Why celebrate Earth Day? Here are 12 reasons.

12 scientists share amazing facts about Earth for Earth Day's 50th anniversary.

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of Earth Day, Live Science asked a dozen scientists to share their favorite facts about our home planet. These researchers marveled at everything from backward flowing rivers in Antarctica to the Giant Crystal Cave of Naica in Mexico, which one geologist called the "Sistine Chapel of crystals."

Read on to learn about Earth's wonders. If you've got one of your own to share, write about it in the comments below.

1. Mountainous changes

"The top of Mount Everest is limestone from an ancient ocean floor formed 470 million years ago — before life had even left the ocean! I love this fact, because it reminds us of the tremendous changes our Earth has gone through to bring us to this moment in time, from mass extinctions to asteroid impacts and vast movements of the very ground we stand on. Just as humans are one small speck in a vast universe (thanks, Carl Sagan!), so too are we a tiny blip of time in the long arc of Earth's history," said Jacquelyn Gill, an associate professor in the School of Biology and Ecology and the Climate Change Institute at the University of Maine.

That fact can be sobering, but it provides a message of hope for our species as well.

"When we lose species because of our actions, we're cutting threads in a tapestry that has taken billions of years to weave, and it records stories of vulnerability and loss, but of survival and resilience, too."

So while our planet's past may provide warnings of upheavals, it can also provide hints for charting the future.

"The clues to surviving global change are in the rocks, for those who can read them," Gill said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

2. Giant Crystals of Naica

Juan Manuel García-Ruiz, a geologist at the Spanish National Research Council, has spent a good portion of his career crawling into underground vaults of pure crystal. Last year, García-Ruiz authored a paper on the history of the largest geode on Earth — a jagged, crystal chamber in a Spanish mine that can comfortably fit several scientists inside at once. But his favorite spot on Earth is where the Giant Crystal Cave of Naica lays buried, about 1,000 feet (300 meters) below the town of Naica, Mexico.

"This is the 'Sistine Chapel of crystals,'" García-Ruiz told Live Science. Giant gypsum pillars, most of which are as large and thick as telephone poles, slash through the basketball-court-size cavern in a brilliant display of Earth's slow-motion alchemy. The crystals are hundreds of thousands of years old, and still actively growing in the hot, humid cave. For now, the largest one measures 39 feet (12 m) in length and 13 feet (4 m) in diameter, and it weighs 55 tons (50 metric tons).

