New human species 'Dragon man' may be our closest relative

'Dragon man' may be closer to us than Neanderthals.

The skull of an ancient human discovered in northeastern China may belong to a previously unknown human species that scientists have dubbed Homo longi, or "Dragon Man," three new studies report.

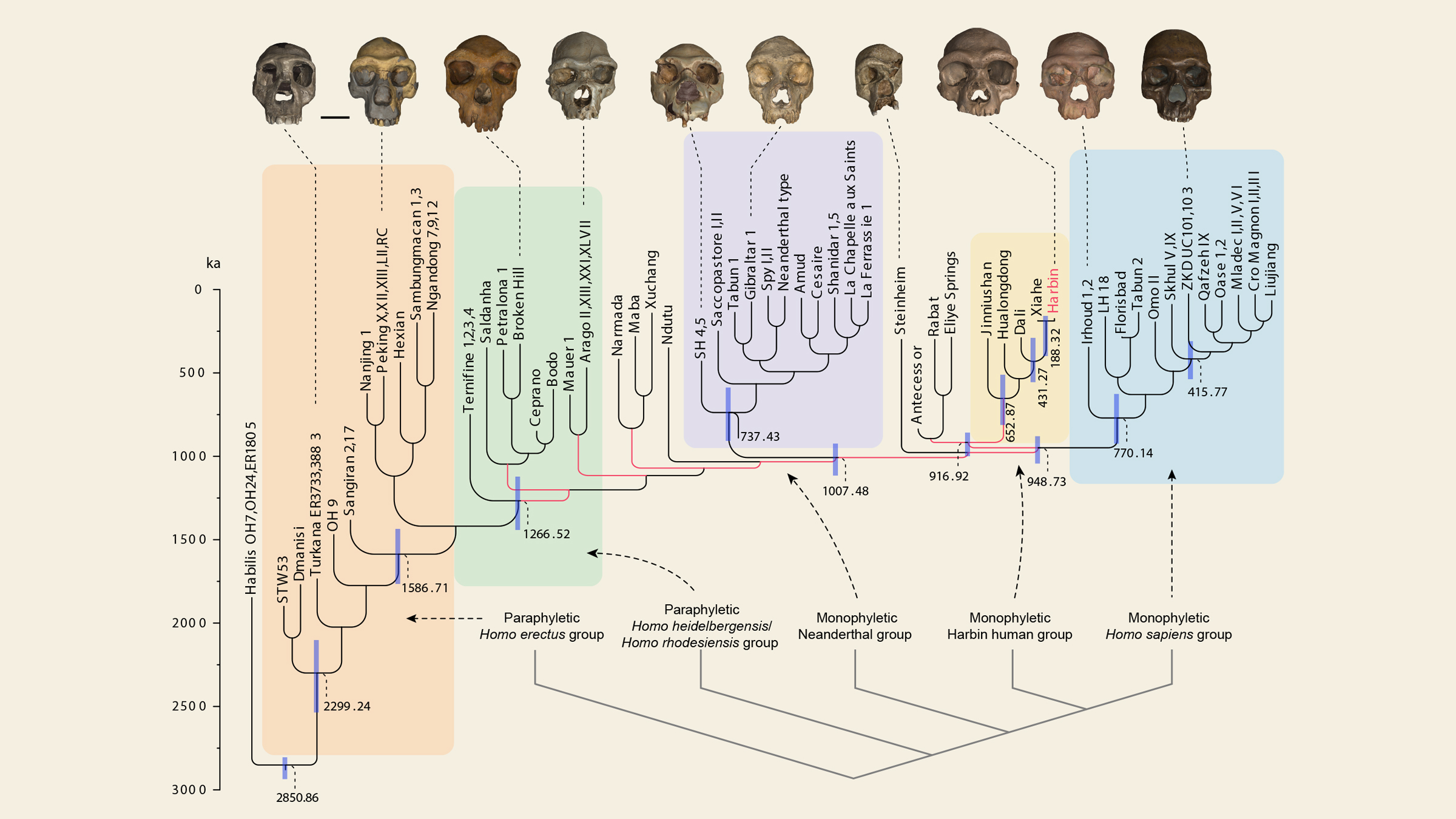

Dragon man's well-preserved skull is the largest Homo skull on record. An analysis of the cranium revealed that Dragon man might be the closest-known related species to Homo sapiens, even closer than Neanderthals, who were long thought to be our closest relation, the study found.

"I was surprised by the resulting phylogeny [family-tree analysis] linking it to H. sapiens rather than H. neanderthalensis, but our conclusions are based on the analysis of large amounts of data," study co-researcher Chris Stringer, a research leader at the Center for Human Evolution Research at the Natural History Museum in London, told Live Science in an email.

