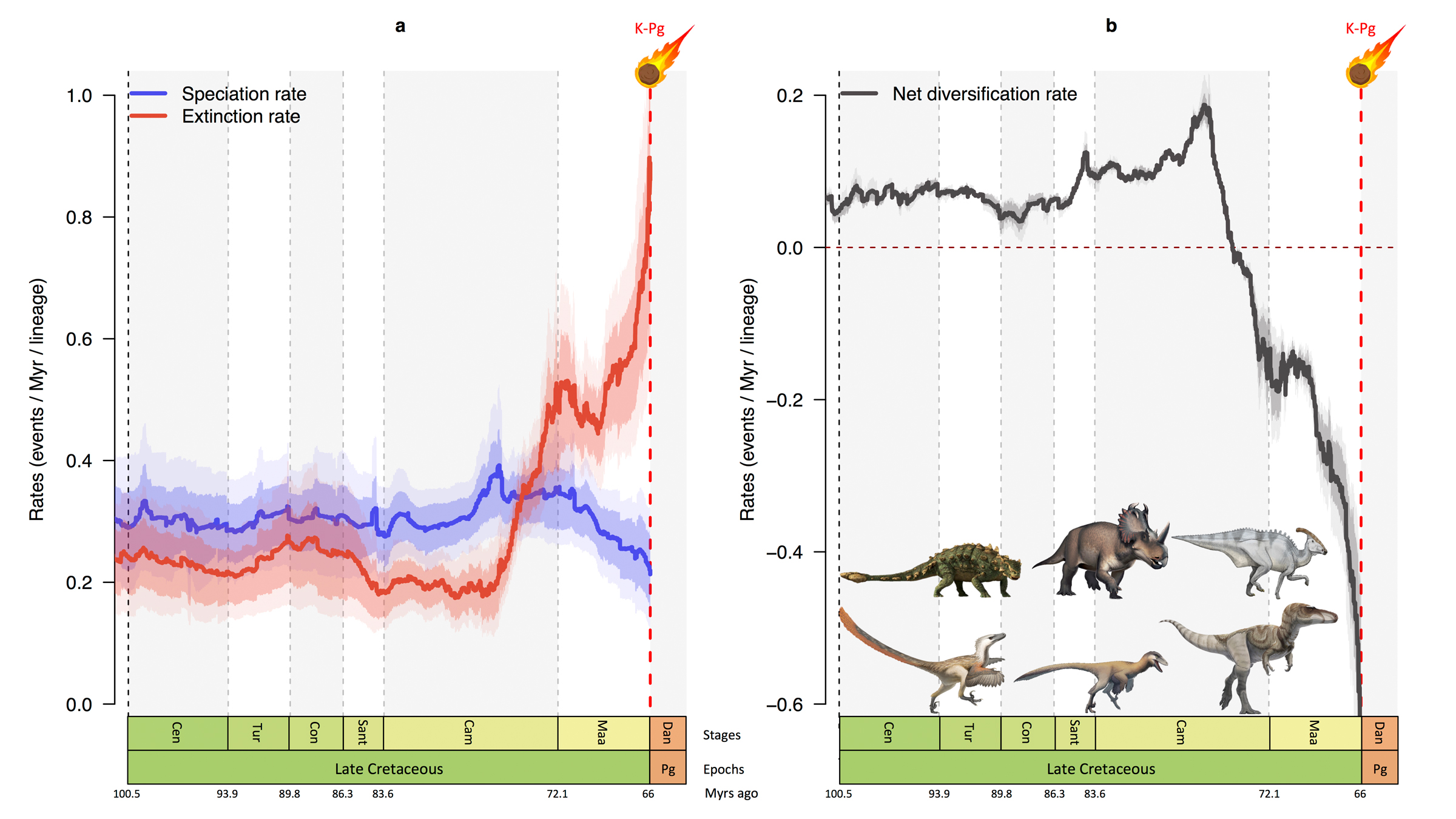

Researchers looked at the evolutionary trends of six major dinosaur groups, finding that both herbivorous and carnivorous dinosaurs were in decline for about 10 million years before the mass extinction 66 million years ago, at the end of the Cretaceous period.

"We find that the diversity of dinosaurs declined from 76 million years ago," study lead researcher Fabien Condamine, a research scientist at the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) and the Institute of Evolutionary Science of Montpellier in France, told Live Science in an email.

Related: Photos: See the armored dinosaur named for Zuul from 'Ghostbusters'

The new paper is the latest of a slew of studies tackling the question of whether dinosaurs were doing badly before the space rock hit and ultimately wiped them out. However, while the new research uses a new statistical modeling technique that limits problems tied to gaps in the fossil record, it still doesn't definitively answer the question, said David Černý, a doctoral candidate in the Department of the Geophysical Sciences at the University of Chicago. Černý wasn't involved with the new study, but he has done similar research on diversification rates in extinct animal groups.

