Achoo! Respiratory illness gave young 'Dolly' the dinosaur flu-like symptoms

The young sauropod's illness was a real pain in the neck.

Hacking coughs, uncontrollable sneezing, high fevers and pounding headaches can make anyone miserable — even a dinosaur.

Recently, researchers identified the first evidence of respiratory illness in a long-necked, herbivorous type of dinosaur known as a sauropod, which lived about 150 million years ago during the Jurassic period (201.3 million to 145 million years ago) in what is now Montana.

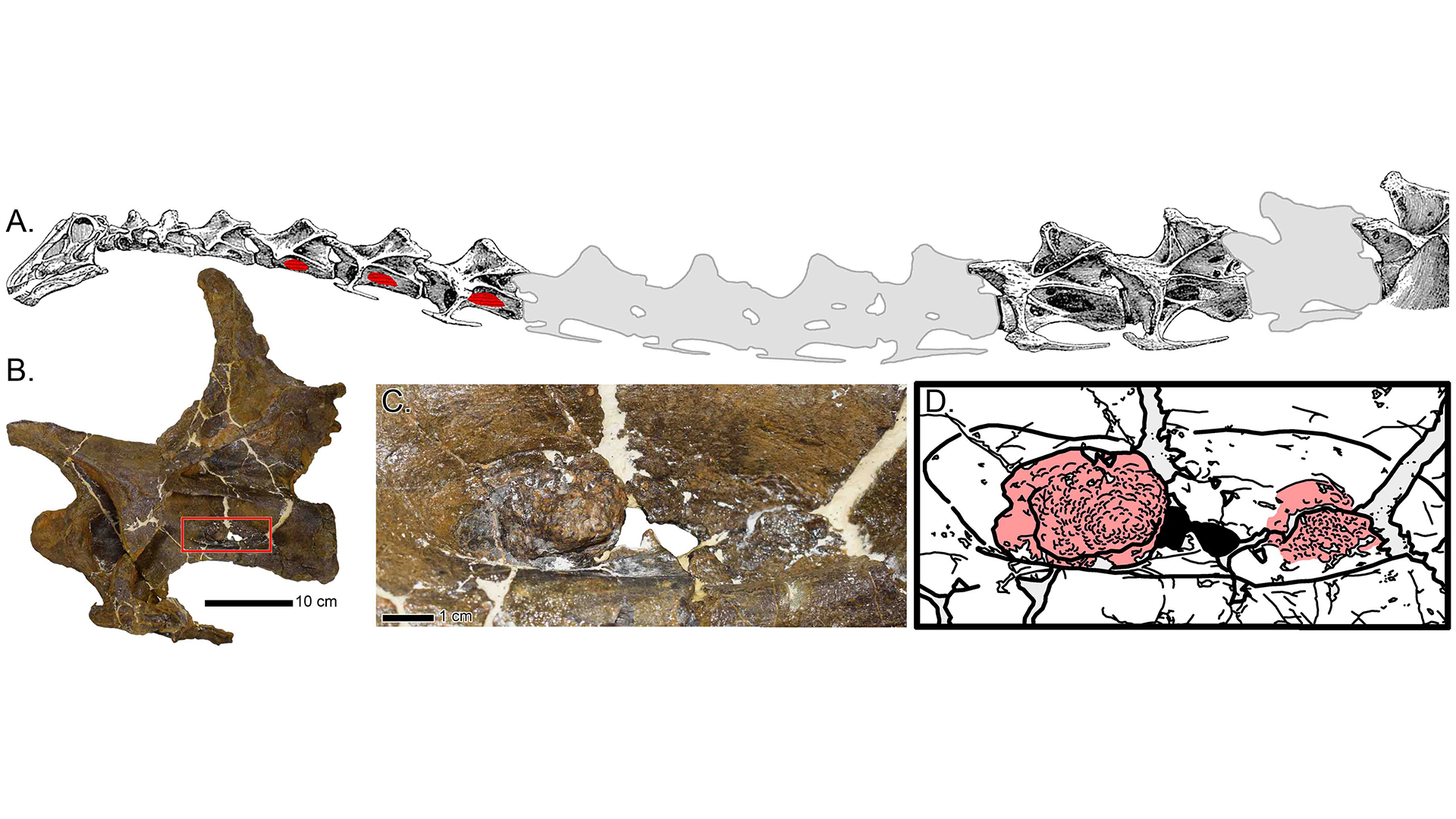

The fossil, nicknamed "Dolly," contained misshapen structures in the neck bones. Those vertebrae were once paired with air sacs that connected to the lungs and were part of the sauropod's respiratory system, and the bones' abnormal appearance was likely caused by a raging respiratory infection that may have led to the animal's death when it was 15 to 20 years old, researchers found.

