Origin of dinosaur-ending asteroid possibly found. And it's dark.

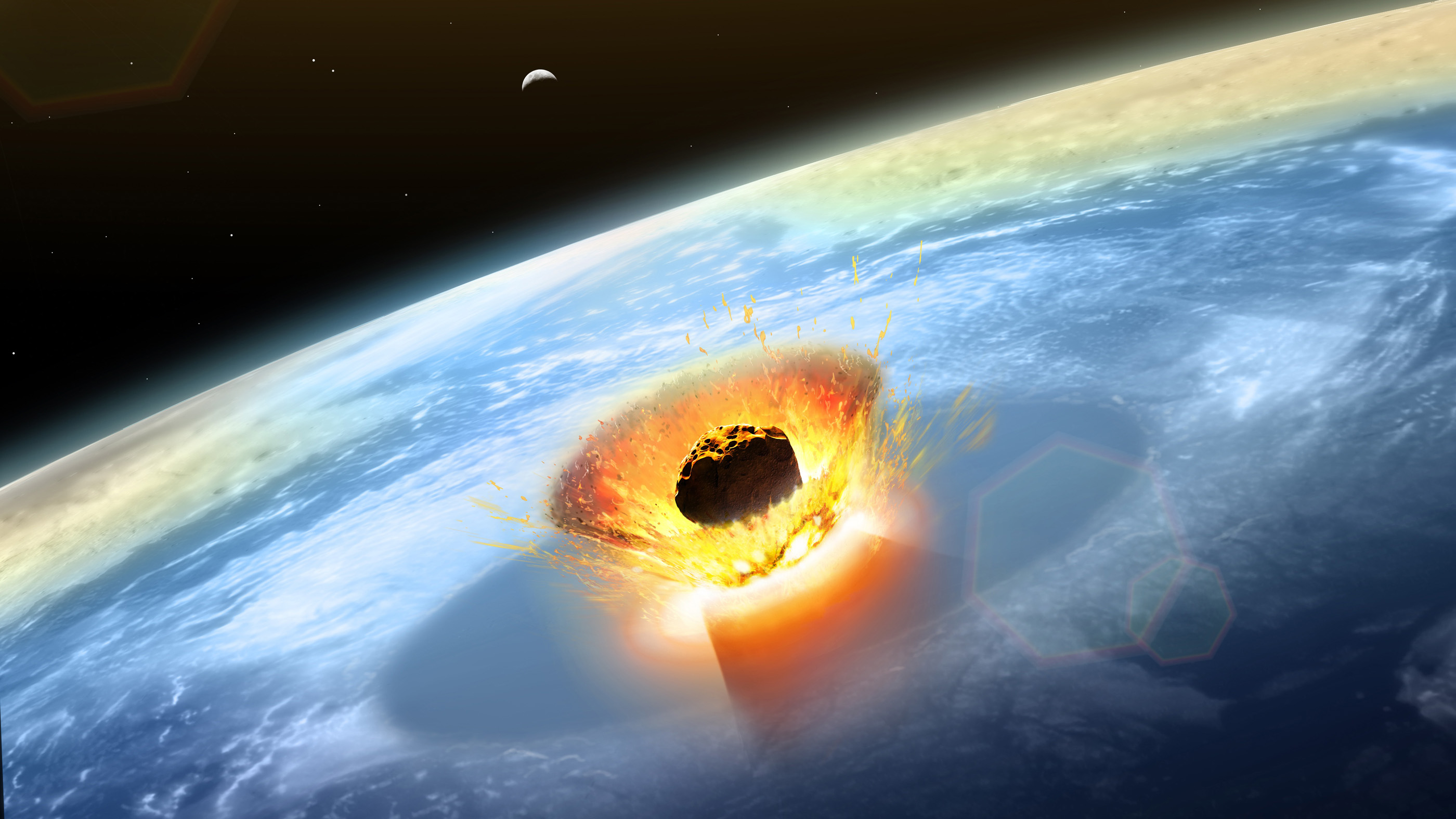

About 66 million years ago, an estimated 6-mile-wide (9.6 kilometers) object slammed into Earth, triggering a cataclysmic series of events that resulted in the demise of non-avian dinosaurs.

