Did all roads lead to Rome?

Yes, no. Maybe so.

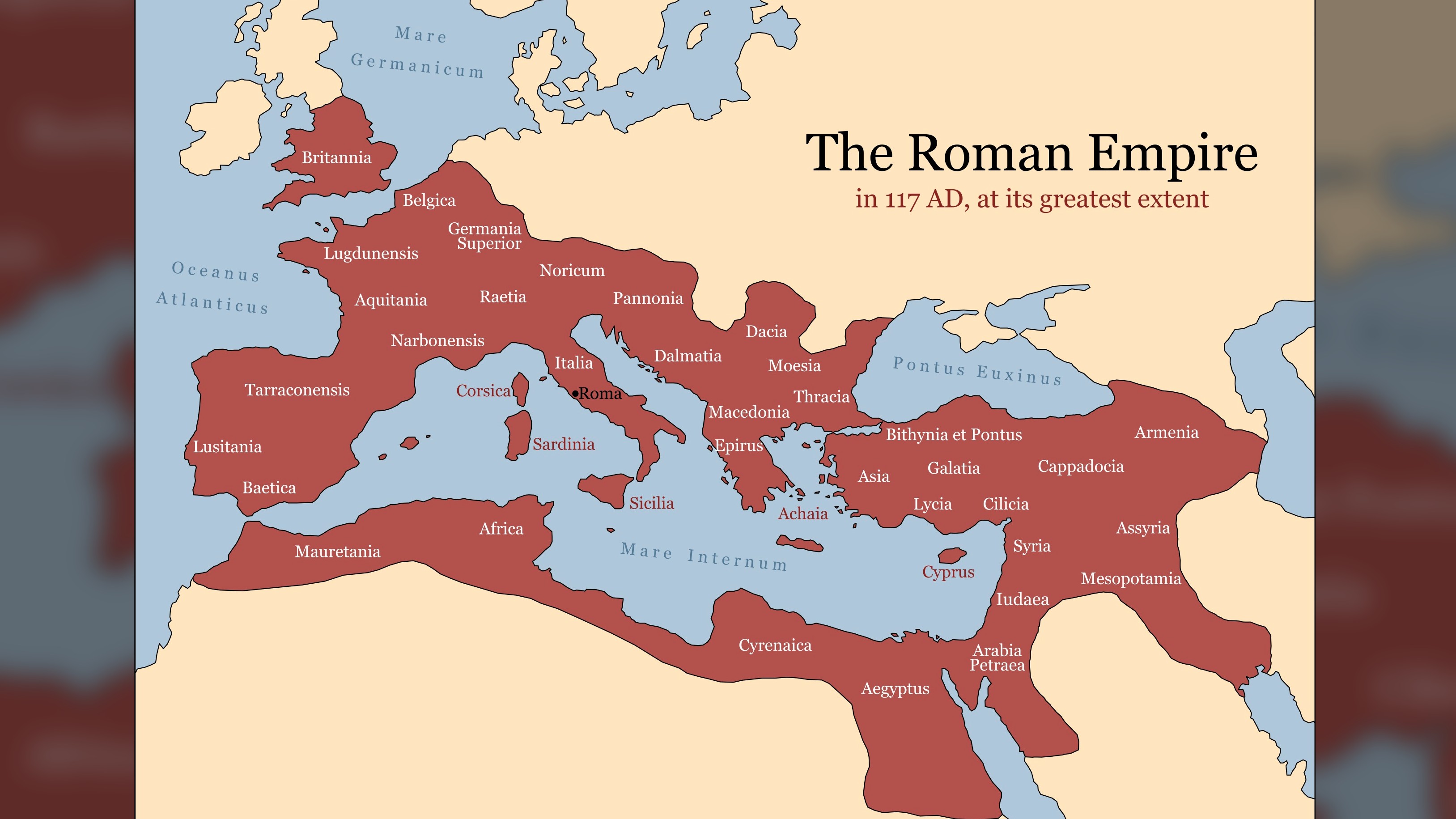

At the zenith of its control, the Roman Empire had a road network stretching from the sun-bathed Rock of Gibraltar to the marshlands of Mesopotamia. As the saying goes, "All roads lead to Rome" — but was that really the case?

The answer is not as easy as an unequivocal 'yes' or 'no.' It's a little more complicated than that.

