Earth tipped on its side (and back again) in 'cosmic yo-yo' 84 million years ago

The planet would've looked a little weird.

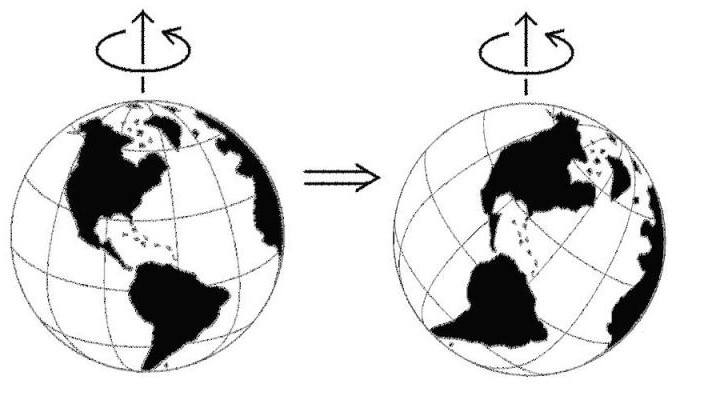

Earth has not always been upright. Turns out, the planet's crust tipped on its side and back again around 84 million years ago, in a phenomenon that researchers have dubbed a "cosmic yo-yo."

The actual name for the tipping is true polar wander (TPW), which occurs when the outer layers of a planet or moon move around its core, tilting the crust relative to the object's axis. Some researchers had previously predicted that TPW occurred on Earth late in the Cretaceous period, between 145 million and 66 million years ago, but that was hotly debated, according to a statement by the researchers.

However, the new study strongly suggests TPW did occur on Earth. Researchers mapped the ancient movement of Earth's crust by looking at magnetic-field data trapped inside ancient fossilized bacteria. They found that the planet tilted 12 degrees relative to its axis around 84 million years ago, before fully returning to its original position over the next 5 million years.

Related: 10 out-of-this-world images of Earth taken by Landsat satellites

"This observation represents the most recent large-scale TPW documented and challenges the notion that the [Earth's] spin axis has been largely stable over the past 100 million years," the researchers wrote in their paper, published online June 15 in the journal Nature Communications.

Cosmic yo-yo

Earth is made out of four main layers: the solid inner core, the liquid outer core, the mantle and the crust. During TPW, the entire planet would appear turned over on its side, but in reality only the outermost layers have moved.

"Imagine looking at Earth from space, TPW would look like the Earth tipping on its side," co-author Joe Kirschvink, a geobiologist at the Tokyo Institute of Technology in Japan and a professor at the California Institute of Technology, said in the statement. "What's actually happening is that the whole rocky shell of the planet [the mantle and crust] is rotating around the liquid outer core."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Individual pieces of Earth's outermost layers are constantly moving and changing as tectonic plates collide together and subduct underneath one another; but during TPW, the outer layers move together as a single unit.

As a result, the tilt in Earth's crust would not have resulted in any major tectonic activity or drastic changes to major ecosystems. Instead, it would have been a gradual process that would not have impacted the dinosaurs and other living things walking around on the surface.

Earth's electromagnetic field would have been static during the TPW because it is created by the liquid inner core, which would have stayed in place. So rather than the magnetic poles moving, it is the geographic poles that start to wander.

Fossilized magnets

To test if Earth did undergo TPW during the Cretaceous, the researchers turned to magnetic minerals within limestone deposits in Italy.

"These Italian sedimentary rocks turn out to be special and very reliable because the magnetic minerals are actually fossils of bacteria that formed chains of the mineral magnetite," co-author Sarah Slotznick, a geobiologist at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, said in the statement.

Magnetite is a highly magnetic form of iron-oxide. Some types of bacteria can create chains of tiny magnetite crystals, which naturally orient with Earth's magnetic field at the time of their creation. When these particular bacteria died and were fossilized during the period of TPW, these magnetite chains got locked in place.

Because Earth's crust moved during TPW, and not its magnetic field, these magnetic fossils (which remained in surface layers of the planet) revealed how much the crust moved relative to Earth's magnetic field over time. The team found that Earth's crust moved a total of almost 25 degrees over a period of 5 million years.

The researchers believe that their findings now settle the question of whether Earth had a TPW during the Cretaceous.

"It is so refreshing to see this study with its abundant and beautiful paleomagnetic data," Richard Gordon, a geophysicist at Rice University in Houston who was not involved in the study, said in the statement.

Originally published on Live Science.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.