3. Earth's mysterious synergy

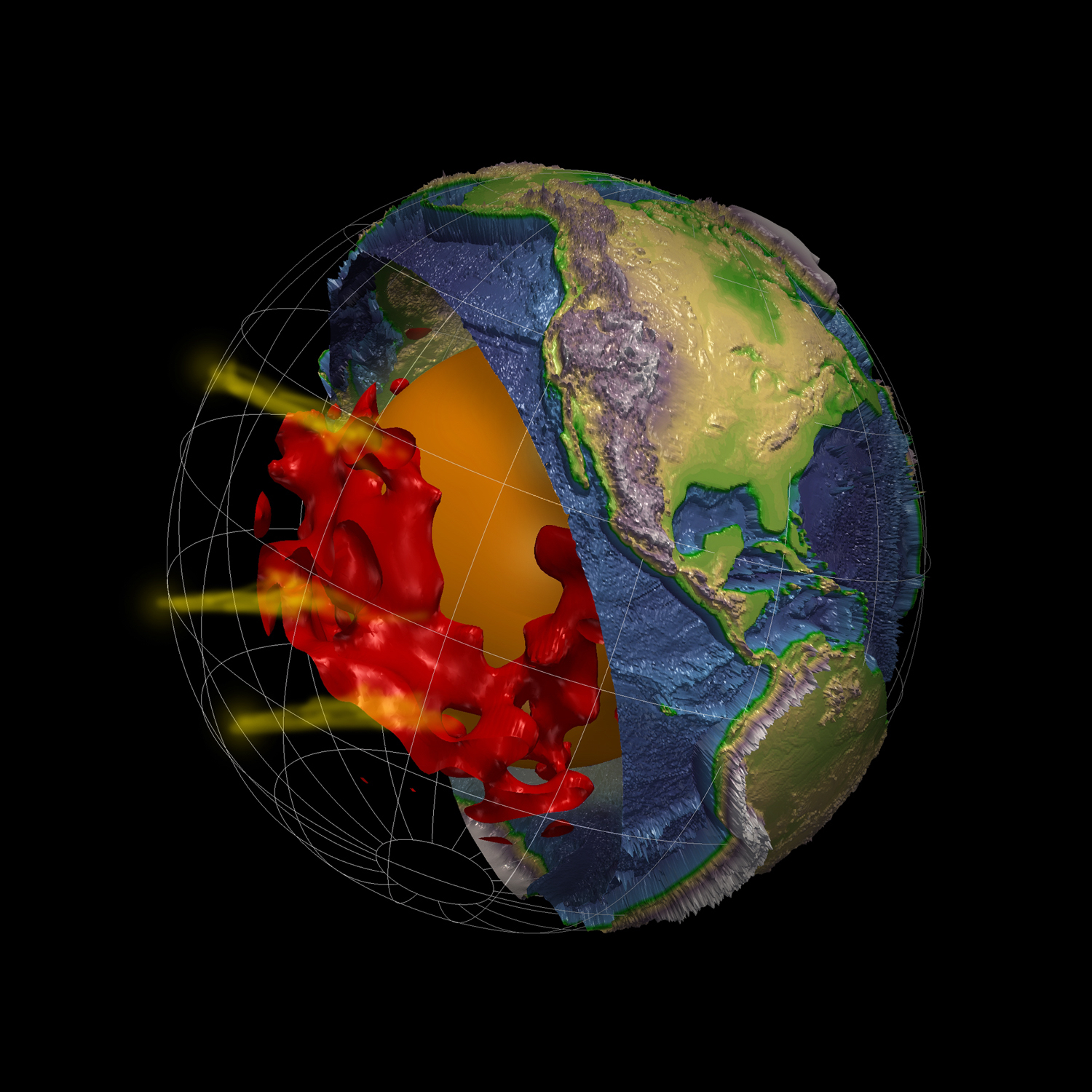

"My favorite fact about Earth is that all parts of it, from the center to the atmosphere, appear to be dynamically and chemically interactive, over a wide range of time scales and spatial scales," Ed Garnero, a professor at Arizona State University's School of Earth and Space Exploration, told Live Science.

As an example of this planet-wide synchronicity, Garnero sent an image (which he made) depicting the mysterious underground structures that some researchers have labeled "the blobs." These lopsided, continent-sized mountains sit inside Earth's mantle about halfway between your feet and the center of the planet. While scientists know from seismic imaging that these blobs exist, nobody is exactly sure what they are or what they do.

One intriguing feature of the structures, Garnero said, is that plumes of exceptionally hot rock (depicted here in yellow) appear to rise off the blobs and feed certain volcanoes on the surface — essentially creating a chemical pipeline that connects the deep Earth to the high atmosphere.

"I guess an addendum to this fact is that there is SO MUCH that we do not know about Earth — from the internal structures to the climate," Garnero said. "It is an exciting time to monitor, measure and model the observations."

