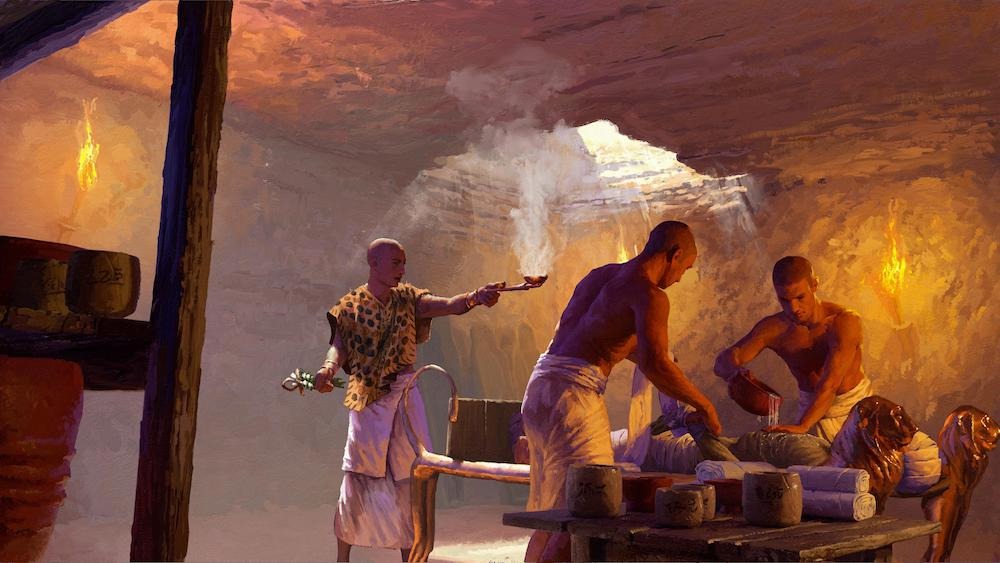

Elaborate underground embalming workshop discovered at Saqqara

A workshop discovered in Saqqara showcases the different ingredients ancient Egyptians used for embalming.

Archaeologists at Saqqara have finally identified the many embalming ingredients used to mummify the dead in ancient Egypt. They also deciphered how those different ingredients — many of which came from distant lands — were used.

In 2016, an international team of archaeologists discovered the underground embalming workshop near the pyramid of Unas, south of Cairo. The complex of rooms held approximately 100 ceramic vessels dating to the 26th dynasty of Egypt (664 to 525 B.C.). While many of the vessels had inscriptions identifying their contents, some of the embalming substances remained a mystery.

Now, in a first-of-its-kind study published Feb. 1 in the journal Nature, researchers have used chemical analysis of the resins coating the vessels to identify the contents.

Upon closer examination, the researchers discovered that certain vessels were labeled with embalming instructions such as "to put on the head" or "bandage/embalm with it," while others included the names of the different substances found inside, according to a statement.

But by analyzing the residues coating the pottery, they identified ingredients on 31 of the vessels coming from locations near and far. Those included resin from the elemi tree (Canarium luzonicum), which is native to the Philippines; resin from Pistacia, a genus of flowering plants in the cashew family that grow in parts of Africa and Eurasia; and beeswax.

Related: Ancient Egyptian mummification was never intended to preserve bodies, new exhibit reveals

The facility's layout revealed the meticulousness of the embalmers, with "one room being used to clean the bodies and the other for storage [and for the actual embalming]," study co-author Susanne Beck, a lecturer in the Department of Egyptology at the University of Tübingen in Germany, said during a news conference (Jan. 31).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the researchers compared the different identified mixtures with the inscriptions on the labels, they found several inaccuracies. For one, the ancient Egyptian word "antiu," which translates to "myrrh" or "incense," was often mislabeled. In fact, none of the analyzed residues represented a single substance but rather a blend of multiple ingredients, according to the statement.

"We were able to identify the true chemical makeup of each substance," study co-author Philipp Stockhammer, professor in the Department of Archaeogenetics at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, said during the conference. "Often [embalming vessels become contaminated over time], but in this case they're not. A lot of the vessels in this case were in good condition."

However, not all of the contents found in the workshop were used to preserve the dead. Instead, they likely "helped remove unpleasant smells" and prepared the bodies for embalming by "reducing moisture on the skin," study lead author Maxime Rageot, an assistant lecturer in archaeological science at the University of Tübingen, said during the news conference.

"It's fascinating the chemical knowledge [the embalmers] had, since they knew bare skin would immediately be endangered by microbes," Stockhammer said. "They knew what substances were antifungal and could be applied to help stop the spread of bacteria on the skin."

Most surprising was that embalmers relied on elaborate trade networks that crisscrossed the globe to source ingredients not native to the region.

"[We were] surprised to find tropical resins," Stockhammer said. "This shows that the industry of embalming was a driving trade and that ingredients were transported from large distances. What we're learning goes far beyond what we know about embalming."

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.