Why does electricity make a humming noise?

Is it ever a sign of danger?

You may have heard it when flipping on a light, switching on your TV or walking near power lines — that unmistakable hum of electricity. But what, exactly, is that hum? And more important, is it ever a sign of danger?

The sound electricity makes is known as the "mains hum," and it happens because of the way electricity is produced. The electricity that comes from power plants uses alternating current (AC), so named because the current changes direction, or alternates, many times per second.

The number of times per second the current alternates depends on the standard of the particular country. In places such as the United States, Canada and several Central and South American countries, AC power alternates at 60 hertz, or 60 times per second. In much of the rest of the world, it alternates at 50 hertz, or 50 times per second.

Related: Why do some fruits and vegetables conduct electricity?

The hum you hear is usually about twice the frequency of the AC power being used, according to Gary Woods, a professor in the practice in the electrical and computer and engineering department at Rice University in Texas. That means that in the U.S., electricity hums at 120 hertz, or between a B and B-flat two octaves below middle C. In Europe, it hums at 100 hertz, or between an A-flat and G two octaves below middle C.

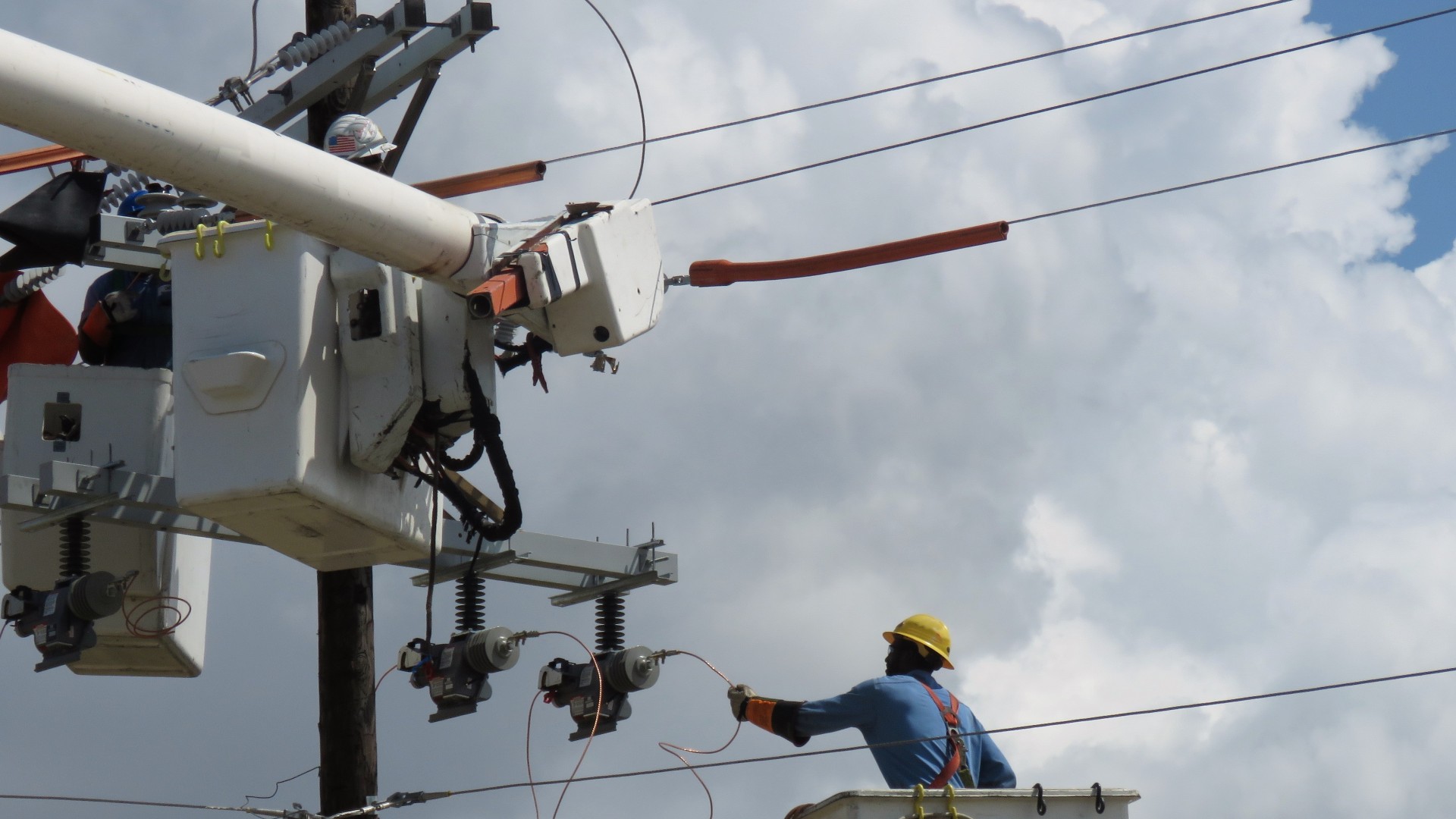

But what, exactly, is vibrating to create that hum? It's usually a magnetic element inside the device. For example, when you're near power lines, you might hear an electric hum coming from an electromagnetic device called a transformer, which is used to decrease the voltage of the power as it travels from the power plant to people's homes, so the high voltage from the power plant doesn't overload household electronics.

"A transformer has an inductor inside it, which is just a magnetic element — it's an electromagnet," Woods told Live Science. "It's a piece of iron that has a coil of wire wrapped around it. That's inside every transformer.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"For reasons of electrical engineering, you need to have an electromagnet inside the electronics to get the function that you want," Woods told Live Science. "And so you can think of these magnetic elements as being like little magnets, and they're being energized by the electric power. And so they're turning on and off [reversing their polarity] 60 times a second. So they're actually vibrating a little bit."

The same thing happens in all sorts of electronics, from fluorescent bulbs to toaster ovens, Woods said.

The reason power lines themselves might hum is due to a different phenomenon called corona discharge. This hum, or discharge of energy, happens when the electrical field around the power lines is greater than what is needed to start a flow of electric current from the power line to the surrounding air. The likelihood of that happening can depend on the weather, as water increases the conductivity of air. Most modern power lines are designed to avoid this problem, at least during dry conditions. If corona discharge does occur, it can be dangerous; there's evidence that corona discharge can produce toxic gases like ozone, which can harm human lungs if inhaled.

But is the mains hum in your electronics a sign of danger?

"Probably danger is too strong a word," Woods said. That hum is usually just a normal part of how electronics function. But sometimes, it could be the telltale sign that something is wrong.

"If it never hummed before and suddenly it starts to hum and it gets louder and louder, that probably means that there's some element inside the device that's about to fail," Woods said.

"The air conditioning unit in my home one time, it started making a 60-hertz hum," Woods said. "So I called the air conditioner repairman, and they said, 'No, it's nothing.' And I said, 'Well, no, I know a 60-hertz hum when I hear it. There's something wrong.' And so they came out, and sure enough, there was a bad component inside it," Woods said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Ashley Hamer is a contributing writer for Live Science who has written about everything from space and quantum physics to health and psychology. She's the host of the podcast Taboo Science and the former host of Curiosity Daily from Discovery. She has also written for the YouTube channels SciShow and It's Okay to Be Smart. With a master's degree in jazz saxophone from the University of North Texas, Ashley has an unconventional background that gives her science writing a unique perspective and an outsider's point of view.