4. "Stained glass" diatoms

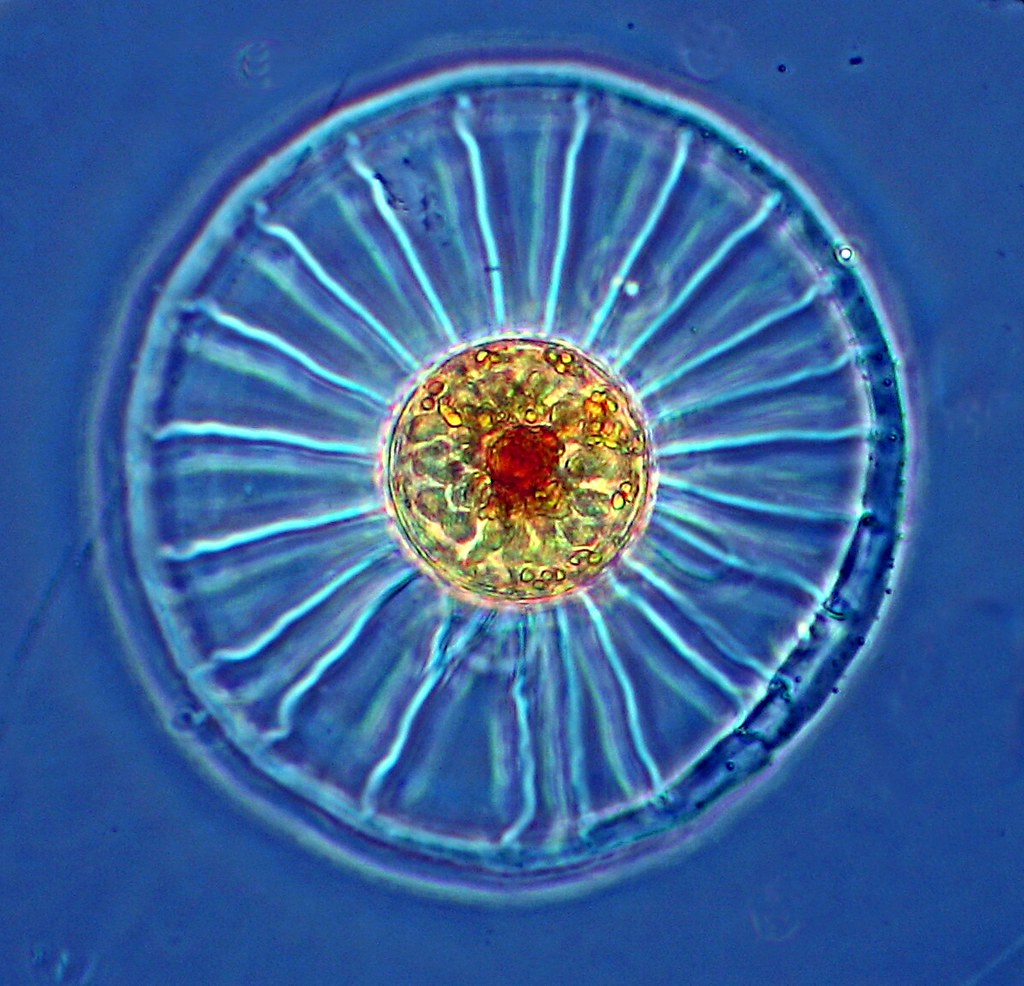

One of the most amazing facts about Earth is that "around 20-50% of the Earth's oxygen is produced by diatoms," said Sarah Webb, a biologist and associate professor of life science at Arkansas State University-Newport.

"Diatoms are microscopic algae with a shell made of glass," Webb told Live Science in an email. Diatoms are pretty to look at, too, she said. "They look like stained glass when viewed under a microscope."

Life as we know it wouldn't be around were it not for an abundance of lung-friendly oxygen gas in our atmosphere. Earth has been oxygenated for about 2.3 billion to 2.4 billion years, but the tiny, delicate diatoms of today likely evolved around 250 million years ago. These unicellular organisms are ubiquitous in Earth's oceans, and scientists estimate that there are more than 100,000 species of diatoms.

5. Rivers that flow backward

Antarctica, Earth's southernmost continent, is one of the driest places on the planet. But there's a surprising amount of liquid water lurking below the continent's frozen surface that doesn't behave as you might expect.

"Beneath the ice in Antarctica there are mountain ranges where rivers flow backward and lakes [that are] the size of New Jersey," said Robin Bell, president of the American Geophysical Union and a professor at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University in Palisades, New York.

"The weight of the overlying ice makes the water flow backward while the heat of the Earth keeps the water in the subglacial rivers and lakes from turning into ice," Bell said.

Scientists discovered clues to a backward-flowing river in Antarctica's Gamburtsev Mountains after they examined the shape of the icy layer atop the hidden river; that layer aligned with the direction of the water's movement.

