Primate ancestor of all humans likely roamed with the dinosaurs

Our ancient ancestors looked like squirrels.

Scientists have identified the earliest primate fossils: tiny ancient teeth from a rat-size creature that suggest our ancient ancestors once lived alongside the dinosaurs.

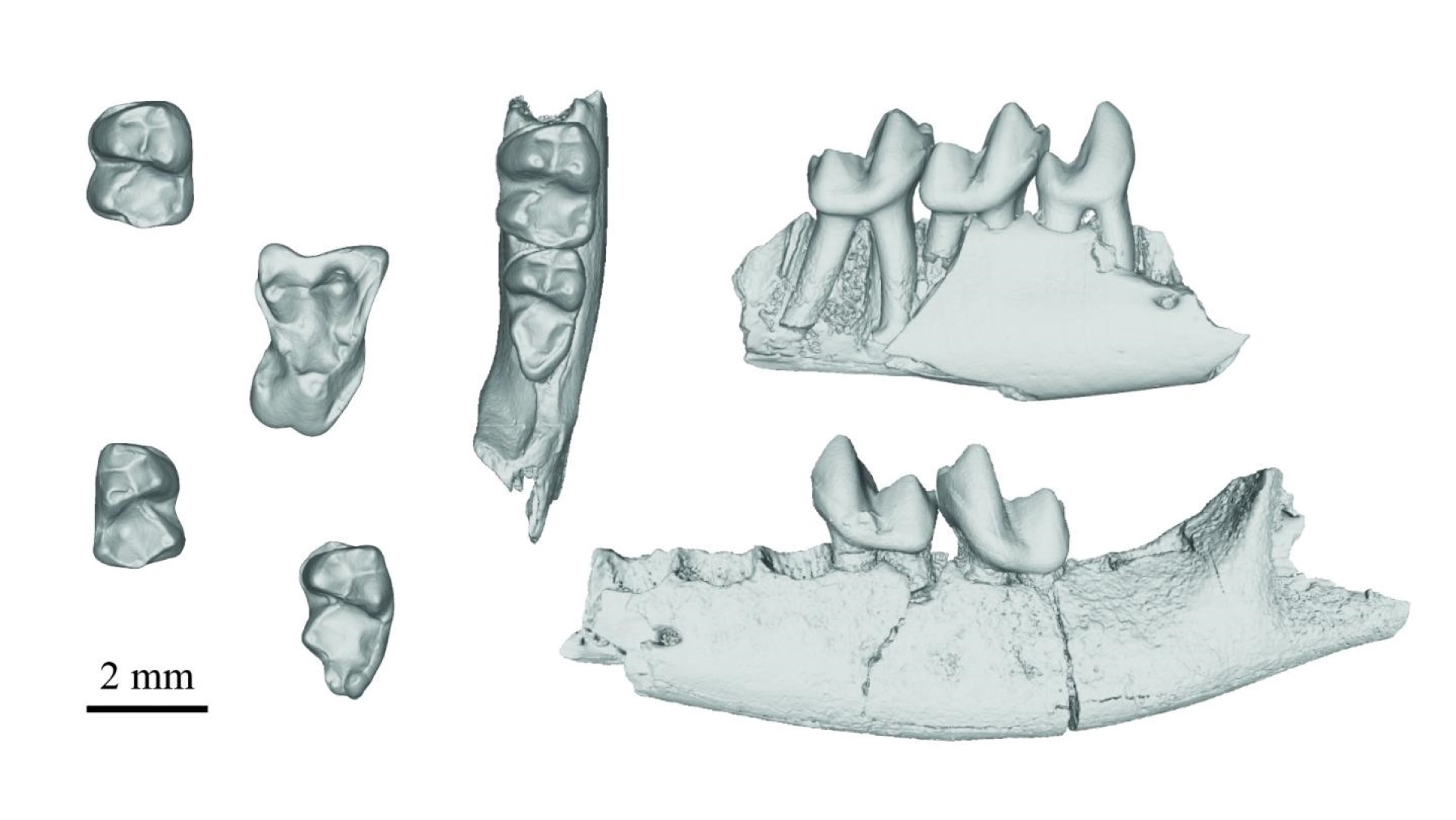

The teeth are 0.08 inches (2 millimeters) long and are from the oldest group of primates, known as plesiadapiforms. They were found in the Fort Union Formation in northeastern Montana in the 1980s, but have now been formally identified in a new study, published Feb. 24 in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

