The fossil of a duckbill dinosaur has been found on the 'wrong' continent

The final chapter of dinosaur history is a tale stretching across two very different worlds, each a vast supercontinent dominated by its own unique mix of predators and herbivores.

Fossilized remains of a plant eater common to one of the two major land masses have been unexpectedly unearthed in rocks belonging to the other, prompting paleontologists to ask just how it managed to make such a leap.

"It was completely out of place, like finding a kangaroo in Scotland," says University of Bath paleontologist Nicholas Longrich, who led a study on the recent discovery.

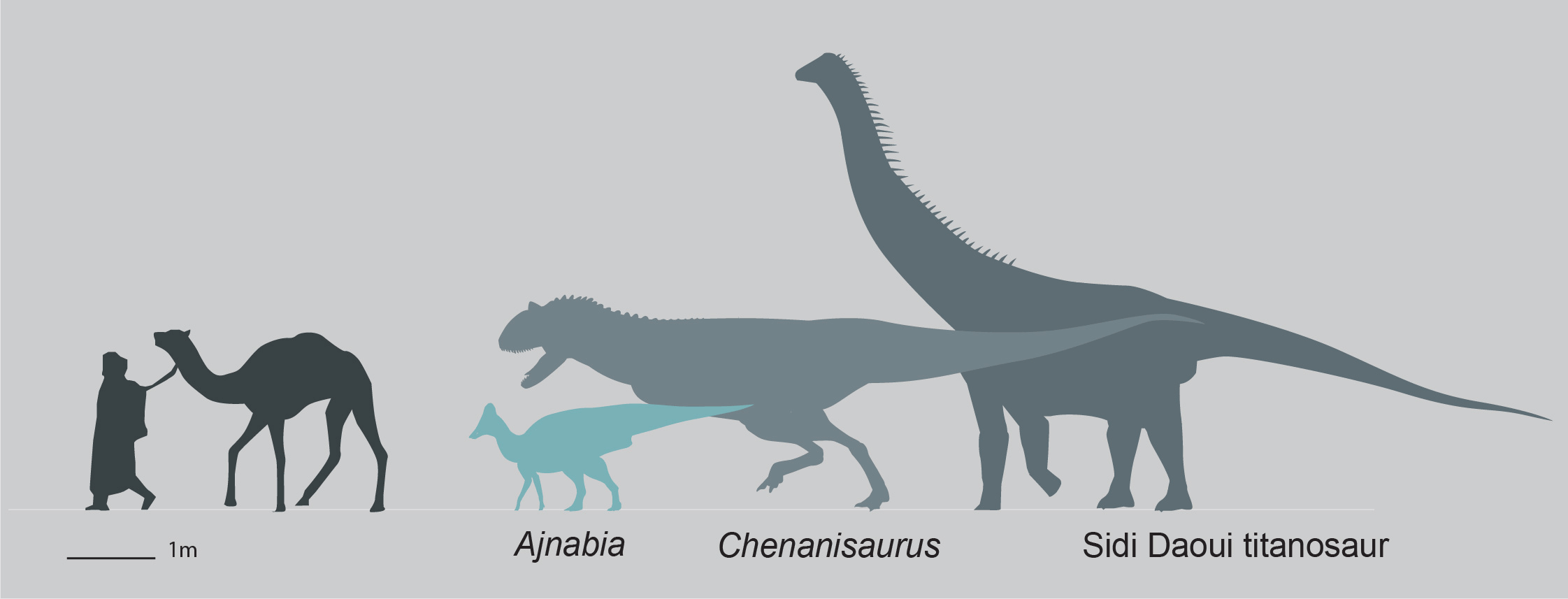

This out-of-place 'kangaroo' was in fact a newly categorized type of crested duckbilled browser known as a hadrosaurid (of a lambeosaurine variety to be precise).