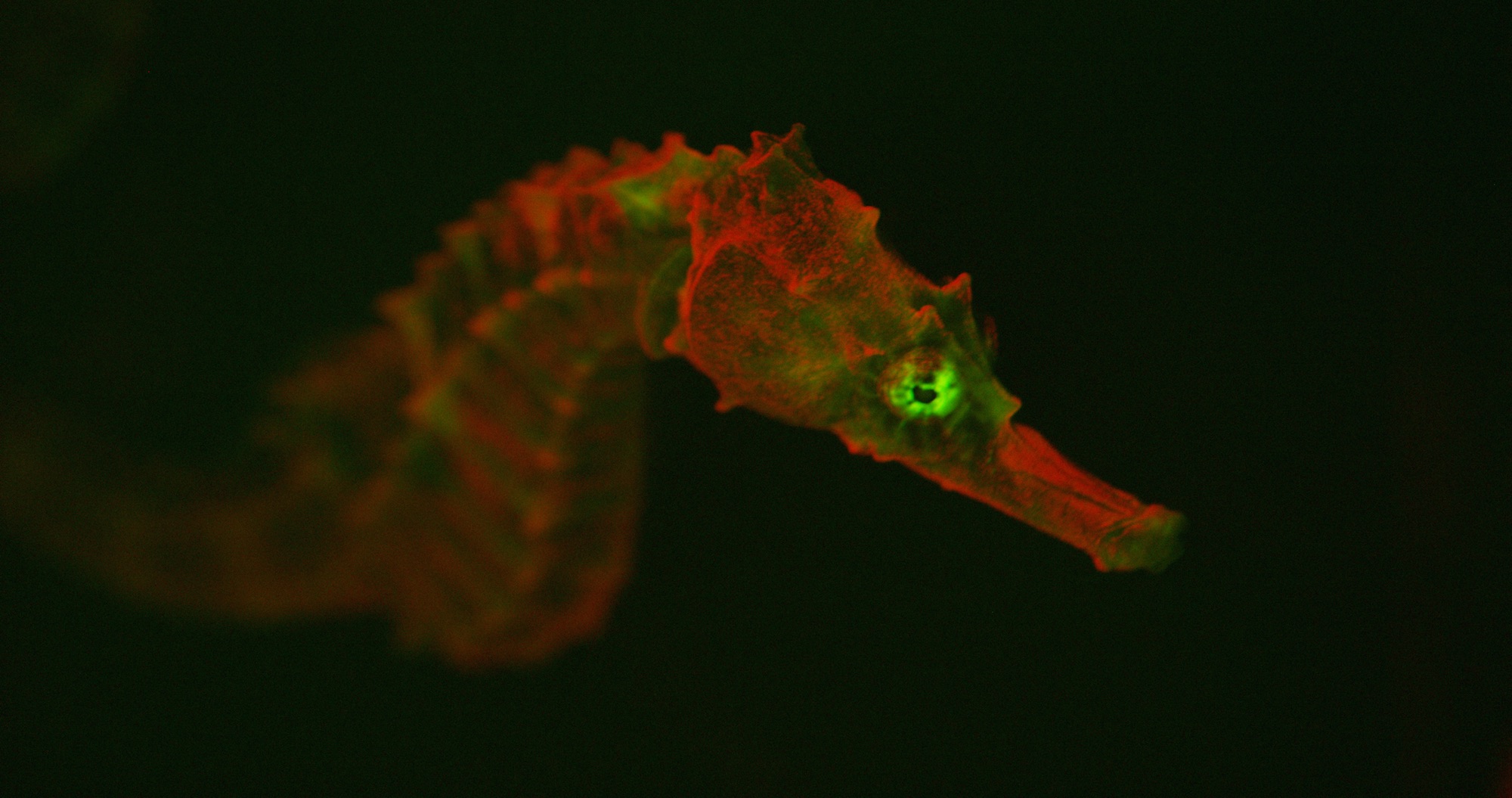

6. Glowing sea creatures

More than 70% of Earth is covered with water, so it's no surprise that scientists such as David Gruber find inspiration in exploring these great depths. Gruber, a presidential professor of biology at City University of New York and an explorer with the National Geographic Society, studies glowing marine animals. He snapped the above photo, which shows the first biofluorescent seahorse known to science.

"Knowing how much magic is happening beneath the sea that we've yet to even learn about yet," is Gruber's favorite Earth fact. "It's perhaps my main inspiration as a scientist that maintains my child-like curiosity."

There's so much to learn. "How we are connected to other life and what our place is on this amazing planet is still in its early stages," Gruber told Live Science.

