Seussian beast survived the Triassic by taking lots of naps

A new study suggests hibernation is an ancient adaptation to harsh winters.

Some 250 million years ago, a Seussian-looking beast with clawed digits, a turtle-like beak and two tusks may have survived Antarctica's chilly winters not by fruitlessly foraging for food, but by curling up into a sleep-like state, meaning it may be the oldest animal on record to hibernate, a new study finds.

Analysis of this Triassic vertebrate's ever-growing tusks revealed that it may have spent part of the year hibernating, a strategy that is still used by modern animals to tough out long winters. Like hibernators alive today, these ancient animals, who belong to the extinct genus Lystrosaurus, slowed down their metabolism and underwent periods of minimal activity when conditions got rough.

"Animals that live at or near the poles have always had to cope with the more extreme environments present there," lead study author Megan Whitney, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University, said in a statement. According to Whitney, who conducted the research as a University of Washington doctoral student of biology at the University of Washington, "these preliminary findings indicate that entering into a hibernation-like state is not a relatively new type of adaptation. It is an ancient one.”

Related: Image gallery: 25 amazing ancient beasts

Lystrosaurus, an ancient relative of mammals, could grow up to 8 feet (2.4 meters) long. The genus managed to survive the planet's largest mass extinction, which happened at the end of the Permian Period about 252 million years ago and killed 70% of land vertebrates. Lystrosaurus fossils have been found in India, China, Russia, Africa and Antarctica, according to the statement.

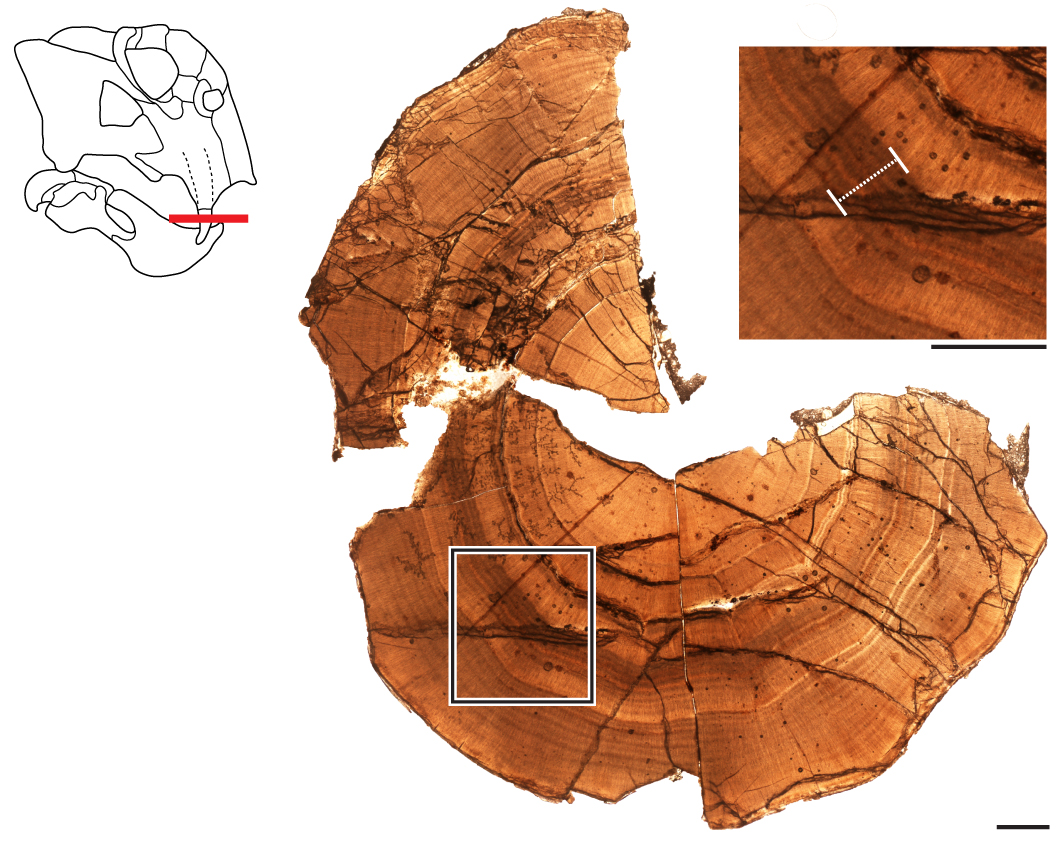

Two researchers from Harvard University and the University of Washington compared cross-sections (imagine slicing a tree trunk) of tusks from six Antarctic Lystrosaurus and four South African Lystrosaurus. The team found that the tusks from both regions had similar growth patterns made up of concentric circles of dentine, a hard, dense bony tissue. But the scientists also noted that the tusk fossils from Antarctica had some thick, closely-spaced rings that the fossils from South Africa did not.

These thicker rings represent less dentine deposition and suggest that the animals went through periods of prolonged stress, according to the statement.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The closest analog we can find to the 'stress marks' that we observed in Antarctic Lystrosaurus tusks are stress marks in teeth associated with hibernation in certain modern animals," Whitney said in the statement.

But it's not conclusive from the fossils if these animals truly went through hibernation, as the stress marks in their tusks could have been caused by a similar torpor, or period of decreased activity.

The findings also suggest that these strange, hairy, four-legged animals might have been warm-blooded, according to the statement. Cold-blooded animals often shut down their metabolisms completely during a hibernation season, but many warm-blooded animals frequently reactivate their metabolisms throughout the season, which is a pattern that the researchers observed in these ancient tusks.

At the time that these animals lived, the planet was much warmer and parts of Antarctica may have even harbored forests. Nevertheless, Antarctica still experienced the absence of the sun for long periods of time, so many other ancient vertebrates living at high altitudes likely also had to use torpor, Whitney said.

However, it's not easy for researchers to find evidence of torpor in extinct animals such as dinosaurs because these creatures didn't have teeth or tusks that grew throughout their lifetimes. And so, though their fossils are still found today, the narratives of their lives are often lost.

The findings were published Aug. 27 in the journal Communications Biology.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.