Earliest evidence of Maya divination calendar discovered in ancient temple

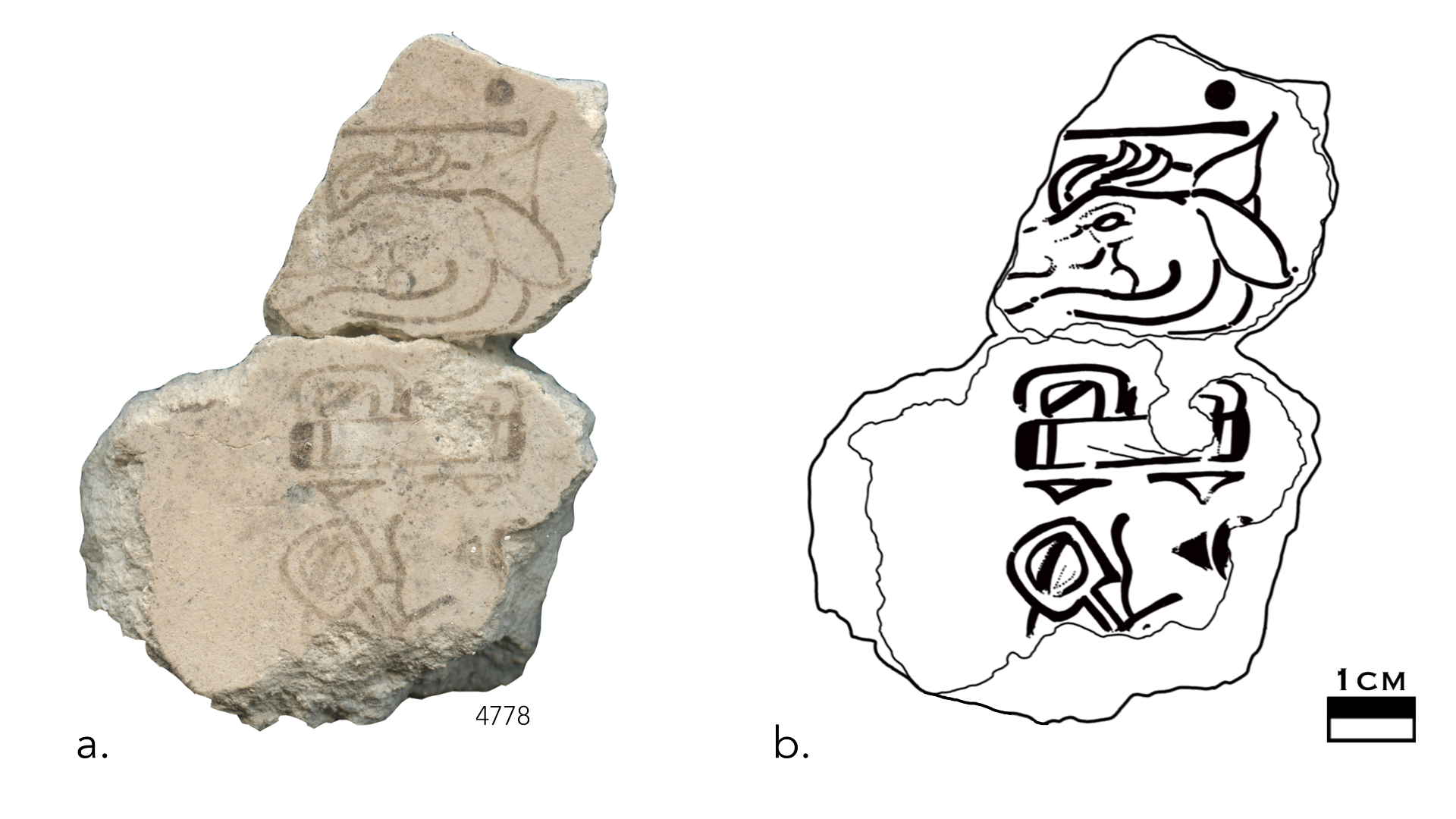

Pieced together, two ancient fragments say "7 deer."

