Most of Earth's carbon may be locked in our planet's outer core

The discovery could help explain the discrepancy in Earth's core density.

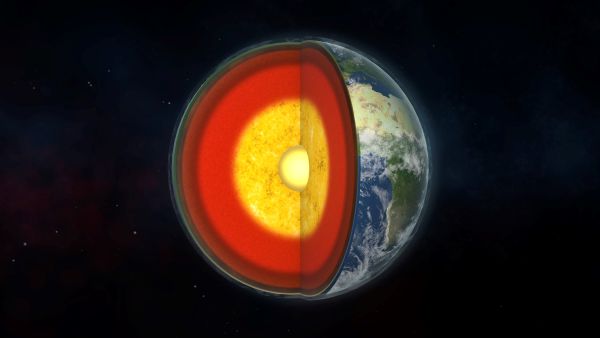

The liquid outer core of Earth might be the largest reservoir of carbon on the planet.

The percentage sounds small, somewhere between 0.3% and 3%, but once you take into account the size of the outer core (1,355 miles (2,180 kilometers) thick) it equates to a colossal quantity of carbon — somewhere between 5.5 and 36.8 yottagrams. (That's the number followed by 24 zeros!)

This carbon estimate could help solve the mystery surrounding the density of Earth's core, scientists said.

Related: 4.5 billion-year-old particles from the sun lurk in Earth's core and mantle

"Understanding the composition of the Earth's core is one of the key problems in the solid-earth sciences," study co-author Mainak Mookherjee, an associate professor of geology in the Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science at Florida State University, said in a statement. "We know the planet's core is largely iron, but the density of iron is greater than that of the core.

The scientists believe there must be lighter elements — such as carbon — in the core that reduce its density.

According to the researchers, this is not the first time scientists have attempted to quantify the amount of carbon in the outer core. But it is the first study to refine the carbon estimate range by taking into account other light elements — such as oxygen, sulfur, silicon, hydrogen and nitrogen — to estimate Earth's outer core composition.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Studying Earth's core is no mean feat as it lies about 4,000 miles (6,400 km) beneath our feet, far beyond the realms of direct measurements. Instead, scientists use compressional sound waves and computer models to analyze the chemical makeup of the outer core.

In the new study, scientists compared the speed of compressional sound waves moving through the Earth to computer models that simulated different amounts of iron, carbon and other light elements in order to find the best match.

"When the velocity of the sound waves in our simulations matched the observed velocity of sound waves traveling through the Earth, we knew the simulations were matching the actual chemical composition of the outer core," study lead author Suraj Bajgain, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science at Florida State University, said in the same statement.

This new study narrows down the range of estimated carbon content on Earth to be between 990 parts per million and more than 6,400 parts per million. The researchers suggest that between 93% and 95% of this carbon is found in the core (both inner core and outer core), making it a significant carbon reservoir.

Understanding how much of this life-essential element exists on Earth will help scientists improve their understanding of the composition of both our planet and rocky planets elsewhere in the universe, according to the researchers.

"It's a natural question to ask where did this carbon that we are all made of come from and how much carbon was originally supplied when the Earth formed," Mookherjee said. "Where is the bulk of the carbon residing now? How has it been residing and how has it transferred between different reservoirs? Understanding the total inventory of carbon is what this study gives us insight to."

The research is described in a study published Aug. 19 in the journal Communications Earth and Environment.

You can follow Daisy Dobrijevic on Twitter at @DaisyDobrijevic. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Daisy Dobrijevic joined Space.com in February 2022 as a reference writer having previously worked for our sister publication All About Space magazine as a staff writer. Before joining us, Daisy completed an editorial internship with the BBC Sky at Night Magazine and worked at the National Space Centre in Leicester, U.K., where she enjoyed communicating space science to the public. In 2021, Daisy completed a PhD in plant physiology and also holds a Master's in Environmental Science, she is currently based in Nottingham, U.K.