Enormous 'polar vortex' on the sun is unprecedented, scientists say

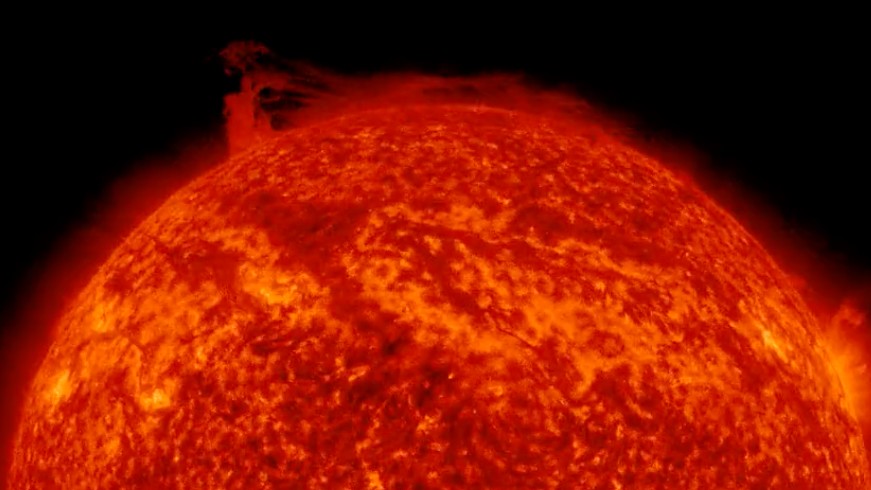

A long, looping filament of plasma snapped over the sun's north pole, creating a 'polar vortex' that scientists can't explain.

On Feb. 2, a massive tentacle of plasma snapped apart in the sun's atmosphere before tumbling down, circling the star's north pole at thousands of miles a minute, and then disappearing — leaving scientists baffled.

The entire spectacle, which lasted about 8 hours, went viral on Twitter when Tamitha Skov, a science communicator and research scientist at The Aerospace Corporation in California, posted footage of the event captured by NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory.

"Talk about Polar Vortex!" Skov tweeted. "Material from a northern prominence just broke away from the main filament and is now circulating in a massive polar vortex around the north pole of our Star."

Talk about Polar Vortex! Material from a northern prominence just broke away from the main filament & is now circulating in a massive polar vortex around the north pole of our Star. Implications for understanding the Sun's atmospheric dynamics above 55° here cannot be overstated! pic.twitter.com/1SKhunaXvPFebruary 2, 2023

What does this all mean? Essentially, a long filament of plasma — the electrically charged gas that all stars are made of — shot out of the sun's surface, creating a huge looping feature called a prominence. These structures are common and can loop into space for hundreds of thousands of miles as solar plasma spirals along tangled magnetic field lines.

What is strange, however, is for a prominence to suddenly break apart and then remain airborne for hours, swirling around the sun's poles. As Skov and other researchers have remarked, the resulting cyclone of plasma resembled a polar vortex — a type of low-pressure system that forms large loops of frigid air over Earth's poles in winter.

Scott McIntosh, a solar physicist and deputy director at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, told Live Science's sister site Space.com that he has never seen solar plasma behave this way before. However, McIntosh added, long filaments do regularly erupt near the sun's 55-degree latitude lines, where the odd prominence was spotted.

Filaments like these appear more commonly as the sun's 11-year activity cycle ramps up toward the solar maximum, the sun's period of peak magnetic activity. During the solar maximum, the sun's magnetic field lines tangle and snap with high frequency, creating lots of sunspots and belching large streams of plasma far into space. The next solar maximum is predicted to begin in 2025, and solar activity has clearly been on the rise in the past several months.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

On their own, plasma filaments pose no threat to Earth. However, erupting filaments can lead to the release of enormous, fast-moving blobs of plasma and magnetic fields called coronal mass ejections (CMEs), according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Space Weather Prediction Center. If one of these electrically charged blobs happens to pass over Earth, it can damage satellites, trigger widespread power-grid failures and push colorful auroras to be visible at much lower latitudes than usual.

Fortunately, the Feb. 2 filament was not pointed at Earth and did not release a CME. Still, more research is needed to figure out exactly how and why this rare solar vortex formed — and what consequences, if any, could result, McIntosh said.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.