Ancient papyrus holds the world’s oldest guide to mummification

The scroll contains the oldest known instructions for embalming the dead.

The oldest known instructions for the ancient art of embalming mummies were recently discovered on a medical papyrus from ancient Egypt.

How-to descriptions of the mummification process are exceptionally rare in the archaeological record — only two other such "manuals" are known. This newest example, found in an ancient scroll dating to around 1450 B.C., predates other mummification texts by more than 1,000 years. The guide contains many helpful suggestions, such as how to make herbal insect repellent and using red linen wrappings to reduce facial swelling.

Sofie Schiødt, a research assistant in the Department of Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies at the University of Copenhagen, discovered the embalming manual while translating a papyrus for her doctoral thesis, which will be published in 2022, university representatives said in a statement.

Related: Image gallery: Mummy evisceration techniques

Half of the papyrus scroll is in the university's Papyrus Carlsberg Collection, and the other half is in the Louvre Museum in Paris. Prior to that, each piece was privately owned, and they were acquired by the university and the Louvre in 2015 and 2006, respectively, Schiødt told Live Science in an email. It wasn't until 2018 that experts learned that the two pieces were part of the same scroll.

In its entirety, the papyrus measures nearly 20 feet (6 meters) long and is inscribed on both sides. It is the second-longest medical papyrus from ancient Egypt, and Schiødt's translation project relies mostly on high-resolution photographs of the precious artifact.

"This way we can move displaced fragments around digitally, as well as enhance colors to better read passages where the ink is not so well-preserved," Schiødt said. "It also aids in reading difficult signs when you can zoom in on the high-res photos."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Succinct recipes

There are five sections in the medical papyrus. In the first are short medical recipes, followed by a section on herbs. Next is a long section on skin diseases, followed by the embalming manual, "and finally another section of succinct medical recipes," Schiødt said.

Only a small portion of the papyrus — just three columns of text — covers embalming. Though the mummification section is brief, it's packed with details, many of which were absent from later embalming texts.

"Several recipes are included in the manual describing the manufacturing of various aromatic unguents," Schiødt told Live Science, referring to substances used as ointments. However, some parts of the embalming process, such as drying the corpse with natron — a desiccating compound made of sodium carbonate and sodium bicarbonate (salt and baking soda) — aren't described at length.

"As such, the text reads mostly as a memory aid, helping the embalmer remember the most intricate parts of the embalming process," she said.

According to the manual, embalming a person took 70 days, and the task was performed in a special workshop near the person's grave. The two main stages — drying and wrapping — each lasted 35 days.

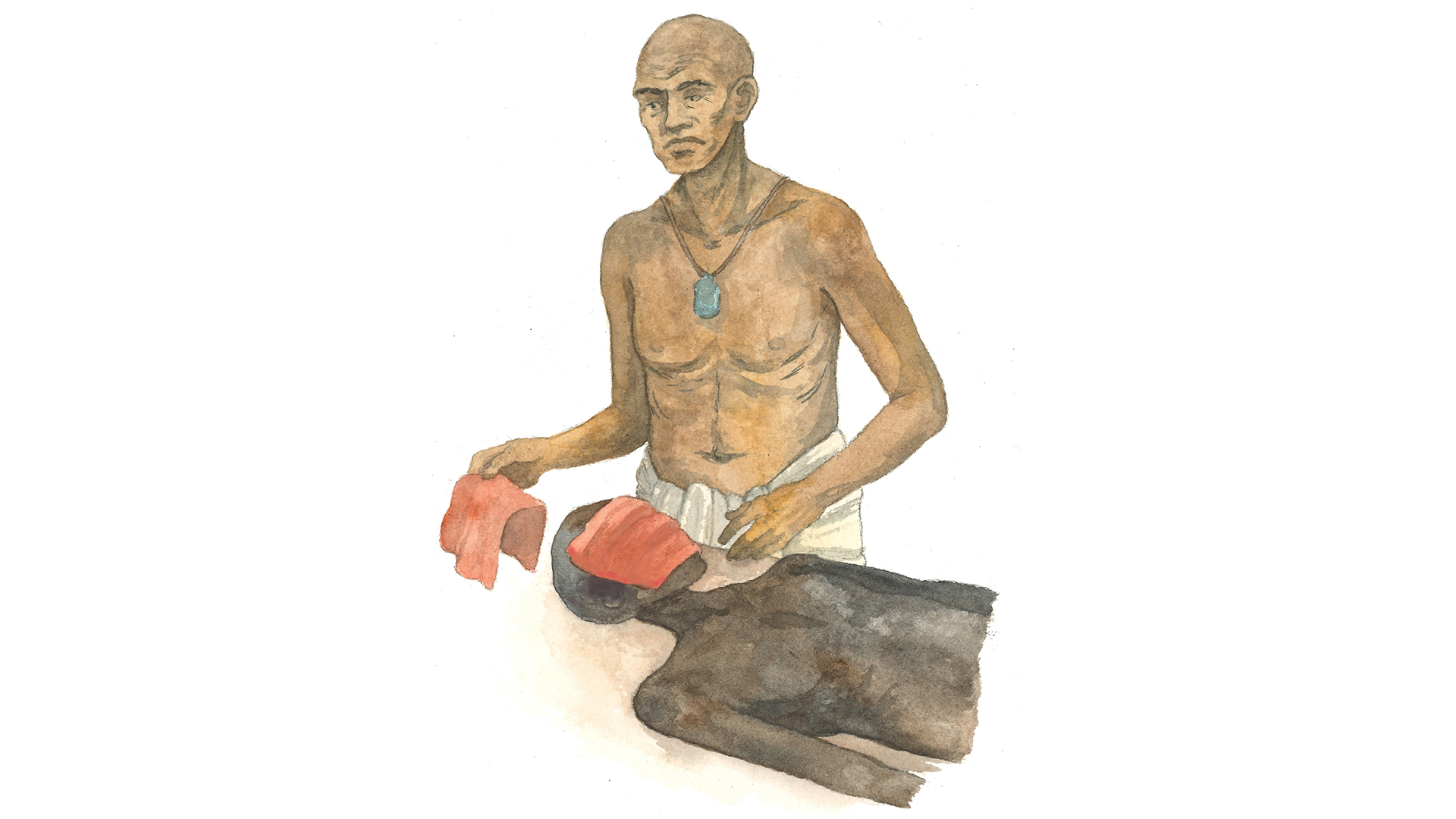

Schiødt said that one of the exciting new pieces of information from the text involves a procedure for embalming a dead person's face. The instructions include a recipe that combines plant-based aromatics and binders, cooking them into a liquid "with which the embalmers coat a piece of red linen," she said.

"The red linen is then applied to the dead person's face in order to encase it in a protective cocoon of fragrant and anti-bacterial matter," and this was repeated every four days, according to the study. On days when the embalmers were not actively treating the body, they covered it with straw infused with aromatic oils "in order to keep insects and scavengers away," according to Schiødt.

Work on the mummy typically wrapped up by day 68, "after which the final days were spent on ritual activities allowing the deceased to live on in the afterlife," Schiødt wrote.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.