Hobbits and other early humans not 'destructive agents' of extinction, scientists find

Here's how we know.

When it comes to causing extinctions, early humans were likely not the jerks that we are today, a new study finds.

Early humans relatives have lived on islands since the early Pleistocene epoch (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago). But widespread extinction on islands can largely be traced back to the past 11,700 years during the Holocene epoch, when modern humans began wreaking havoc there — overhunting, altering habitats and introducing invasive species, the researchers found.

"While humans are directly or indirectly responsible for many hundreds of losses on islands in the past several hundred years, that trail of woe grows very thin the earlier you go back in time," study co-author Ross MacPhee, senior curator of vertebrate zoology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, told Live Science in an email. "Their [our distant relatives'] impact was trivial, whereas ours is, and has long been, catastrophic."

Related: 10 extinct giants that once roamed North America

Why islands?

Islands are rife with animal extinctions. Take, for instance, the New Zealand islands where nine species of moa, a giant, ostrich-like bird, used to live. But within 200 years of human arrival, they all went extinct, along with at least 25 other species of vertebrates (animals with backbones), the researchers wrote in the study.

The team, led by scientists at Griffith University in Australia, focused on islands for one big reason: They're "particularly prone to widespread extinction," they wrote in the study. That's because islands tend to have animals that are smaller in size and population, have animals with lower genetic diversities (in part, because of inbreeding), are more susceptible to random events, provide less opportunity for recolonization and support higher levels of native animals compared with those on continents.

