The virus behind 'mono' might trigger multiple sclerosis in some

Scientists have long suspected a link between Epstein-Barr virus and multiple sclerosis.

Multiple sclerosis — an autoimmune disease that affects the brain and spinal cord — may emerge after infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

An estimated 90% to 95% of people catch EBV, also called human herpesvirus 4, by the time they reach adulthood, according to the clinical resource UpToDate. In children, the virus typically causes an asymptomatic or very mild infection, but in teens and young adults, EBV can cause infectious mononucleosis, better known as "mono." Despite EBV being a commonly-caught virus, there's evidence to suggest that infections with the virus are a risk factor for multiple sclerosis, a far less common condition.

Studies have shown, for example, that people with multiple sclerosis have remarkably high levels of EBV-specific antibodies — immune molecules that latch onto the virus — compared with those without the disease. And prior research hinted that catching mono raises the risk of developing multiple sclerosis later in life. Given that most people catch EBV at some point, however, it's been difficult to demonstrate that these infections may actually be an underlying cause of multiple sclerosis.

Related: Going viral: 6 new findings about viruses

Now, a new study, published Thursday (Jan. 13) in the journal Science, provides evidence for this idea. By combing through data from about 10 million U.S. military members, collected over the course of two decades, the research team found that the risk of developing multiple sclerosis increases 32-fold following an infection with EBV. They found no such link between the autoimmune disease and other viral infections, and no other risk factors show such a high increase in risk.

The study shows that EBV is clearly associated with the development of multiple sclerosis, while other viruses are not, said Dr. Lawrence Steinman, a professor of neurology and neurological sciences at Stanford University School of Medicine, who was not involved in the study. One limitation of the research is that it does not explain exactly how EBV might drive the disease — but other recent work provides strong clues, Steinman told Live Science in an email.

'Compelling evidence'

"We've been working on this hypothesis, that EBV may be a causal risk factor for MS, for about 20 years," said Kassandra Munger, a co-senior author of the Science study and senior research scientist in the Neuroepidemiology Research Group at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. To test this hypothesis, the team set out to identify individuals who had never been exposed to the virus, track their EBV status through time and see if their chance of developing multiple sclerosis increased following exposure.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Again, "this is a challenging hypothesis to test because over 95% of the population is infected with EBV by adulthood," Munger noted. So to identify people with no prior EBV exposure, the team combed through a unique dataset curated by the U.S. Department of Defense.

The Department of Defense maintains a repository of serum, the yellowish, fluid portion of blood, sampled from military personnel. At the start of their service, and about every two years afterward, active-duty military members provide serum for HIV screening, and any residual serum from the tests gets placed in the repository. Serum contains antibodies, and thus, these stored samples provided the researchers with a way to check each person's EBV status through time, by checking for antibodies against the virus.

The team then used this data to investigate the potential link between EBV status and the onset of multiple sclerosis. (Of course, their data only focused on these individuals who became exposed in their early 20s, rather than during childhood.)

Using medical records, they identified 801 individuals who developed multiple sclerosis during the study period and who had provided at least three serum samples prior to their diagnosis. They found that 35 of these 801 individuals had tested negative for EBV-specific antibodies at their initial serum sampling, but in time, all but one person became exposed to the virus. So 800 out of the 801 caught EBV before developing multiple sclerosis.

The team ran several tests to see if any other viruses shared such a strong correlation with the disease, but found EBV was the only one to stand out in this way.

Related: 11 surprising facts about the immune system

And the team spotted another hint that EBV triggers multiple sclerosis: In the serum of those who developed the disease, the team spotted signs of nerve damage that showed up after their EBV exposure but before their official MS diagnosis.