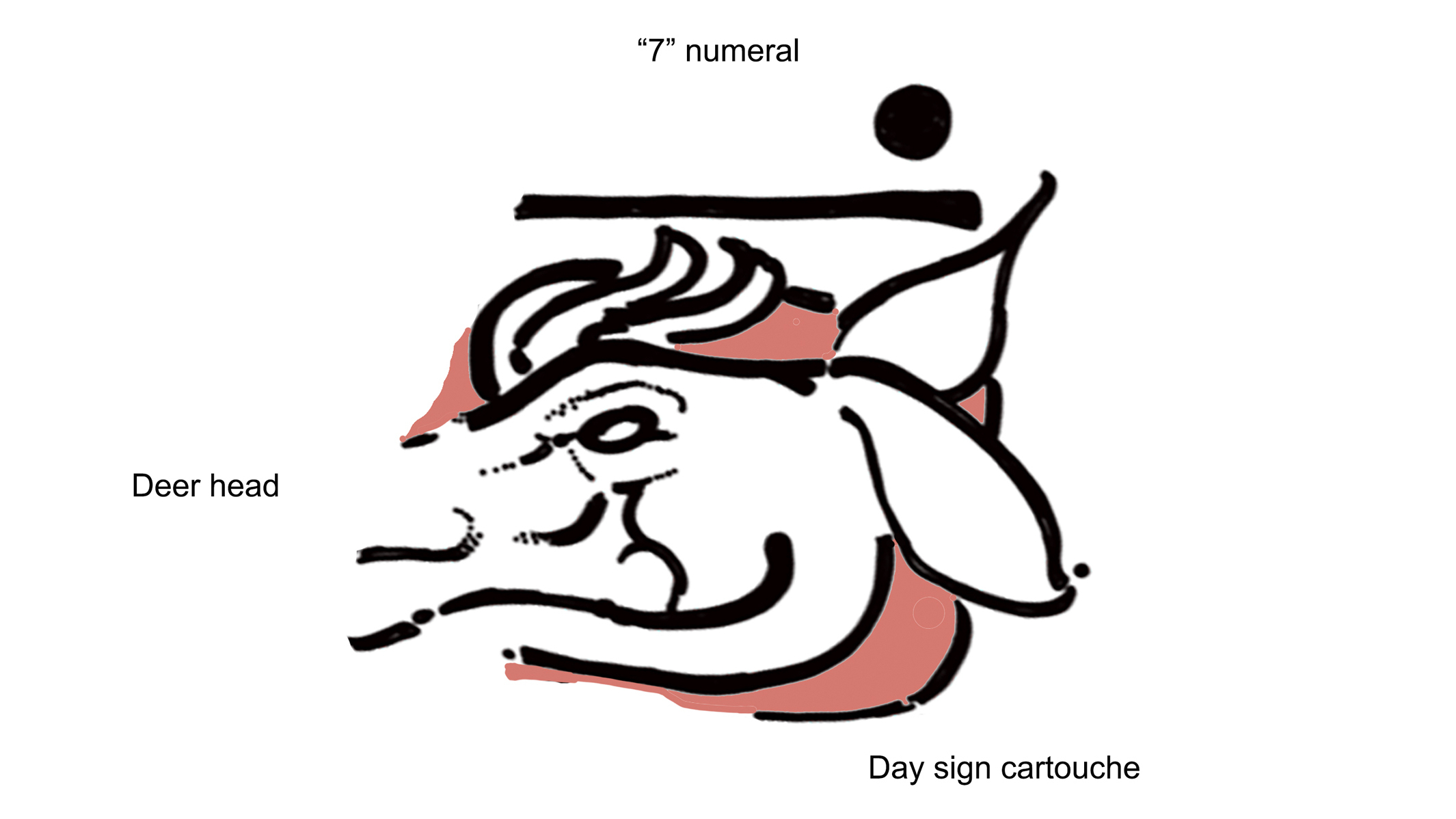

Archaeologists in Guatemala have discovered the oldest evidence of the Maya calendar on record: two mural fragments that, when pieced together, reveal a notation known as "7 deer," a new study finds.

The two "7 deer" fragments date to between 300 B.C. and 200 B.C., according to radiocarbon dating done by the research team. This early date indicates that this Maya divination calendar, which was also used by other pre-Columbian cultures in Mesoamerica, such as the Aztecs, has been in continuous use for at least 2,300 years, as it is still followed today by modern Maya, the researchers said. (Notably, this is not the Long Count calendar that some people used to suggest the world was going to end in 2012.)

