Assyrian Tablets Contain Earliest Written Record of Aurora’s Sky Glow

Carved references to an aurora predate known records by nearly a century.

Ancient Assyrian stone tablets represent the oldest known reports of auroras, dating to more than 2,500 years ago.

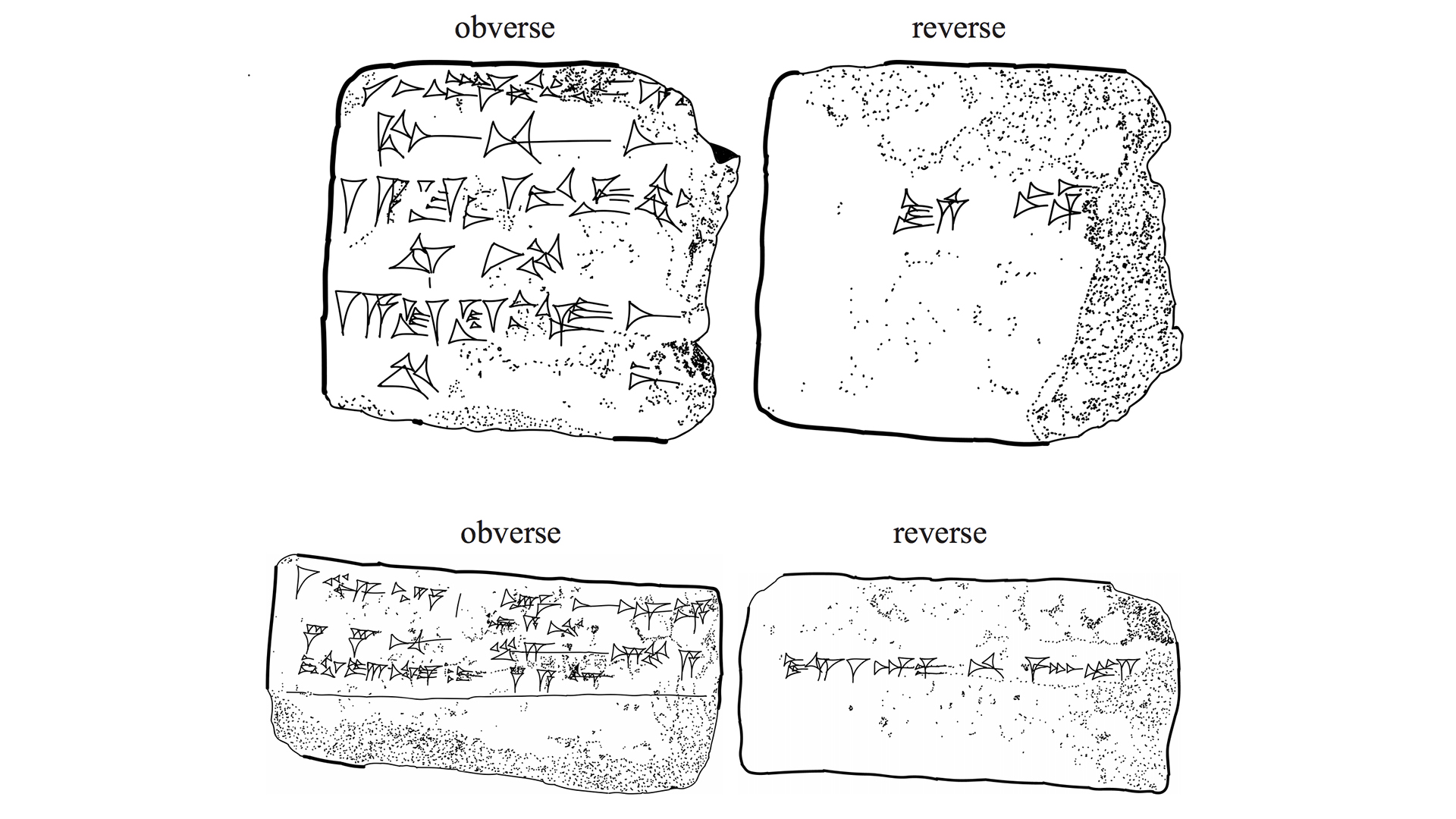

The descriptions, written in cuneiform, were found on three stone tablets, dating from 655 B.C. to 679 B.C. They predate other known historical references to auroras by about a century, researchers reported in a new study.

Auroras are dazzling light shows that take place when waves of charged particles from the sun collide with Earth's magnetic field. Earth was likely visited by an immense solar storm around the seventh century B.C., and the auroras described in the tablets may have been the result of that powerful solar activity, the study authors wrote online Oct. 7 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Related: Northern Lights: 8 Dazzling Facts About Auroras

Ancient skygazing accounts, such as the ones on these Assyrian tablets, help scientists to piece together a more complete picture of Earth's cosmic tango with its solar partner. Because telescope observations have been around for a mere 400 years, they provide "only a very small snapshot at best" of how our sun behaves, said lead study author Hisashi Hayakawa, an astrophysicist at Osaka University in Japan and a visiting researcher at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in the United Kingdom.

Earlier this year, another team of researchers found that a massive solar storm, about 10 times stronger than any in modern history, swept over Earth around 2,600 years ago. Fingerprints of this storm's intense geomagnetic bombardment were left behind as radioactive atoms trapped in Greenland's ice, Live Science previously reported.

The authors of the new study wondered if Assyrian astrologists from that period might have recorded anything unusual that could be linked to the solar storm. The researchers investigated 389 reports on cuneiform tablets in the collection of the British Museum; most of the reports described planetary and lunar activity. But three records noted phenomena that were likely candidates for auroras: "red glow," "red cloud" and "red sky," according to the study.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"These descriptions themselves are quite consistent with the early modern descriptions of auroral display," Hayakawa told Live Science in an email. Indeed, red is a color typically found in low-altitude auroras and in auroras produced by low-energy electrons, the researchers reported.

Today, auroras in the Northern Hemisphere are usually associated with regions close to the North Pole. But Earth's magnetic field is dynamic and changing, and thousands of years ago, magnetic north was about 10 degrees closer to the Middle East than it is today, increasing the likelihood of spectacular aurora displays in that part of the world, the study authors reported.

And even during the late 19th century, auroras were still glimpsed in Cairo; Baghdad; and Alexandria, Egypt, Hayakawa added.

"When you have significant magnetic storms, it is not something extremely surprising to see aurorae in the Middle East, even in the (early) modern period," Hayakawa said.

The infrequency of those descriptions in the Assyrian records suggested that what the writers had witnessed was something out of the ordinary and not, for example, a reddened sky that might accompany a vivid sunset, Hayakawa said.

Prior to this discovery, the earliest known reference to an aurora was in a Babylonian tablet known as the "Astronomical Diaries," dating to 567 B.C. The Assyrian records "allow us to trace the history of solar activity back a century earlier than the earliest existing datable auroral reports," according to the study.

- Photos: Ancient Inscriptions Tell of Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal II

- In Images: Rising 'Phoenix' Aurora and Starburst Galaxies Light Up the Skies

- Aurora Images: See Breathtaking Views of the Northern Lights

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.