Related: 7 surprising dinosaur facts

While paleontologists don't know what type of microorganism sickened the sauropod, the dinosaur likely experienced flu-like symptoms resembling those that affect modern birds (and people) with severe respiratory illness, according to a study published Feb. 10 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Paleontologists found the fossil — a skull and partial neck — near Bozeman, Montana, in 1990. After wrapping it in a protective plaster jacket, they brought it to the nearby Museum of the Rockies. The fossil, now known as MOR 7029, remained unexamined in storage at the museum for more than a decade, said lead study author Cary Woodruff, director of paleontology at the Great Plains Dinosaur Museum in Malta, Montana.

Woodruff began studying Dolly in the mid-2000s as a master's candidate at the Museum of the Rockies, and he realized that the fossil was from an undescribed species in the Diplodocus family Diplodocidae (Dolly's unofficial nickname starts with the same letter as "diplodocus," and is also a nod to country singer/songwriter Dolly Parton, Woodruff told Live Science.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

He went back to the site where Dolly was originally excavated, to see if there were any more bones to be found, and it took until 2018 for Woodruff to collect all of the available material and examine it together. Early in his investigation, "these pathologic structures in the vertebrae just absolutely popped out," and the bone anomalies were unlike anything that he or any sauropod expert had ever seen, he said.