However, this interpretation is debatable; it seems possible that this skull belongs to the mysterious Denisovan human lineage, three scientists specializing in human evolution told Live Science.

Related: 10 things we learned about our human ancestors in 2020

The history of Dragon man's skull is worthy of an Indiana Jones movie. A Chinese man reportedly discovered it in 1933 in Harbin City, in Heilongjiang, China's northernmost province. However, the man (kept anonymous by his family) worked as a labor contractor for the Japanese invaders, and chose not to turn over the skull to his Japanese boss. Instead, "he buried it in an abandoned well, a traditional Chinese method of concealing treasures," the researchers wrote in the study. The skull remained there for 85 years, surviving the Japanese invasion, the civil war, the communist movement and the Cultural Revolution, the researchers said. Before the man died, he told his family, who recovered the fossil in 2018 and later donated it to the Geoscience Museum of Hebei GEO University.

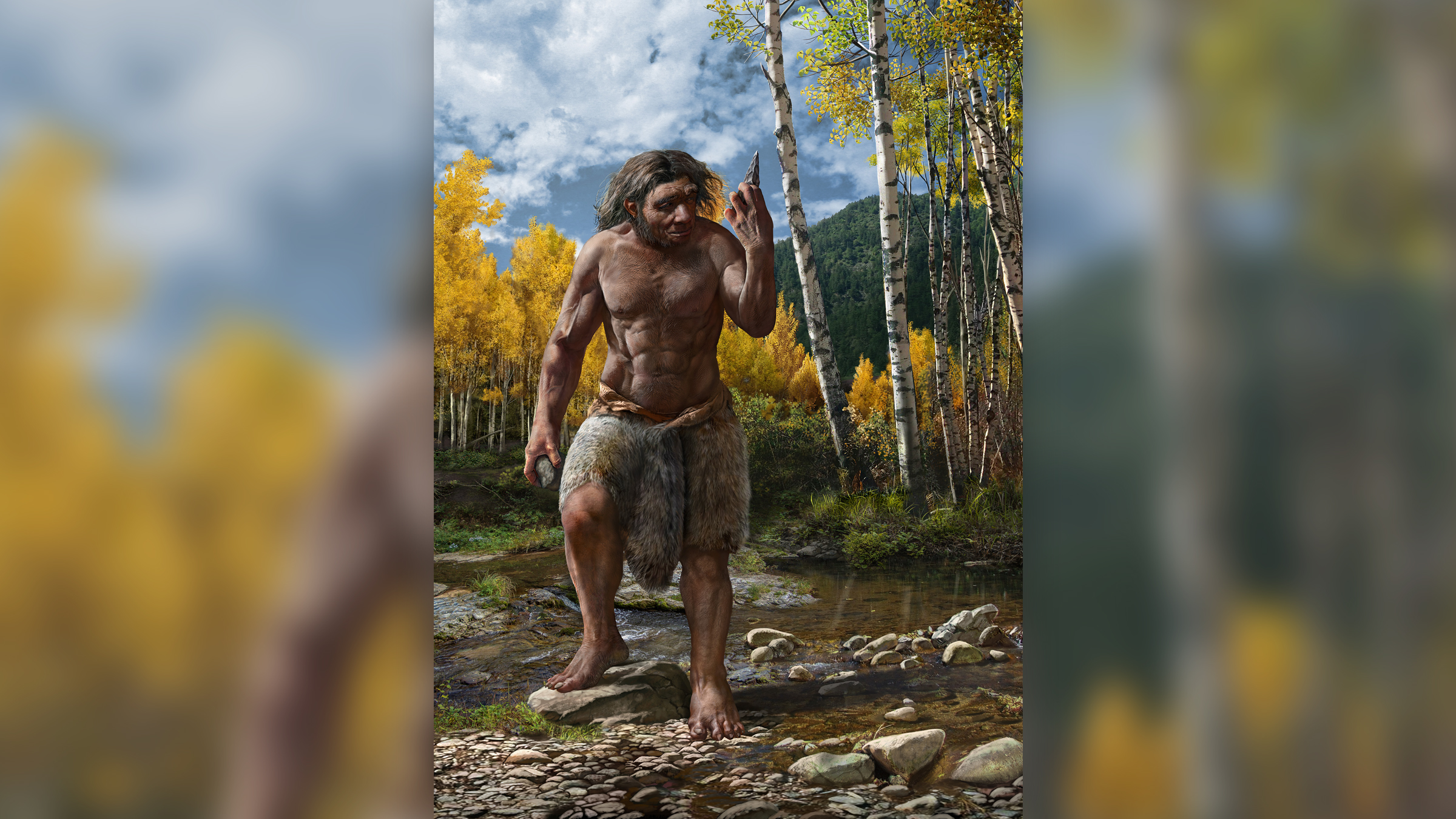

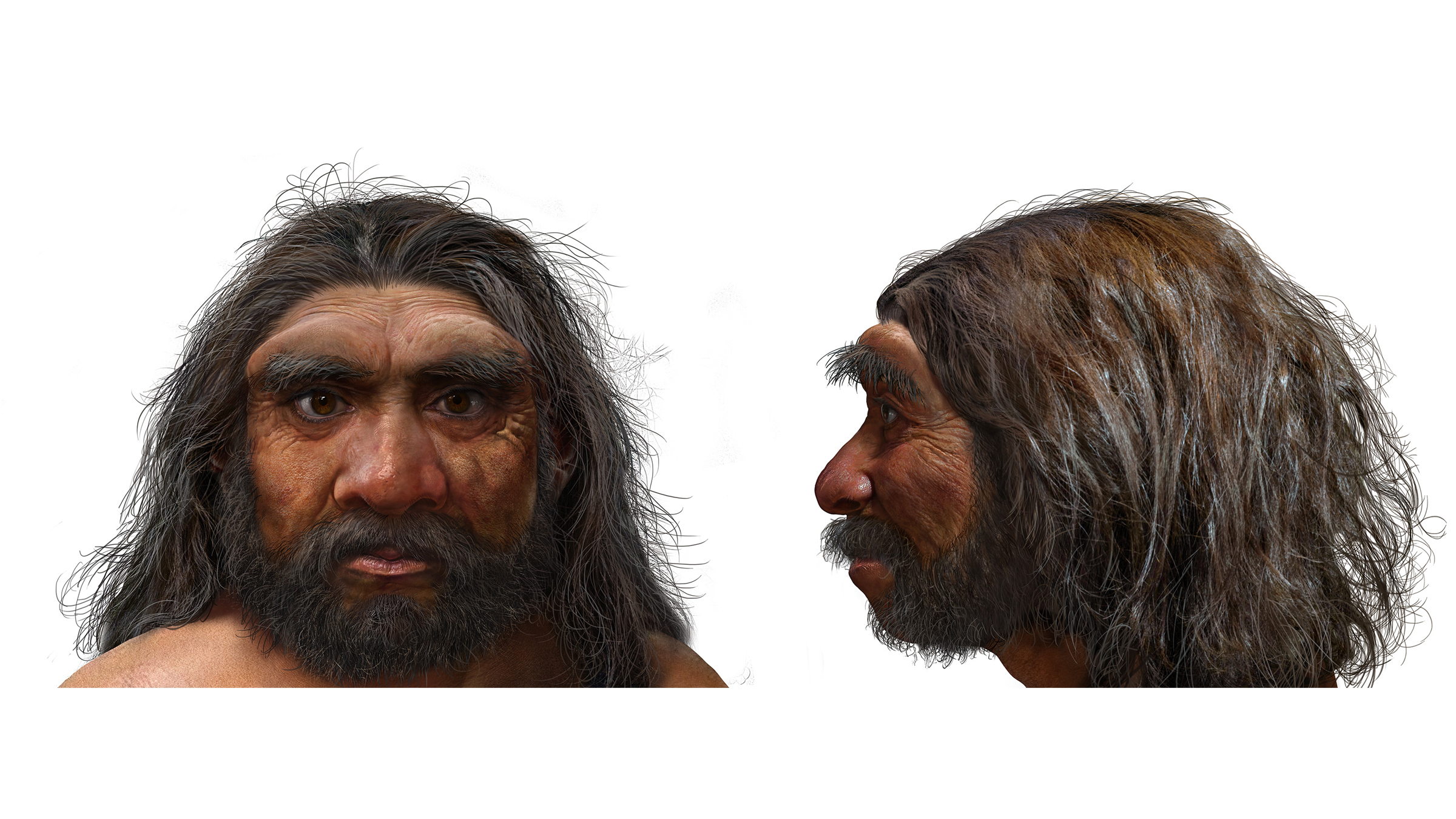

The research team had never seen a skull like this before. "His head was huge — containing a large brain — with a long, low shape and massive brow ridge over the eyes," Stringer said. "His face, nose and jaws were very broad, and he had big eyes. But his face was low in height, with delicate cheekbones, and it was tucked back under the braincase, as in a modern human."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The scientists found slight depressions on the top of Dragon man's head that might be healed wounds, "but we have no evidence of the cause of death," Stringer said. Further analysis determined that the skull likely belonged to a male individual who died at about age 50.