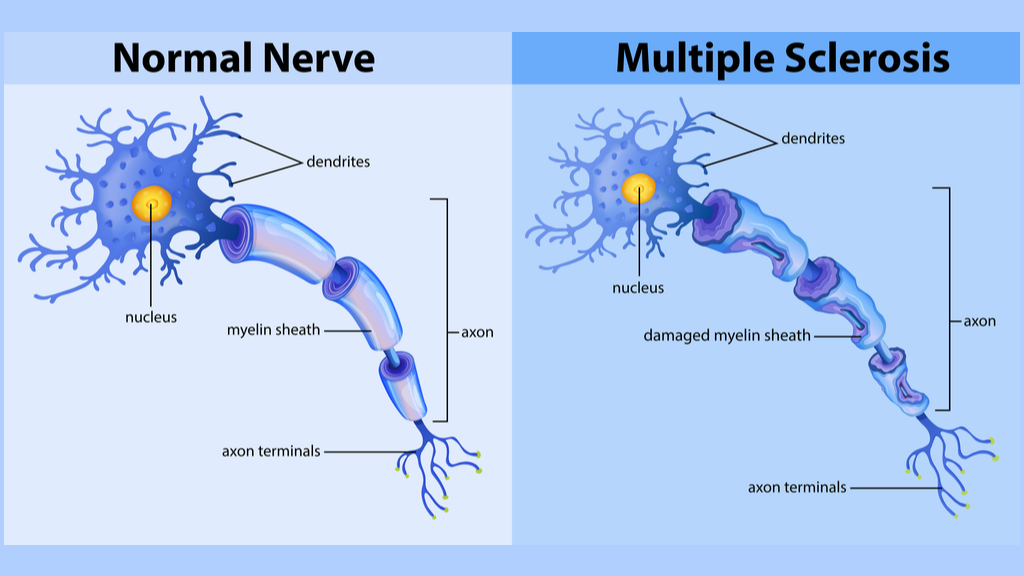

In multiple sclerosis, the immune system mistakenly attacks myelin, an insulating sheath that surrounds many nerve fibers, and this damage impairs the ability of nerve cells to transmit signals. Early signs of this nerve cell damage can appear up to six years prior to the onset of multiple sclerosis, according to a 2019 report in the journal JAMA; so the team looked for hints of this damage in the serum samples.

Specifically, they looked for a protein called neurofilament light chain, whose concentrations go up in the blood following damage to nerve cells. This protein increased in the serum of those who went on to develop multiple sclerosis, but only after they became exposed to EBV. For those in the control group, who never developed multiple sclerosis, the concentration of neurofilament light chain in their blood remained the same before and after they caught EBV; this aligns with the idea that EBV exposure doesn't jumpstart multiple sclerosis in everyone, but rather only in susceptible people. "The infection seems to occur prior to any evidence of nervous system involvement," Munger said.

Taken with the other study results, "this is really, we think, compelling evidence of causality," she told Live Science.

"It kind of inextricably links EBV infection and the development of MS," Robinson said, echoing the sentiment. That said, the work cannot reveal exactly why this link exists — but a recent study led by Robinson and Steinman provides some clues.

That study, posted Jan. 11 to the preprint database Research Square, has not yet been peer-reviewed or published in a scientific journal. It suggests that, in people with multiple sclerosis, specific antibody-producing cells appear in great numbers in the fluid surrounding the brain and spinal cord. These cells make antibodies that latch onto an EBV protein called EBNA-1 — but unfortunately, the same antibodies also go after a similar looking molecule on the cells that make myelin.

Several other studies also provide evidence of EBV-specific antibodies targeting components of nerve cells and the myelin sheath itself. "I think that that would be the leading hypothesis, that a viral component looks like a self protein," and that this striking similarity drives the immune system to attack myelin, Robinson said.

Of course, even with this mounting evidence, one big question remains: If most people catch EBV at some point, why do only some people go on to develop multiple sclerosis? The answer lies, at least in part, in their genes.

Evidence suggests that specific versions of genes that regulate the immune system may make a person susceptible to multiple sclerosis, Robinson said. Within that genetic context, EBV can then light the fuse that sets off the development of multiple sclerosis. But perhaps in the future, an EBV vaccine could prevent that fuse from ever being lit, or therapeutics could counter the virus's lingering effects on the immune system, thus stopping multiple sclerosis in its tracks, he said.

"Now that the initial trigger for MS has been identified, perhaps MS could be eradicated," Steinman and Robinson wrote in a commentary.

Originally published on Live Science.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Flu: Facts about seasonal influenza and bird flu

What is hantavirus? The rare but deadly respiratory illness spread by rodents