Broccoli bones

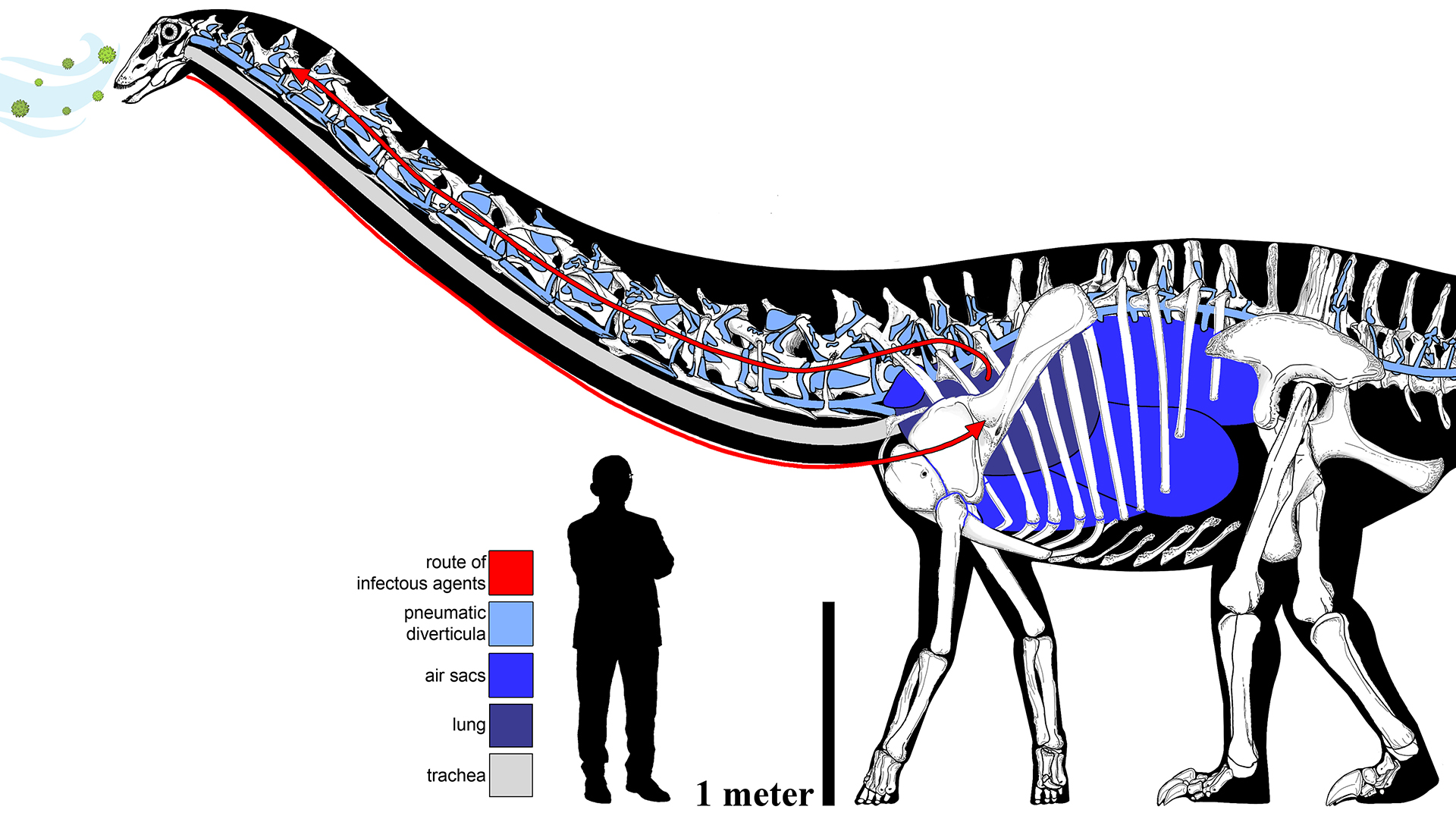

The respiratory systems of sauropods, like those of their modern bird relatives, differed from mammals', with networks of air sacs that linked to their lungs and performed like a bellows, circulating oxygen during both exhalation and inhalation, according to the study. In sauropods, respiratory tissue was connected to neck vertebrae around large holes in the sides of the bones, known as pleurocoels (PLOO'-roh-seels).

Pleurocoel tissue is usually very smooth — almost glass-like. But in three of Dolly's vertebrae, computed X-ray tomography (CT) scans revealed that the pleurocoel boundaries were irregular and rough, with bumpy protrusions "like the head of a broccoli floret," Woodruff said.

"The fact that we had these weird structures at that junction where the respiratory hose connects into the vertebrae — that was a really good point in cuing us to the fact that this might be respiratory-related," he said. An infection that caused airsacculitis — inflammation or infection of the air sacs — could have then spread into the bone and produced the lesions that were preserved in the fossils, the study authors reported.

A fungus among us

Respiratory infections can be caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites. To narrow down what may have triggered Dolly's respiratory distress, the study authors compared the fossils' scars to lesions from respiratory ailments in modern birds, which are a living lineage of dinosaurs. (Sauropods occupy a different branch of the dinosaur family tree, and are one type of nonavian dinosaur.) The researchers also considered respiratory disorders that affect modern reptiles, which are distantly related to dinosaurs.

They identified a fungal respiratory disease that affects both reptiles and birds: aspergillosis, caused by the mold Aspergillus and the most common cause of respiratory illness in modern birds. If the most common respiratory disorder in a living dinosaur is a fungal infection, "it gives support to the fact that a dinosaur in the past could have also been susceptible to fungal disease as well," Woodruff told Live Science.

Birds with respiratory illness exhibit many of the same symptoms caused by flu and pneumonia in people, including sneezing, coughing, headache, fever, diarrhea and weight loss, which makes it all too easy to imagine how miserable a sick dinosaur might have felt millions of years ago, Woodruff said.

"You can hold that fossil of Dolly in your hand and know that 150 million years ago, that dinosaur was feeling as crummy when it was sick as you do when you're sick," he said. "I personally don't know of any fossil I've interacted with where I've been able to empathize and feel for the animal as much."

Was Dolly's disease severe enough to be deadly? While it's impossible to say for sure, aspergillosis in modern birds can be lethal if untreated, and being sick may have lowered the dinosaur's chances of survival even more, the study authors reported. In herd animals such as sauropods, sick individuals may self-isolate from the group or may lag behind when the herd is traveling, which can make them easy targets for predators — especially when the animals are already weakened by illness.

"Regardless of exactly how death occurred, I think that this disease definitely contributed to the death of the animal in one way or another," Woodruff said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.