Unique skull

An analysis of the skull revealed "typical archaic human features," but also found "a mosaic combination of primitive and derived characters setting itself apart from all the other previously-named Homo species," study co-researcher Qiang Ji, a professor of paleontology of Hebei GEO University, said in a statement.

When studying the skull, the researchers looked at its shape in detail, analyzing more than 600 traits, Stringer said. Then, the team "used a very powerful computer to build trees of relatedness to other [early human] fossils. After many millions of tree-building processes, we arrived at the most parsimonious trees."

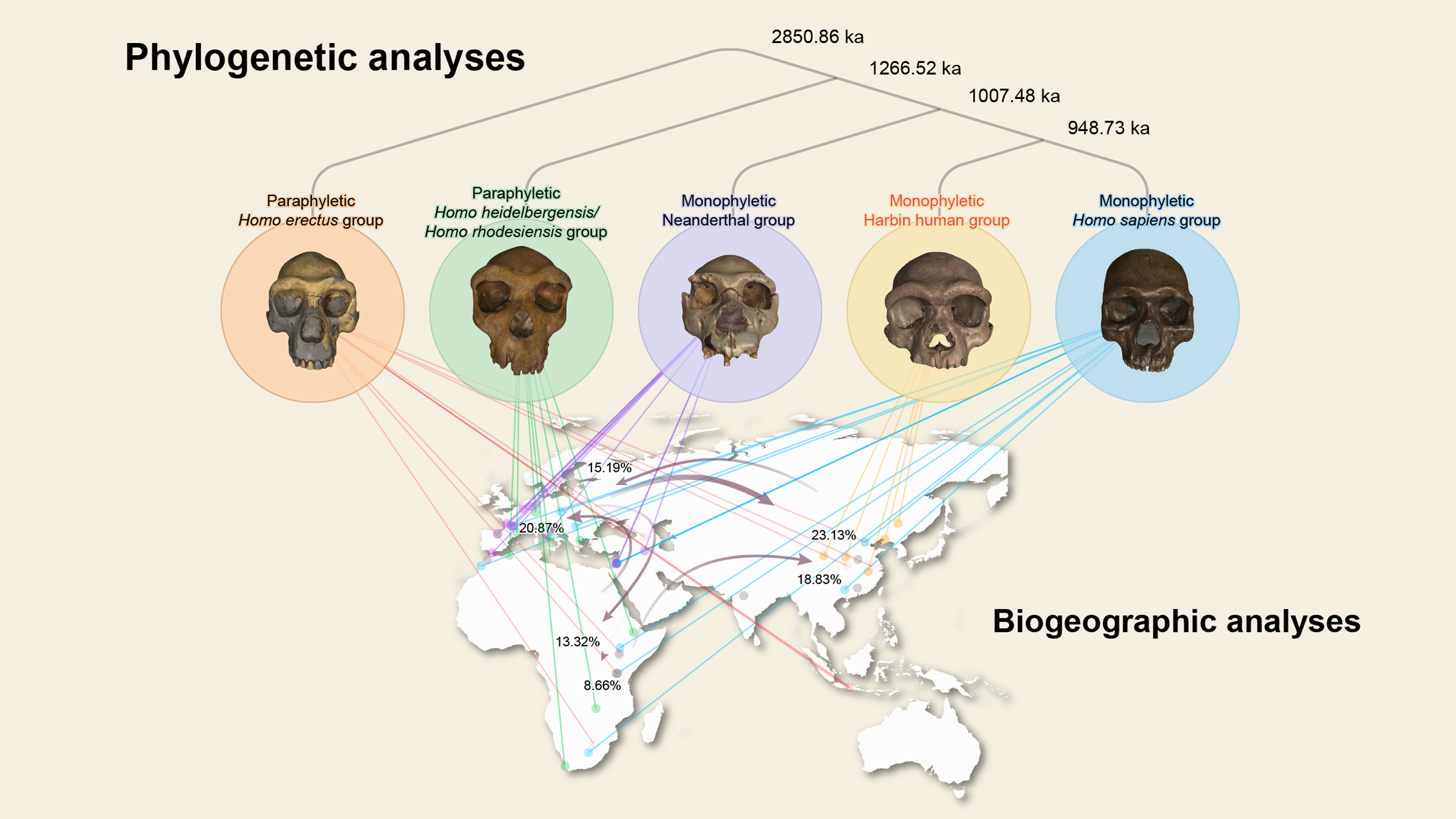

The results suggest that the cranium and a few other fossils from China form a third lineage of humans that lived alongside the Neanderthals and H. sapiens, Stringer said. The family tree indicated that the newly described H. longi is more closely related to H. sapiens than Neanderthals are, he added. In other words, H. longi "shared a more recent common ancestor with us than the Neanderthals did," he said. This would make Dragon man a sister species to H. sapiens, he explained.

