Earth's mantle has a gooey layer we never knew about

While the mantle is mostly solid, a layer about 93 miles (150 kilometers) down is melty, new research finds.

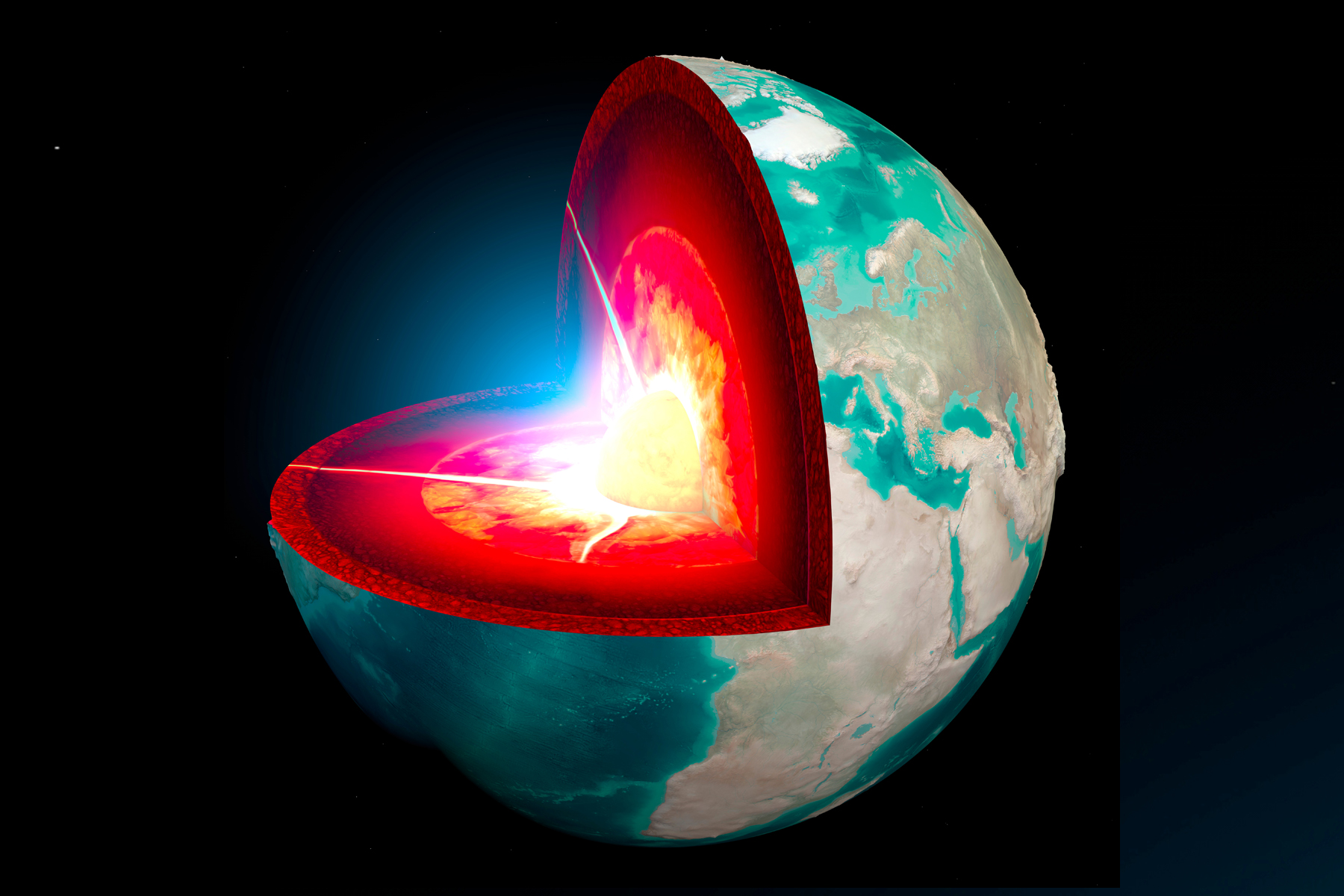

Most of Earth's mantle is hot but solid, with rocks that deform slowly rather than cracking like the cooler rocks of the crust do. But new research finds that around 93 miles (150 kilometers) below Earth's surface, there is a worldwide layer of melted rock.

Discovering this gooey layer will help researchers better understand how the tectonic plates "float" on top of this mantle layer, study first author Junlin Hua, a postdoctoral researcher in geosciences at the University of Texas at Austin, told Live Science.

The melted rock is in the asthenosphere, the upper layer of the mantle that sits between about 50 miles (80 km) and 124 miles (200 km) below Earth's surface. The only way to peer into this layer of the mantle is with seismic waves from earthquakes. Researchers can detect the waves at seismic stations set up around the world, looking for subtle changes in the waveforms that indicate what kinds of materials the waves traveled through. Previously, researchers knew from these types of studies that some parts of the asthenosphere were hotter than others, Hua said, and patchy areas of melt had been detected. But little was known about how deep and widespread the melt was.

To find out, Hua and his colleagues collected data from thousands of seismic waves detected at 716 stations around the world. They found that rather than holding small areas of melt, the asthenosphere appears to contain a partially melted layer that extends around the globe, under at least 44% of the planet. This area is broadly distributed across the globe and could be much larger, the researchers found, because they were unable to probe under the ocean, which is likely to overlay a layer of melt and which takes up much more area than the continents.

Oddly, though, this melted layer doesn't seem to affect the movements of the tectonic plates. The researchers found that the areas of melt did not affect the mantle's viscosity, or tendency to flow.

"[That] melted rock in addition to solid rock is not much easier to be deformed than those solid rocks alone," Hua said. "So counterintuitively, those melts, though present, won't affect how easily tectonic plates can move above the asthenosphere."

This is useful information for building computer models of how the plates move, the study co-authors said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We can't rule out that locally melt doesn't matter," Thorsten Becker, a geophysicist at UT Austin and one of the authors of the study, said in a statement. "But I think it drives us to see these observations of melt as a marker of what's going on in the Earth, and not necessarily an active contribution to anything."

There is still more work to be done to map out this melty mantle layer, however, Hua said.

"In this study, we are mainly using seismic instruments on continents, and though we have also used some instruments from ocean islands, there are certainly some degrees of data gap in the ocean," he said. "Hence, a nice follow-up study would be using other types of data or seismic instruments located on ocean bottoms to bridge this gap."

The researchers published their findings Feb. 6 in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.