"It's the one calendar that survives all the conquests and the civil war in Guatemala," the latter of which was waged from 1960 to 1996, study first author David Stuart, the Schele professor of Mesoamerican art and writing at the University of Texas at Austin, told Live Science. "The Maya of today in many communities have kept it as a way of connecting to their ideas of fate and how people relate to the world around them. It's not a revival. It's actually a preservation of the calendar."

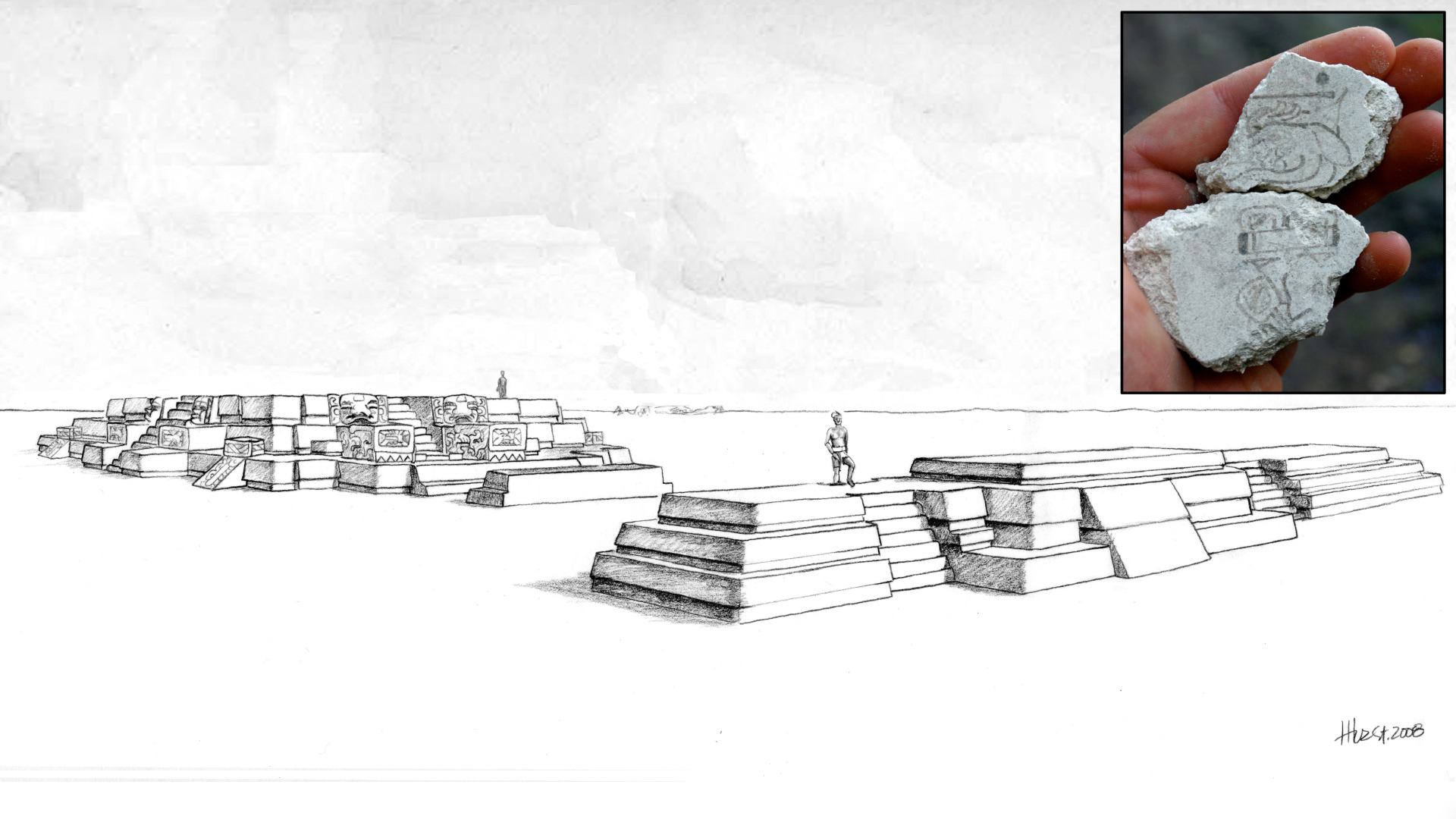

The researchers found the mural fragments at the archaeological site of San Bartolo, northeast of the ancient Maya city of Tikal. Stuart was part of the team that discovered San Bartolo in 2001. "It's in the remote jungles of northern Guatemala" and famous for its Maya murals dating to the Late Preclassic period (400 B.C. to A.D. 200), he said.