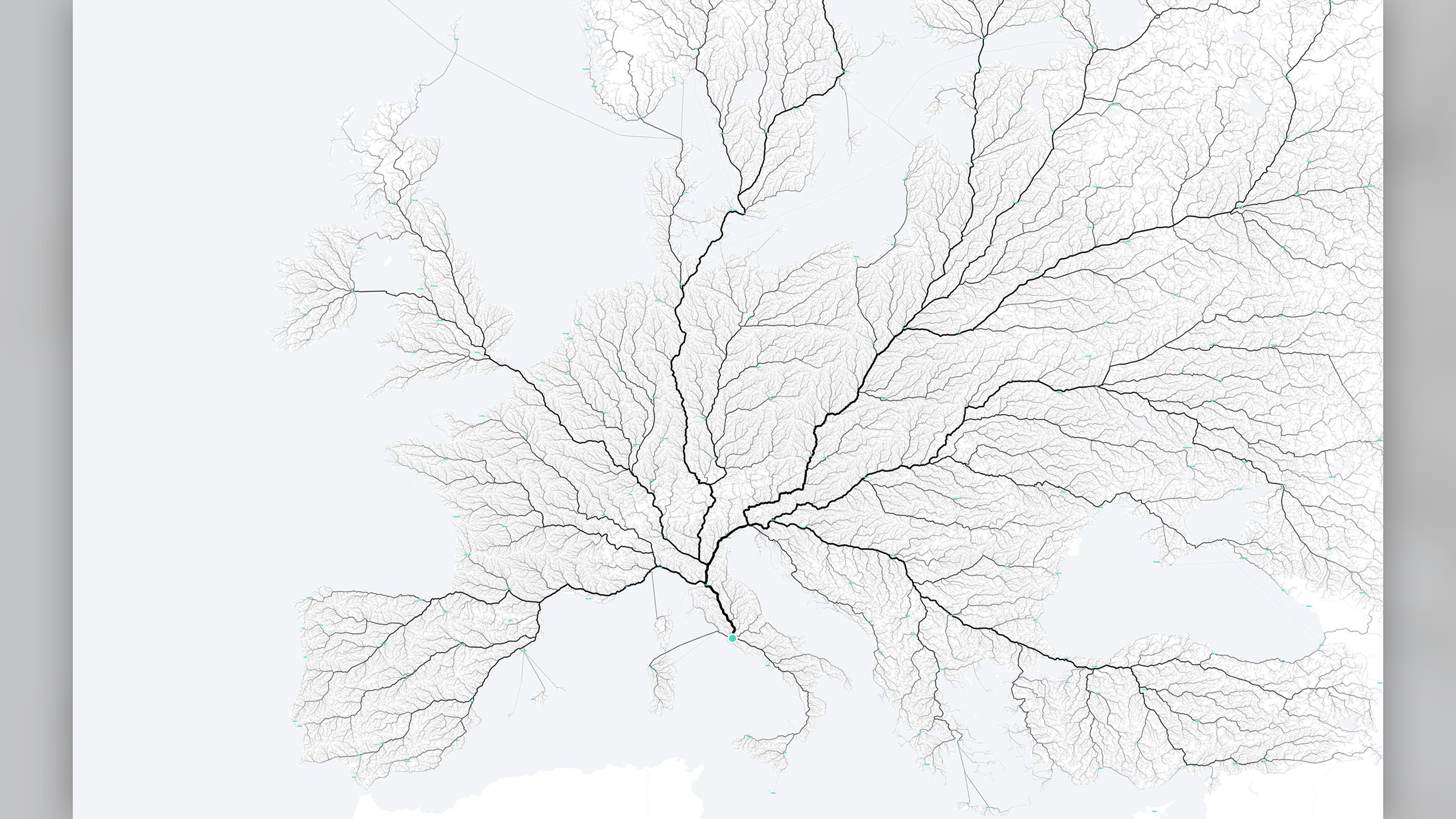

In 2015, three researchers at the Moovel Lab — a now-defunct German urban design team — dropped a uniform grid of almost 500,000 points across a map of Europe. These points didn't represent ancient or modern cities, but were simply random spots from which to start a journey to the imperial capital. The team then used an algorithm to calculate the best route to Rome using modern routes from each of those starting points. The more frequently a segment of a road was used across the different points, the bolder it was drawn on the map. Their results showed a mesmerizing web of roads that led to Rome, connecting other major cities along the way, such as London, Constantinople (present-day Istanbul) and Paris, which were also part of the ancient empire.