7. Route 66

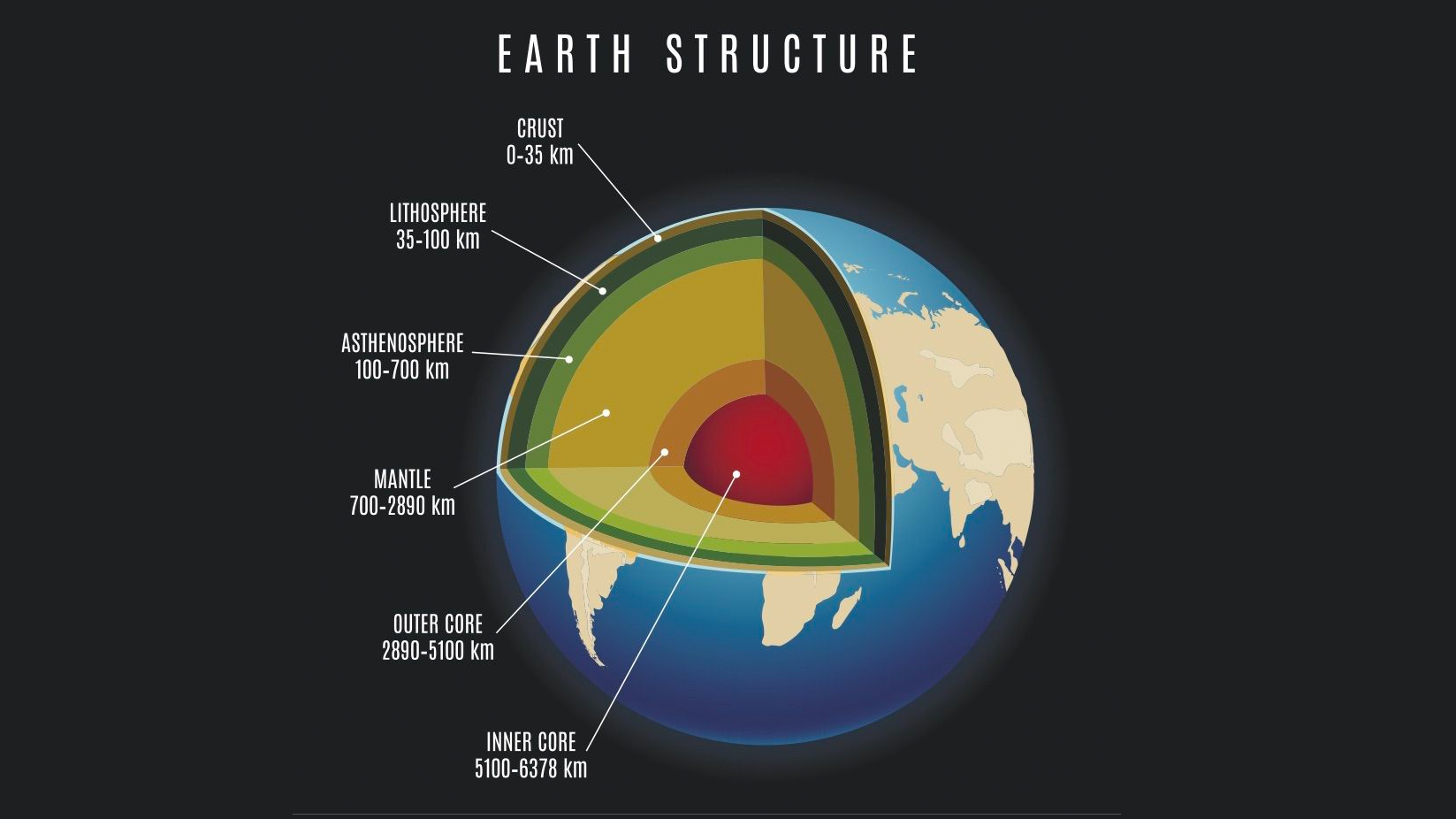

"The boundary between Earth’s mantle and core is roughly 3,000 km [about 1,865 miles] below our feet, a little less than the total length of America’s 'Mother Road,' Route 66," said Jennifer Jackson, a professor of Mineral Physics at Caltech.

Initially, researchers thought that this region was a simple interface between solid rocks and liquid iron-rich metal. But, in reality, "this remote region is almost as complex as Earth’s surface," she said.

While it's impossible to reach this Route-66-long place in person, "geophysical and experimental studies of this distant region reveal a fascinating landscape of chemical and structural complexity that influences what's happening on Earth’s surface," Jackson said. "For example, the complex dynamics of Earth’s core-mantle boundary affects Earth’s protective geomagnetic field and the motion of tectonic plates."