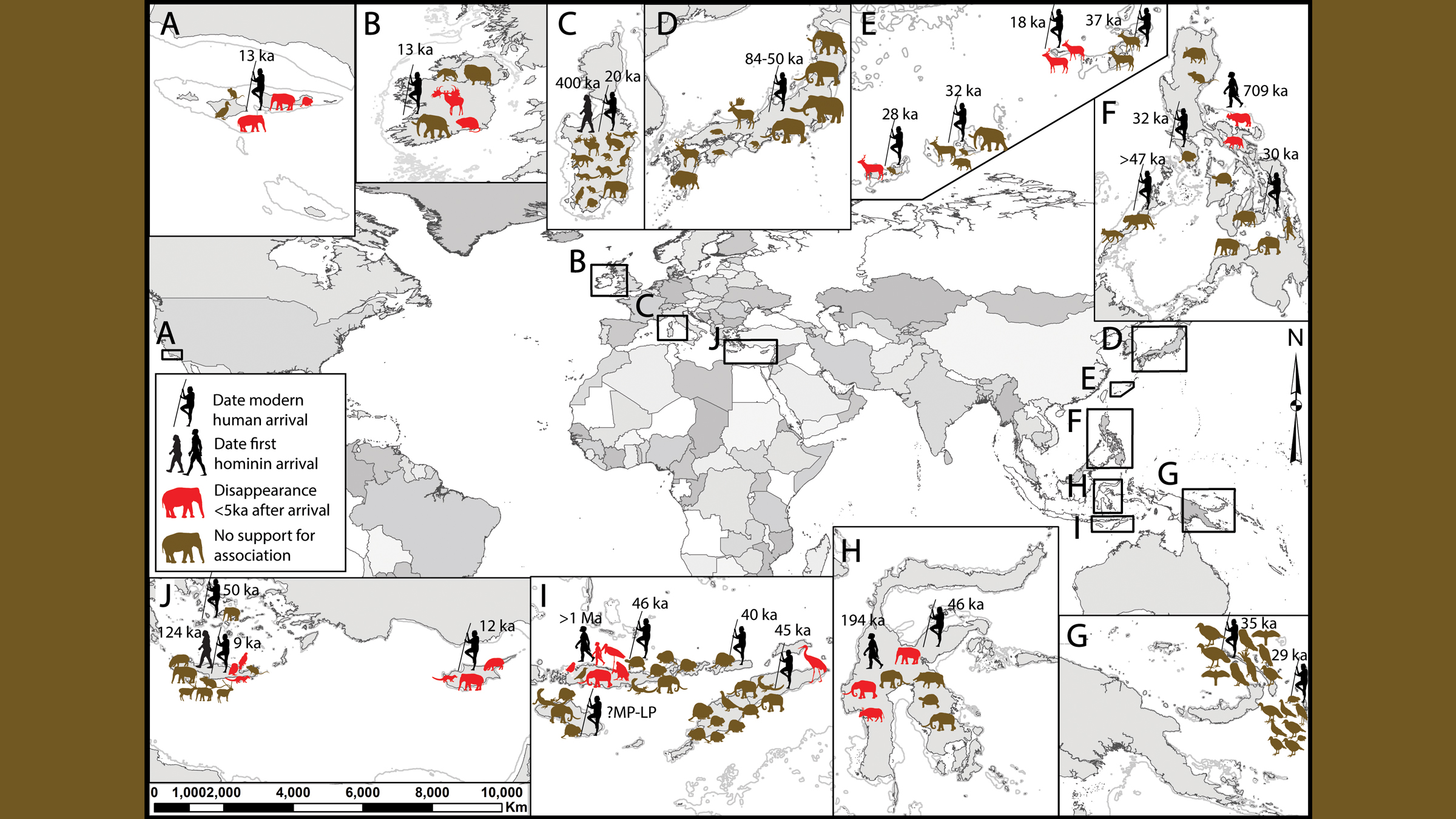

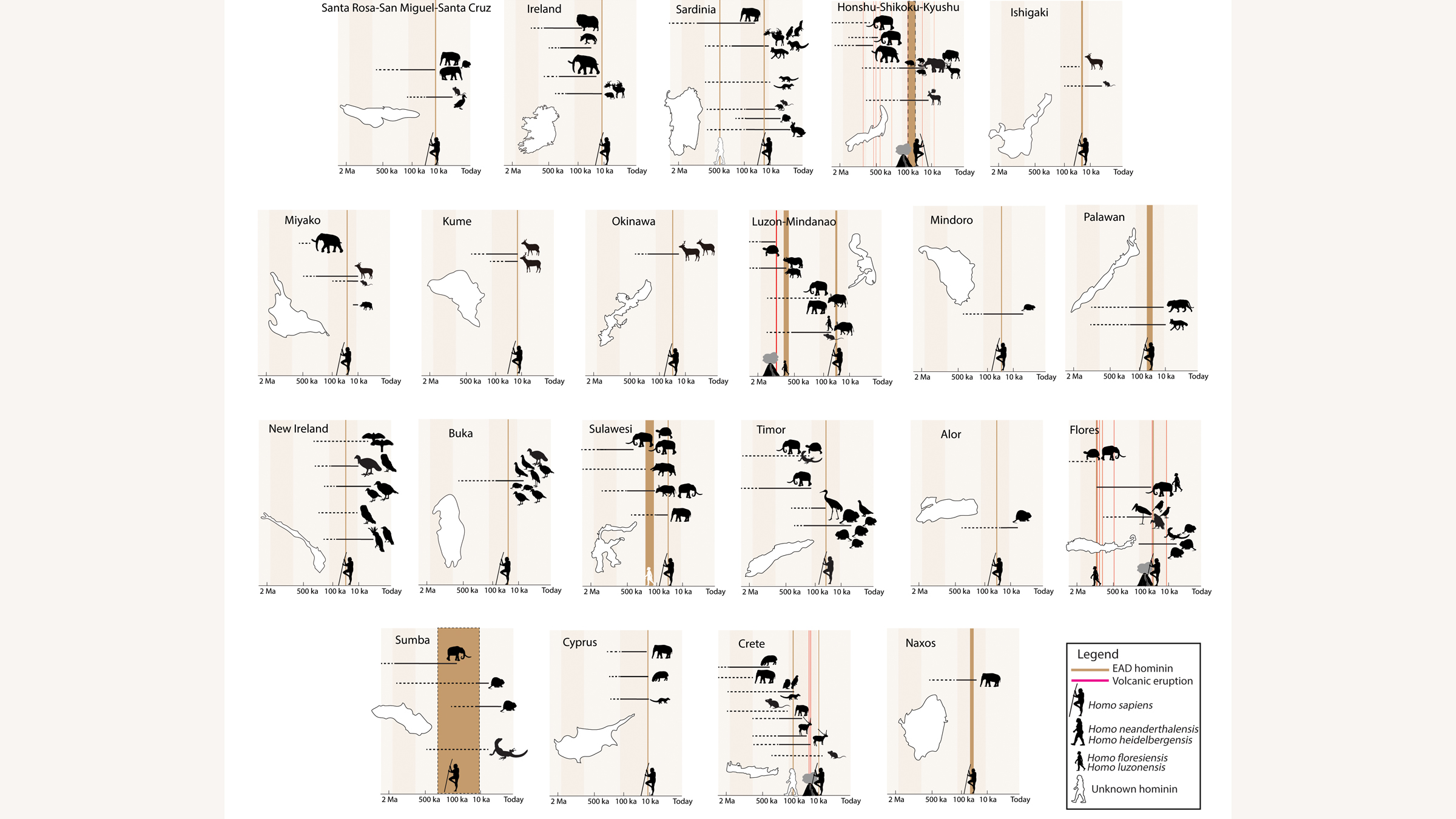

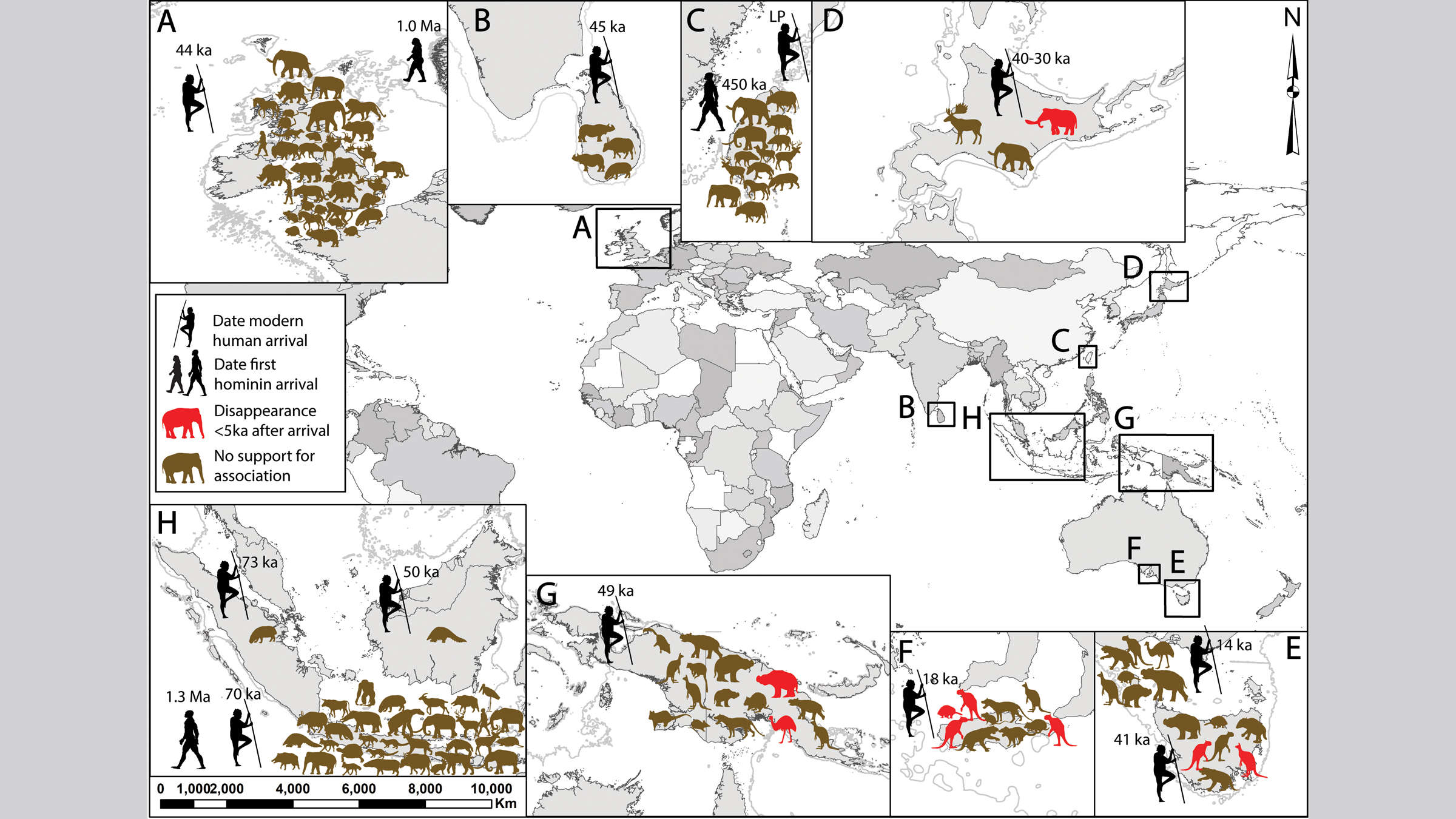

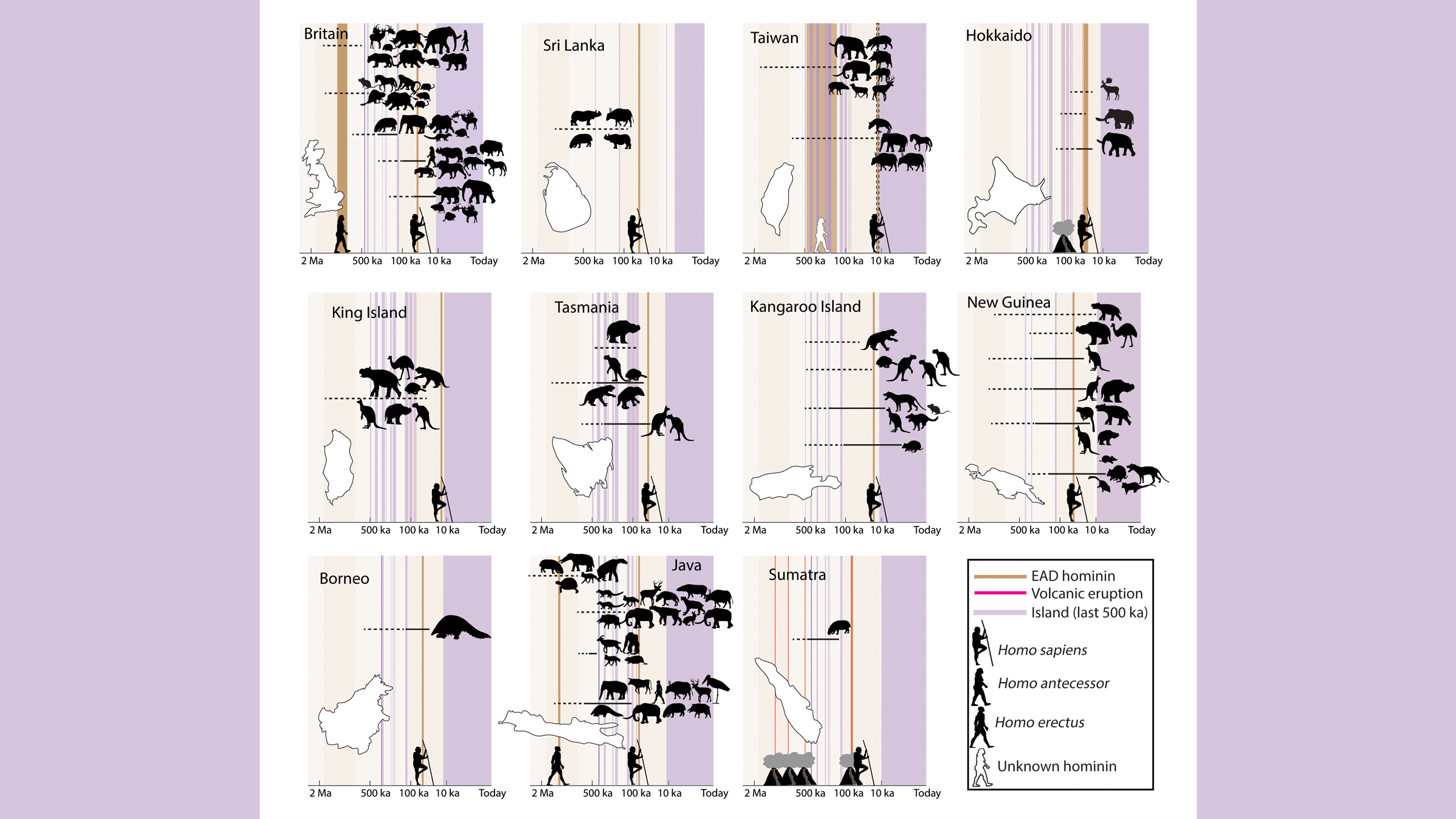

To investigate whether island extinctions coincided with the arrival of hominins — or modern humans, our ancestors and our close evolutionary cousins — the researchers dug into the archaeological and fossil record of 32 island groups that had evidence of a hominin presence, including Britain, Taiwan, Okinawa and Tasmania. (Unlike the group hominids, the hominin group doesn't include orangutans.) However, dating hominin arrival and island extinctions wasn't always easy, MacPhee said. Moreover, it was difficult to disentangle whether an animal went extinct largely because of humans or due to other factors, such as climate change, he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"However, the places where we acquired most of our data — island archipelagos to the east of the Asian mainland — were less affected by serious detectable climate change of the kind that affected North America" at the end of the last ice age, when large animals such as the mammoth went extinct, he said.