Related: Why did the Maya civilization collapse?

The murals at San Bartolo are in a massive complex known as Las Pinturas, which the Maya built over hundreds of years. Every so often, the Maya would build over an old complex, constructing larger and more impressive structures. As a result, Las Pinturas is layered like an onion. If archaeologists tunnel into its inner layers, they can find earlier structures and murals, Stuart said.

The researchers collected ancient organic material, such as charcoal, within the layer where the mural fragments were discovered. By radiocarbon-dating these fragments, they could estimate when the murals were created.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, these murals weren't in one piece. In total, the team discovered about 7,000 fragments from various murals. Of this colossal collection, the team analyzed 11 wall fragments, discovered between 2002 and 2012, with radiocarbon dating. These included the two pieces that formed the "7 deer" notation, which includes a glyph, or image of a deer under the Maya symbol for the number seven (a horizontal line with two dots over it).

Four Maya calendars

The Maya had four calendars, as "they were very interested in timekeeping," Stuart said. "They had very elaborate and elegant ways of tracking time."

One is the sacred divination calendar, or Tzolk'in, from which this "7 deer" notation originates. This calendar has 260 days consisting of a combination of 13 numbers and 20 days that have different signs (like deer).

The 260 days don't make up a year, however. Rather, it's a cycle similar to the seven-day week. The notation "7 deer" doesn't give you a date; it doesn't tell you the season or year in which something happened. "It's like saying Napoleon invaded Russia on a Wednesday," Marcello Canuto, director of the Middle American Research Institute at Tulane University, who wasn't involved with the study, told Live Science.

Related: Did the Maya really sacrifice their ballgame players?

Today, the 260-day cycle in the Tzolk'in calendar is used for soothsaying and ceremonial record keeping, Stuart said. "There are date keepers, as they're called, in Guatemala today," Stuart said. "If you said the day is 7 deer, they would go, 'Oh yeah, 7 deer, that means this, this and this.'"

The other Maya calendars are the Haab', a solar calendar that lasts 365 days but doesn't account for a leap year; a lunar calendar; and the Long Count calendar, which tracks major time cycles and caused a lot of brouhaha in when some people (mistakenly) thought it was foretelling the end of the world in 2012, Live Science previously reported.

"[I remember] all that nonsense back in 2012 about the end of a cycle," Stuart said. "Everyone was saying, 'It's the end of the calendar.' But no, they didn't understand there was yet another cycle after that."

There are other calendar notations that might be older than the newly described 7-deer finding, but these artifacts are challenging to date because they were carved into stone (which does not hold any radioactive carbon that can be dated). Moreover, these carved stones were possibly moved around, meaning a date from the site might not reflect the date of these calendars, Stuart said. For instance, a proposed Tzolk'in calendar found in Oaxaca Valley, Mexico has dates ranging from 700 B.C. to 100 B.C., according to several studies.

When these four types of calendars are taken into account, this "7 deer" notation is the "earliest evidence of any Maya calendar, possibly [the] earliest securely dated evidence anywhere in Mesoamerica," Stuart said.

Surprising deer

The archaeologists were surprised to find the deer glyph. Later Maya Tzolk'in notations almost always write out the word for deer rather than drawing a glyph of the animal, Stuart said. In effect, these fragments might be evidence of an early stage of Maya script, he said.

"We speculate a little bit in the article that it may be that this is an early phase of the writing system where they haven't quite established the norms that we're used to," Stuart said. He added that it's unclear where in Mesoamerica this calendrical system began.

These two lines of evidence help tie everything together, Canuto noted. "The text seems to suggest something really archaic, and then the radiocarbon and the context of the dating seems to support that," he said.

The study is "meticulously done," Walter Witschey, a retired research professor of anthropology and geography at Longwood University in Virginia and a research fellow at the Middle American Research Institute, told Live Science in an email. The finding is "evidence for the earliest known calendar notation from the Maya region," he said.

The study was published online Wednesday (April 13) in the journal Science Advances.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.