8. Life on our planet

Our planet harbors magnificent life-forms, from tiny, near-invisible organisms to giant, ferocious beasts. Billions of years ago, conditions became just right for the tiniest particles to combine together and form the very first life-forms.

These life-forms are nearly as ancient as Earth itself. "The Earth is over 4.6 billion years [old], and life has been present on the Earth continuously since at least 3.5 billion years ago," Shuhai Xiao, professor of geobiology in the Department of Geosciences at Virginia Tech. The earliest evidence for life on our planet comes from the marks these organisms left on rocks, according to a previous Live Science report.

Photosynthetic organisms called cyanobacteria were some of the earliest life-forms on our planet. Here is a photo of fossilized Cambrian mounds formed by cyanobacteria in Newfoundland, Canada.

9. Climate feedback

Another amazing feature of our planet is how various processes interact in so-called negative climate feedbacks, which act to dampen temperature changes if they get too extreme, meaning too cold or too hot, said Jonathan Overpeck, dean of the School for Environment and Sustainability at the University of Michigan. (In general, "feedbacks" occur when one process causes a change in a second process, which in turn influences the first.)

"It’s amazing how [negative] climate feedbacks have maintained a habitable planetary climate for hundreds of millions of years — right in the sweet spot of not too cold, not too warm," said Jonathan Overpeck, dean of the School for Environment and Sustainability at the University of Michigan.

On the other hand, processes known as "positive" feedbacks can make the effects of climate change worse, because they may further amplify the planet's already increasing temperatures, according to NASA.

"We need to fight climate change harder, to keep our planet habitable and flourishing," Overpeck said. "That’s what we all need to rededicate ourselves to on this 50th anniversary of the first Earth Day."

10. The past influences the future

An amazing fact is that "historical legacies often dictate how Earth will respond to modern change," said Merritt Turetsky, the director of the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research at the University of Colorado Boulder.

"A legacy can be thought of as [a] memory of an ecosystem with regard to past events," Turetsky said. "One example is permafrost, frozen soils that have accumulated at high latitudes over millennia. Today, permafrost soils store so much carbon — derived from ancient plants, animals and microbes that existed on the surface of our planet — that they will be a major player in how Earth responds to future climate change."

"The past often is the key to understanding our planet's future," Turetsky told Live Science.

Caption: Merritt Turetsky's team samples frozen permafrost soils in Alaska and Canada to understand how past soil types influence the ability of Arctic ecosystems to cope with modern environmental change.

11. Fascinating dimensions

Our planet is a dynamic and ever-evolving giant orb, with earthquakes shifting the rocky plates that make up its surface, volcanoes that exude fiery lava from the planet's innards, and even deep-sea hydrothermal vents that gurgle out sizzling mineral water that supports bizarre forms of life. All of this can be enchanting to scientists who immerse themselves in the planet's geology.

Glacial geologist Johann Philipp Klages said his favorite aspects of Earth are "its fascinating dimensions and unexpected forces, which pleasantly tell us, again and again, how small and insignificant we are in the context of Earth's history."

Klages is a research scientist in the Marine Geology section of the Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Center for Polar and Marine Research in Bremerhaven, Germany. An expedition on the institution's icebreaker RV Polarstern took Klages to the Amundsen Sea Embayment in West Antarctica in 2017, where he captured this gorgeous image of the ship in front of the Pine Island ice shelf edge.

12. Natural healing

What is Earth's greatest feature? That "it supports life!" Marcia Macedo, an associate scientist and director of the Water Program at Woods Hole Research Center (WHRC) in Massachusetts, told Live Science.

"What amazes me is that most natural systems have the capacity to heal themselves after big disturbances," she said. "This is as true for a human body recovering from disease as it is for a tropical forest growing back after an intense fire."

Macedo added, "sometimes that healing is facilitated by surprising heroes," such as the tapir, which can restore degraded forests in the Amazon. The tapir does this by munching on fruit from healthy trees and then depositing their seeds in areas that have been previously burned, according to a WHRC statement and a recent webinar presentation by Macedo.

Editor's note: This caption of fact nine was updated at 11:15 am E.DT. to note that the animal is an elk, not a moose. Also, fact nine was fixed to clarify the difference between negative and positive climate feedback.

- Earth pictures: Iconic images of Earth from space

- Earth from above: 101 stunning images from orbit

- Earth Day: Our favorite photos of the planet

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'How It Works' 'All About Space' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.