The team also accounted for the fact that some extinctions happen naturally throughout evolution. Moreover, they cite evidence that early hominins hunted land animals — after all, there are ancient animal bones with butcher marks on them. But early hominins didn't hunt creatures into oblivion, the team found. "Instead, there was coexistence, just as there is [in] nature all the time among different species," MacPhee said. "Again and again, evidence showed that "these earlier versions of ourselves ... did not raise extinction rates on the islands they colonized."

For example, on Flores in Indonesia, where the "Hobbits," or Homo floresiensis, lived, "there are no known extinctions closely associated with the first hominin appearance," the researchers wrote in the study. The same is true of hominins in Sardinia, they found.

Related: Gallery: Mystery of the pygmy elephants of Borneo

In contrast, within 5,000 years of modern humans arriving on the California Channel Islands about 13,000 years ago, the Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbia), the pygmy mammoth (Mammuthus exilis) and a vole (Microtus miguelensis) went extinct, the researchers found. Likewise, in Ireland, a giant deer (Megaloceros giganteus) and a lemming (Dicrostonyx torquatus) went extinct soon after modern humans arrived 13,000 years ago, as was the case for a crane (genus Grus) that disappeared in the Southeastern Asian country of Timor after modern humans arrived 46,000 years ago.

The list goes on: an elephant in Sulawesi, Indonesia; a stork (Leptoptilos robustus), vulture (genus Trigonoceps), songbird (genus Acridotheres), elephant-like stegodon (Stegodon florensis insularis) and even Homo floresiensis, which disappeared soon after the arrival of Homo sapiens on Flores, the researchers found.

Why are modern humans jerks?

So, why are modern humans such drivers of extinctions, and early hominins aren't?

"Culture, culture, culture," MacPhee said. "If you see human adaptation through the lens of culture, then the clearest distinction between then and now is the degree to which we can nowadays control environments planetwide."

In other words, early hominins had little control over their environments; they could hunt, but it was technologically unsophisticated. "Early people on islands got there in most cases by making sea journeys — they were already oriented toward the sea and marine resources, and either did not know how to hunt land animals or were not interested in doing so," MacPhee said.

As people became more advanced, it's likely that "our behavior toward environments changed and became more destructive as we became more technologically able," MacPhee said.

The finding shows that people shouldn't assume that "our ancestors were pre-loaded with the same will to overexploit that we have, that it is somehow in our genes," he said. "If there is a lesson, then it is simply this: Act like our distant ancestors did, take what you need from nature but do not destroy it in the process."

This also explains why extinctions weren't linked with the first arrivals of Homo sapiens on islands about 50,000 years ago. "It appears that during this time, both hominins and island faunas occurred and flourished together," said Julian Hume, a paleontologist and research associate with the National History Museum, London, in the United Kingdom who wasn't involved with the study. At that time, there were fewer people, less sophisticated tools and a slower colonization rate, he said. This changed during the Holocene, when modern humans mastered long-distance overseas movement in large numbers, developed sophisticated tools and brought nonnative animals with them to islands.

Related: In images: Wacky animals that lived on Mauritius

Hume noted, however, that islands are notoriously poor preservers of fossils. In addition, fossils that persist through time tend to be from large and robust, rather than small and delicate, animals. So, it's hard to say, looking at the fossil record, whether earlier hominins did or didn't cause animal extinctions, he told Live Science in an email.

What's more, ancient burnt and butchered animal bones are "surprisingly rare," Hume said. "Because the authors have found little evidence of human predation, does not mean that it did not take place."

But Hume still agreed with the researchers' takeaway message. "We can understand, and perhaps forgive, those human ancestors that hunted for necessity as they traveled across the oceans," Hume said. "What is unforgivable is that modern humans are destroying the natural world at an unprecedented speed, despite having detailed knowledge of what the ultimate price will be."

The study was published online Monday (May 3) in the journal the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.