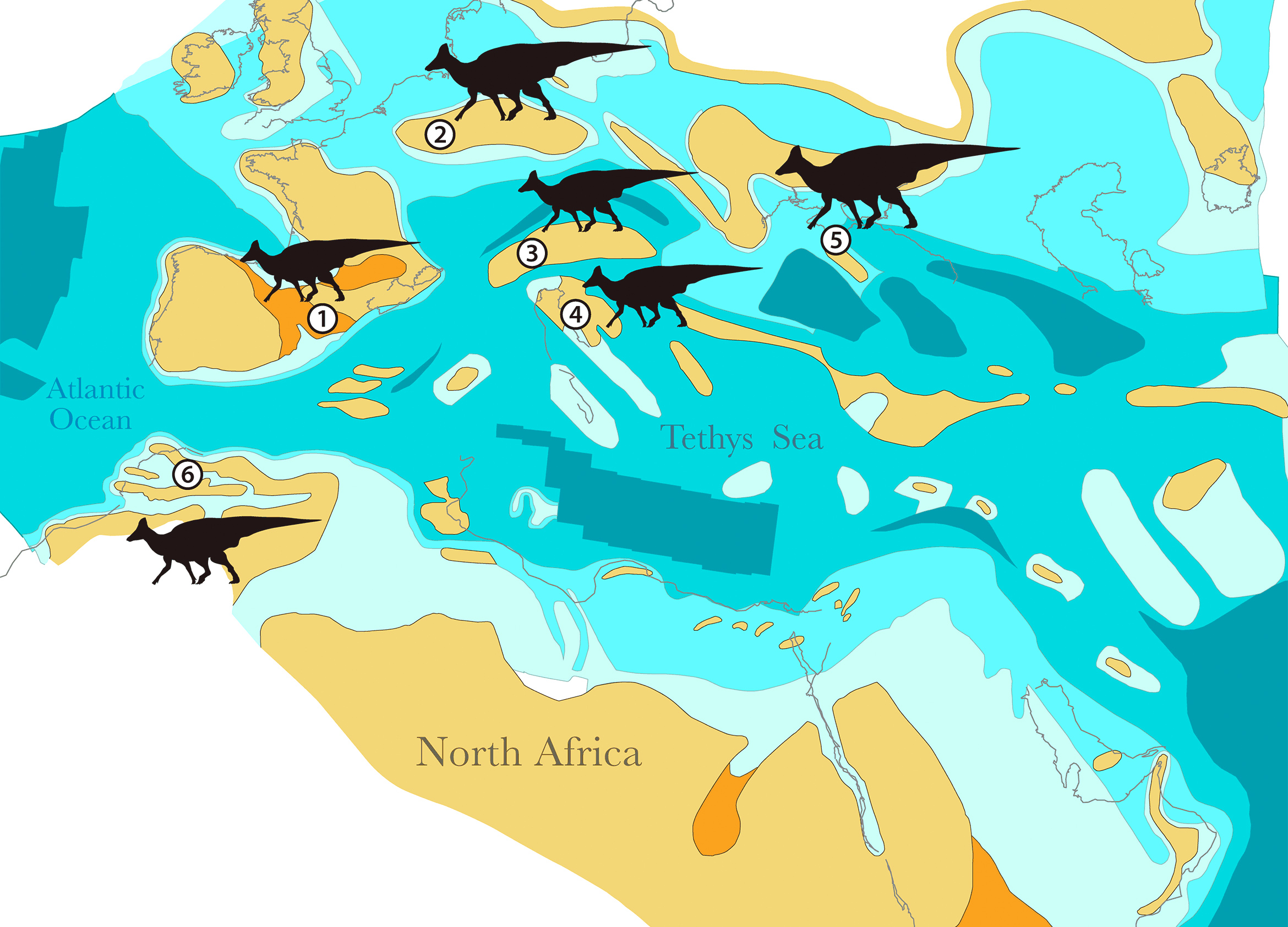

Some 66 million years ago, as the Cretaceous period was drawing to a cataclysmic close, hadrosaurs of many different varieties were among the most common of herbivorous dinosaurs.

At least, that was the case on the supercontinent Laurasia – a mass that would later split to give us today's continents of North America, Europe, and much of Asia.

Far across the ocean, a separate land mass known as Gondwana was instead ruled by a diversity of long-necked, lumbering sauropods.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The remains of these giants are commonly found in places such as Africa, India, Australia, and South America.

Where Hollywood might see fit to mix the two groups together, broad stretches of water between the continents and long periods of isolation meant by the late Cretaceous, duck-bills and long-necks would only have potentially mingled in distinct regions, such as in what is today Europe.

This newest member of the hadrosaurid family just might be a new exception.

Based on little more than some jaw pieces and a handful of teeth pulled out of a phosphate mine in Morocco, the find is evidence that at least one of these animals must have wandered farther out of Laurasia than ever suspected possible.

Well, maybe not wandered, so much as paddled.

"It was impossible to walk to Africa," says Longrich.

"These dinosaurs evolved long after continental drift split the continents, and we have no evidence of land bridges. The geology tells us Africa was isolated by oceans. If so, the only way to get there is by water."

The idea isn't as far-fetched as it might first seem. Hadrosaurs seem quite at home near aquatic environments and come in all shapes and sizes. Some have measured up to 15 meters (45 feet) in length, with large tails and powerful legs capable of making them competent swimmers.

At a more petite 3 meters (9 feet) long, this hadrosaur might have had a little more difficulty making a marathon that could have included hundreds of kilometers of open water.

But theories of smaller animals rapidly crossing oceans on floating rafts of vegetation abound – why not a relatively tiny dinosaur?

"Once-in-a-century events are likely to happen many times. Ocean crossings are needed to explain how lemurs and hippos got to Madagascar, or how monkeys and rodents crossed from Africa to South America," says Longrich.

Combining the Arabic word for foreigner with the name of the famous Greek seafarer, scientists have dubbed the hadrosaur Ajnabia odysseus.

The same assemblage that contained the Ajnabia jaw has given up a rare few other dinosaur bones, including Gondwana staples of titanosaurs and meat-eating theropods called abelisaurs.

It might not be quite enough to reimagine the division between the Cretaceous supercontinents in the moments before an asteroid changed everything. But it should give us enough pause to claim an ocean would be an insurmountable barrier.

"As far as I know, we're the first to suggest ocean crossings for dinosaurs," says Longrich.

This research was published in Cretaceous Research.

This article was originally published by ScienceAlert. Read the original article here.

Mike McRae is a part-time Journalist at ScienceAlert. He has been telling science stories in one form or another for more than 20 years, and expertly navigates a broad range of subjects, from health and neuroscience to the weirdness of quantum physics. From classroom teacher to journalist, Mike has contributed to the CSIRO's magazines, The Guardian, the ABC and Australian Financial Review. He is the author of popular science books "Tribal Science: Brains, Beliefs," and "Bad ideas and Unwell: What Makes a Disease a Disease?" Mike is slowly building a collection of cephalopod tattoos on his right arm and swears there's still room for a nautilus or two.