Now, scientists think they know where that object came from.

According to new research, the impact was caused by a giant dark primitive asteroid from the outer reaches of the solar system's main asteroid belt, situated between Mars and Jupiter. This region is home to many dark asteroids — space rocks with a chemical makeup that makes them appear darker (reflecting very little light) compared with other types of asteroids.

Related: The 5 mass extinction events that shaped the history of Earth

"I had a suspicion that the outer half of the asteroid belt — that's where the dark primitive

asteroids are — may be an important source of terrestrial impactors," said David Nesvorný, a researcher from the Southwest Research Institute in Colorado, who led the new study. "But I did not expect that the results [would] be so definitive," adding that this might not be true for smaller impactors.

Clues about the object that ended the reign of non-avian dinosaurs have previously been found buried in the Chicxulub crater, a 90-mile-wide (145 km) circular scar in Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula left by the object's collision. Geochemical analysis of the crater has suggested that the impacting object was part of a class of carbonaceous chondrites — a primitive group of meteorites that have a relatively high ratio of carbon and were likely made very early on in the solar system's history.

Based on this knowledge, scientists have previously tried to pinpoint the impactor's origin, but many theories have crumbled over time. Researchers have previously suggested the impactor came from a family of asteroids from the inner part of the main asteroid belt, but follow-up observations of those asteroids found they didn't have the right composition. Another study, this one published in February in the journal Scientific Reports, suggested the impact was caused by a long-period comet, Live Science reported. But that research has since come under criticism, according to a June paper published in the journal Astronomy & Geophysics.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the new study, published in the November 2021 issue of the journal Icarus, researchers developed a computer model to see how often main belt asteroids escape toward Earth and if such escapees could be responsible for the dinosaur-ending crash.

Simulating over hundreds of millions of years, the model showed thermal forces and gravitational tugs from planets periodically slingshotting large asteroids out of the belt. On average, an asteroid more than 6 miles wide from the outer edge of the belt was flung into a collision course with Earth once every 250 million years, the researchers found. This calculation makes such an event five times more common than previously thought and consistent with the Chicxulub crater created just 66 million years ago, which is the only known impact crater thought to have been produced by such a large asteroid in the last 250 million years. Furthermore, the model looked at the distribution of "dark" and "light" impactors in the asteroid belt and showed half of the expelled asteroids were the dark carbonaceous chondrites, which matches the type thought to have caused Chicxulub crater.

"This is just an excellent paper," said Jessica Noviello, NASA fellow in the postdoctoral management program at the Universities Space Research Association at Goddard Space Flight Center, who was not involved with the new research. "I think they make a good argument for why [the Chicxulub impactor] could have come from that part of the solar system."

In addition to possibly explaining the origin of the Chicxulub crater impactor, the findings also help scientists understand the origins of other asteroids that have struck Earth further in the past. Neither of the other two largest impact craters on Earth, the Vredefort crater in South Africa and the Sudbury Basin in Canada, have known impactor origins. The results could also help scientists predict where future large impactors might originate..

"We find in the study that some 60% of large terrestrial impactors come from the outer half of the asteroid belt ... and most asteroids in that zone are dark/primitive," Nesvorný told Live Science. "So there is a 60% — 3 in 5 — probability that the next one will come from the same region."

Originally published on Live Science.

Mara Johnson-Groh is a contributing writer for Live Science. She writes about everything under the sun, and even things beyond it, for a variety of publications including Discover, Science News, Scientific American, Eos and more, and is also a science writer for NASA. Mara has a bachelor's degree in physics and Scandinavian studies from Gustavus Adolphus College in Minnesota and a master's degree in astronomy from the University of Victoria in Canada.