Related: Why did Rome fall?

News of the map went viral, but it didn't actually prove that all roads lead to Rome. If the researchers had conducted the same exercise, but instead looked at the quickest way from those same 500,000 points to Berlin or Moscow, the map would show a similarly vast array of roads leading to those cities. "Our project didn't really answer the question whether all roads lead to Rome," said Philipp Schmitt, one of the designers behind the artwork. "It was a 99% playful exploration of the question."

Yet Schmitt's design still tells us something about the endurance of Roman roads: A lot of Europe's road infrastructure is still designed to link major cities to the Italian capital, potentially a legacy of the empire. Other researchers have also found this to be the case.

"We've used computer modeling to look at the most likely or most logical routes that connect two points on the landscape, and then compared that with our knowledge of Roman roads to see if they're similar," said César Parcero-Oubiña, a landscape archaeologist at the Institute of Heritage Sciences in Madrid, Spain. "Modern routes are often the same in most cases if you're going to and coming from places that were both also Roman cities."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In other words, many of Europe's multi-lane highways are the successors of Roman roads. This has changed in recent years, however, Parcero-Oubiña told Live Science. "Newly built motorways avoid populated places to save money in acquiring land, so that means some brand new motorways weren't always as logical as the old Roman routes."

And that brings us to the question at hand: What was the Roman logic for road building? Did all roads lead to Rome? "It depends on the importance of the road," Parcero-Oubiña said. "The logic of how an ancient empire works isn't so different to a modern country. The Romans weren't that different to us; they were just trying to minimize routes to save time."

The main roads were straight lines whenever geography allowed, and they connected important cities to other important cities, Parcero-Oubiña said. These direct routes were only possible once a country had been properly annexed by the Romans and any military opposition subdued, otherwise it wouldn't have been safe enough to travel in the open. In the early days following the acquisition of a province when barbarians, or non-Romans, were still resisting occupation, the Romans would stick to safer and less direct routes through dense woodlands or mountains in that province, Parcero-Oubiña said. Once a province was peaceful, however, these roads formed vital connections to speed up trade and keep the military on the frontline well supplied with troops and provisions.

Related: Is it safe to eat roadkill?

"The main roads were connecting important places, and so, in one way or another, they all ended or started in Rome, but it's not like you had to go via Rome when traveling from London to Paris, because the network allowed for that to happen," Parcero-Oubiña said. These principal roads were designed for the movement of wheels and animals — in other words, they were far more sophisticated than muddy trails. "They were built with different layers like earth and rock, and then finally big slabs of stone on top. They weren't flat, but kind of dome shaped to allow proper drainage," Parcero-Oubiña said.

"The main roads were connecting important places, and so, in one way or another, they all ended or started in Rome, but it's not like you had to go via Rome when traveling from London to Paris, because the network allowed for that to happen," Parcero-Oubiña said. These principal roads were designed for the movement of wheels and animals — in other words, they were far more sophisticated than muddy trails. "They were built with different layers like earth and rock, and then finally big slabs of stone on top. They weren't flat, but kind of dome shaped to allow proper drainage," Parcero-Oubiña said.

Then came other, secondary dirt roads that weren't paved. They connected smaller towns and cities, rather than offering any sort of a route to Rome.

So, did all Roman roads lead to Rome? No, but an awful lot of the important ones eventually made their way there. The premise of the question might be flawed anyway, said Parcero-Oubiña, because most people going to Rome weren't taking the roads.

"Connection via sea was much more useful because it was faster and cheaper," he said. "If you wanted to go from western Iberia to Rome, for example, then you probably took a boat and not a horse and cart."

Originally published on Live Science.

Benjamin is a freelance science journalist with nearly a decade of experience, based in Australia. His writing has featured in Live Science, Scientific American, Discover Magazine, Associated Press, USA Today, Wired, Engadget, Chemical & Engineering News, among others. Benjamin has a bachelor's degree in biology from Imperial College, London, and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University along with an advanced certificate in science, health and environmental reporting.