These early primates represent life beginning to recover after the giant asteroid slammed into Earth at the end of the Cretaceous period about 66 million years ago, causing a mass extinction that wiped out nonavian dinosaurs. The researchers dated the fossils to between 105,000 and 139,000 years after the extinction event; but these creatures likely evolved from an unknown ancestor primate that lived alongside the dinosaurs, the researchers said.

"It's our lineage, so it has a special meaning to us. And to think about, you know, our earliest ancestors at this time in northeastern Montana living alongside dinosaurs perhaps and then surviving this [extinction] event is pretty breathtaking to me," co-lead author Gregory Wilson Mantilla, a professor in the Department of Biology at the University of Washington and curator of vertebrate paleontology at the university's Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, told Live Science.

Related: Photos: Fossils reveal pint-size primate

Plesiadapiforms are the ancestors of all modern primates, including humans. The five fossils in the new study belong to a genus called Purgatorius — named after fossils found on Purgatory Hill in Montana, which included those from members of the oldest and most primitive Plesiadapiform family, Purgatoriidae, and, therefore key to understanding how early primates evolved.

The research team analyzed the tiny teeth with CT scans, using X-rays to create 3D images of body parts; they produced larger copies using a 3D printer for easier examination. Two of the teeth came from the species Purgatorius janisae, and the other three teeth have been assigned to a new species named Purgatorius mckeeveri.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The newly described P. mckeeveri is named after Frank McKeever, who was one of the first residents of the area where the fossils were found and whose family has supported the fieldwork there, according to a statement released by the University of Washington.

P. mckeeveri had inflated and rounded cusps on its teeth, which were suitable for crushing fruits, whereas the sharper teeth of P. janisae were better for eating insects. The two species, however, were related and likely looked very similar, perhaps even indistinguishable, Mantilla said.

"They were probably quite squirrel-like in appearance," Mantilla said. They had much longer snouts compared with those of modern short-faced primates, he added, and their eyes were on the sides of their heads, as they relied more heavily on their sense of smell. The researchers helped to create a reconstruction of P. mckeeveri based on information gathered from the teeth and what is known about Purgatorius, and their close relatives, from previous fossil discoveries, such as ankle bones.

The fossils were found in rock estimated to be about 65.9 million years old. The ancient teeth may help scientists like Mantilla understand how life survived the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction and recovered through the Paleogene period (about 66 million to 23 million years ago) and beyond.

"What we're seeing is that part of this recovery strongly involved our lineage," Mantilla said. Primates were among the first major group to flourish, by finding gaps in the rebounding ecosystems. "They were living in the trees, whereas most mammals were living low on the ground," Mantilla said.

Mary Silcox, a professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Toronto Scarborough who focuses on plesiadapiforms, said the study was "very exciting."

To have identifiable primates from the very earliest periods of the Paleogene clearly suggests that placental mammals must have started to diversify in the last days of the nonavian dinosaurs, Silcox told Live Science in an email. "The fact that this material comes from North America is also significant, supporting the importance of this continent in the earliest phases of primate evolution."

Originally published on Live Science.

Patrick Pester is the trending news writer at Live Science. His work has appeared on other science websites, such as BBC Science Focus and Scientific American. Patrick retrained as a journalist after spending his early career working in zoos and wildlife conservation. He was awarded the Master's Excellence Scholarship to study at Cardiff University where he completed a master's degree in international journalism. He also has a second master's degree in biodiversity, evolution and conservation in action from Middlesex University London. When he isn't writing news, Patrick investigates the sale of human remains.