The family tree analysis revealed another bombshell: The common ancestor humans share with Neanderthals likely lived more than 1 million years ago, which is about 400,000 years earlier than scientists previously thought, the researchers said.

Related: Denisovan Gallery: Tracing the Genetics of Human Ancestors

Time and place

The man who discovered the skull reportedly found it while working on Dongjiang Bridge in Harbin. To verify that claim, the researchers ran a series of geochemical analyses — they looked at X-ray fluorescence (XRF), rare Earth elements (REE), and strontium isotopes (a variation of strontium) — to investigate the skull's unique chemical makeup. The results supported the claim; Dragon man skull's chemical composition was similar with that of fossils from humans and other mammals found in the Harbin area that date from the middle Pleistocene epoch (2.5 million to 11,700 years ago) to the Holocene epoch (11,700 years ago to present). Dirt struck to the skull's nasal cavity even had matching strontium isotope compositions with a sediment core drilled near Dongjiang Bridge, the researchers found.

The team also dated the skull by looking at the regional stratigraphy (rock layers), and determining the cranium likely came from the Upper Huangshan Formation, which dates to between 309,000 and 138,000 years ago. The researchers were able to narrow that time window by taking tiny samples from the skull to examine the decay rate of the radioactive element uranium, a method that revealed that the cranium is at least 146,000 years old, dating to the middle Pleistocene epoch.

Given this time frame, it's possible that other human species, including H. sapiens, interacted with H. longi, the researchers said. In the middle Pleistocene, Harbin was a forested floodplain. "Like Homo sapiens, they hunted mammals and birds, and gathered fruits and vegetables, and perhaps even caught fish," study lead researcher Xijun Ni, a professor of primatology and paleoanthropology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Hebei GEO University, said in the statement. Based on Dragon man's large size, as well as his location in northeast China, the researchers suggested that H. longi could survive in harsh and cold environments, which helped them migrate through Asia.

Is Dragon man really a Denisovan?

The study's anatomical analyses are "well done" and "impressive," but the conclusions are "too adventurous," three scientists specializing in human evolution, who were not involved with the study told Live Science.

It's possible that the cranium is a Denisovan fossil, all three said. Many think the Denisovans "evolved from an ancestral form called Homo heidelbergensis/ rhodesiensis that dispersed from Africa about 600,000 years ago into Eurasia. In Europe, Homo Heidelbergensis evolved into Neanderthals and in Asia into Denisovans," Silvana Condemi, a paleoanthropologist at Aix-Marseille University in Marseille, France, told Live Science in an email.

Coupled with the fact that the Denisovans are also known from Asia and that the time period that Denisovans and the Harbin skull existed overlap, it's quite possible that Dragon man is a Denisovan, she said.

"I have carefully read the anatomical and phylogenetic study," Condemi said. "The published data leads me to consider this fossil as a particular fossil that could be a Denisovan."

Antonio Rosas, a paleobiologist at the National Museum of Natural Sciences in Spain, agreed that the skull likely belongs to a Denisovan. He added that the authors may have given too much weight to certain evolved facial features on the skull. "These morphological features of the face may be, in fact, primitive characteristics inherited from a common ancestor," Rosas said. "As a result ... the Harbin skull could be associated either with the modern human clade or with the Neanderthal clade." (A clade includes species that share a common ancestor.)

An additional 3D test, known as a geometric morphometric analysis, might shed light on the skull's identity, said Fernando Ramirez Rozzi, director of research specializing in human evolution at France's National Center for Scientific Research in Paris. This analysis lets scientists compare hundreds of traits at once and determines which traits are most important for distinguishing a new group.

While there are precious few Denisovan remains known to scientists, it would be possible to compare the tooth from the Harbin skull with those attributed to Denisovans, Ramirez Rozzi added.

However, the study's researchers said they did consider that the skull was a Denisovan. "I think that Harbin could certainly be a Denisovan, suggested by the very large molar with splayed roots, and the close phylogenetic relationship with the Xiahe jawbone [in northern Tibet], which could be Denisovan," Stringer said. "But until we have a complete Denisovan genome with a complete cranium (or better still, a complete skeleton!), we cannot resolve this question properly, only talk about probabilities."

The three studies were published on Friday (June 25) in the journal The Innovation.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.