Giant worms terrorized the ancient seafloor from hidden death traps

Ancient worms built tunnels in the sea bottom, reinforcing the walls with mucus.

Gigantic predatory marine worms that lived about 20 million years ago ambushed their prey by leaping at them from underground tunnels in the sea bottom, new fossils from Taiwan reveal.

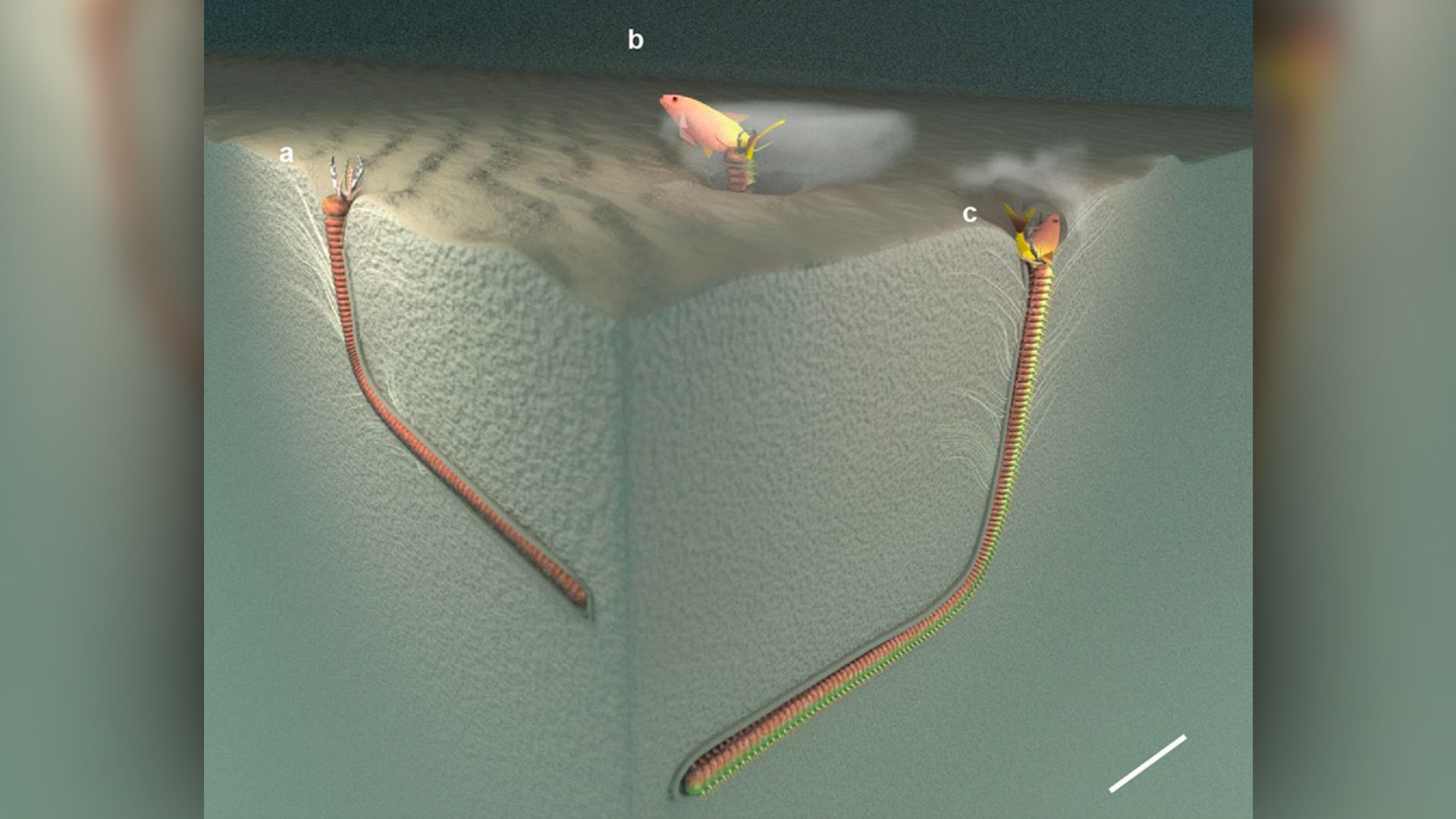

These monster worms may have been ancestors of trap-jawed modern Bobbit worms (Eunice aphroditois), which also hide in burrows under the ocean floor and can grow to be 10 feet (3 meters) long. Based on fossil evidence from Taiwan, the ancient worms' burrows were L-shaped and measured about 7 feet (2 m) long and 0.8 to 1.2 inches (2 to 3 centimeters) in diameter, researchers recently reported in a new study.

The soft bodies of such ancient worms are rarely preserved in the fossil record. But scientists found fossilized imprints, also known as trace fossils, left behind by the worms; some of these marks were likely made as they dragged prey to their doom. The researchers collected hundreds of these impressions to reconstruct the worm's tunnel, the earliest known trace fossil of an ambush predator, according to the study.

Related: These bizarre sea monsters once ruled the ocean

Bobbit worms are polychaetes, or bristle worms, which have been around since the early Cambrian period (about 543 million to 490 million years ago), and their hunting habits were swift and "spectacular," the scientists wrote. Modern Bobbit worms build long tunnels to accommodate their bodies; they hide inside and then lunge out to snap prey between their jaws, hauling the struggling creature into the subterranean lair for eating. This "terror from below" grasps and pierces its prey with sharp pincers — sometimes slicing them in half — then injects toxins to make prey easier to digest, according to Smithsonian Ocean.

Researchers examined 319 fossilized tunnel traces in northeastern Taiwan; from these traces, they reconstructed long, narrow burrows that resembled those made by long-bodied modern Bobbit worms. And preserved details in the rock further hinted at how ancient predatory worms might have used these lairs, according to the study.

"We hypothesize that about 20 million years ago, at the southeastern border of the Eurasian continent, ancient Bobbit worms colonized the seafloor waiting in ambush for a passing meal," the study authors reported. Worms "exploded" from their burrows when prey came close, "grabbing and dragging the prey down into the sediment. Beneath the seafloor, the desperate prey floundered to escape, leading to further disturbance of the sediment around the burrow opening," the scientists wrote.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As the ancient worms retreated deeper into their tunnel with the thrashing prey, the struggle agitated the sediment, forming "distinct feather-like collapse structures" that were preserved in the trace fossils. The researchers also detected iron-rich pockets in disturbed areas near the tops of the tunnels; these likely appeared after worms reinforced the damaged walls with layers of sticky mucus.

Though no fossilized remains of the worms were found, the scientists identified a new genus and species, Pennichnus formosae, to describe the ancient animals, based on their burrows' distinctive forms.

The likely behavior that created the tunnels "records a life and death struggle between predator and prey, and indirectly preserves evidence of [a] more diverse and robust paleo-ecosystem than can be interpreted from the fossil and trace fossil record alone," the study authors reported.

The findings were published online Jan. 21 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.