"I have reservations about how much stock to put in these findings, especially for a group like dinosaurs, whose fossil record is rather limited compared to, say, North American mammals or marine invertebrates," Černý told Live Science in an email.

Eyes on extinction

To investigate, Condamine and his colleagues put together a list more than 1,600 dinosaur fossils, which comprised 247 late-Cretaceous dinosaur species from six families: the herbivorous ankylosaurs (armored dinosaurs), ceratopsians (horned dinosaurs, such as Triceratops) and hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs), as well as the carnivorous tyrannosaurs, troodontids (bird-like maniraptorans) and dromaeosaurids (bird-like dinosaurs). The scientists documented all fossil occurrences so they would know the approximate geologic age of appearance and disappearance for each species, he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, recovered fossils never tell the whole tale; the majority of dinosaurs never fossilized, and even for those that did, many specimens remain undiscovered. So the team accounted for these limitations when they modeled the diversity and extinction rates, Condamine said. "These models allow us to estimate the 'true' ages of appearance and extinction of each species, and by doing this for all species, we can then deduce diversity curves from their origin to their extinction," he said.

The models shed light on how many dinosaur species existed at different times over the last 40 million years of the dinosaur era, Condamine said. The results showed that the decline in diversity affected all six families, although some declined more than others. For instance, herbivore diversity declined sharply, especially among the ankylosaurs and ceratopsians, in the last 10 million years of the dinosaur age, while the troodontids showed "a very small decline," in the last 5 million years of that period, Condamine said.

The decline appears to be linked to an increased extinction rate in older species, the researchers said. Perhaps these species couldn't adapt to a changing climate; in addition, new "fit" species may not have been emerging at the time, they said.

Related: Photos: Spiky-headed dinosaur found in Utah, but it has Asian roots

Duck-billed dinosaurs may have been another culprit, at least among herbivorous dinosaurs. Every time a new hadrosaur species evolved, the extinction rate increased by 0.6% in ankylosaurs and by 9.1% in ceratopsians, the researchers found. Duck-billed dinosaur diversity also declined more slowly than it did in the other families. In other words, perhaps the duck-bills outcompeted some of their herbivorous cousins, the researchers suggested.

Why the decline?

Climatic cooling was probably a big driver in the dino decline, the researchers said. At the end of the Cretaceous period, there was a stupendous 12.6-degree Fahrenheit (7 degrees Celsus) drop in temperature in the North Atlantic. As the climate cooled, the herbivorous dinosaurs began to decline, and their plummeting numbers could have precipitated the carnivores' decline, given that carnivores preyed on herbivores, Condamine said.

"Herbivores are keystone species in ecosystems, and their disappearance leads to cascade extinctions," he said.

Moreover, it's possible that dinosaur sex was partially influenced by temperature, as it is in modern-day crocodiles and turtles, the researchers noted. If this was the case, "sex switching of embryos could have contributed to diversity loss with a cooling global climate at the end of the Cretaceous," the researchers wrote in the study.

"This cooling is directly involved in the increase of the extinction of dinosaurs 10 million years before the fall of the asteroid," Condamine said. "Indeed, dinosaurs were mesothermic [halfway between warm- and cold-blooded] organisms and therefore depended largely on the temperature of their environment for their activity."

However, "we must remain cautious about the conclusions, for several reasons," he noted. For one, not every dinosaur species was included in the study, "so it is possible that some groups are not in decline." Moreover, if new dinosaur species from the late Cretaceous were to be discovered in the fossil record, this could influence the results, he said.

Hold your horses

The new study is a "valuable contribution, but I don't think we've heard the last word on the subject yet," Černý said. While the methods in the new study have fewer caveats than earlier research aimed at answering the diversity question, the study still has a number of issues, he said. For instance, "it's hard to say for sure whether net diversification dropped because of increased extinction, decreased speciation or both," Černý said.

In addition, sometimes a sudden extinction event might appear "time smeared" and gradual, he said. "The better the fossil record gets, the less serious this problem becomes, but it's unclear if the dinosaur fossil record, even at its best, is good enough to avoid this issue entirely. The fact that the decline inferred by the new study is so close in time to the final extinction just makes this question all the more salient.

"Finally, we are also dealing with a long chain of inferences here, and if the first few links don't hold up — if the diversification rate estimates are not reliable, for example — this will cause further problems down the line," Černý added. "If we can't be confident about whether nonbird dinosaurs underwent a period of decline, then asking about the causes of that decline is clearly beside the point."

Other studies have also reported that large plant-eating dinosaurs, primarily in North America, declined toward the end of the Cretaceous, Steve Brusatte, a paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email.

"What it means is open to debate," Brusatte said. "This diversity decrease may well have made dinosaurs more susceptible to the sudden and unpredictable terror unleashed by the asteroid. But I doubt that this decline meant that dinosaurs were in any serious trouble or that they would have been doomed to extinction if the asteroid didn't hit."

The study was published online Tuesday (June 29) in the journal Nature Communications.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.