Extinct giant tortoise was the 'mammoth' of Madagascar 1,000 years ago

A previously unknown extinct tortoise was revealed in an investigation on these giants' evolutionary history.

At least a millennium ago, a giant tortoise crept through Madagascar, grazing on plants by the boatload — a bountiful diet that made it the ecosystem equivalent of mammoths and other big herbivores. And like the mammoth, this previously unknown giant tortoise is extinct, a new study finds.

The scientists discovered the species while studying the mysterious lineage of giant tortoises living on Madagascar and other islands in the western Indian Ocean. After stumbling across a single tibia (lower leg bone) of the extinct tortoise, they analyzed its nuclear and mitochondrial DNA and determined that the animal was a newfound species, which they named Astrochelys rogerbouri, according to the study, published on Jan. 11 in the journal Science Advances. The tortoise's species name honors the late Roger Bour (1947-2020), a French herpetologist and expert on western Indian Ocean giant tortoises.

It's unclear when the newfound species went extinct, but the specimen studied appears to be about 1,000 years old. "As we get better and better technology, we are able to provide different types of data that often change our perspective," study co-author Karen Samonds, an associate professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at Northern Illinois University, told Live Science. "It's really exciting to discover a new member of the community."

Related: This may be the biggest turtle that ever lived

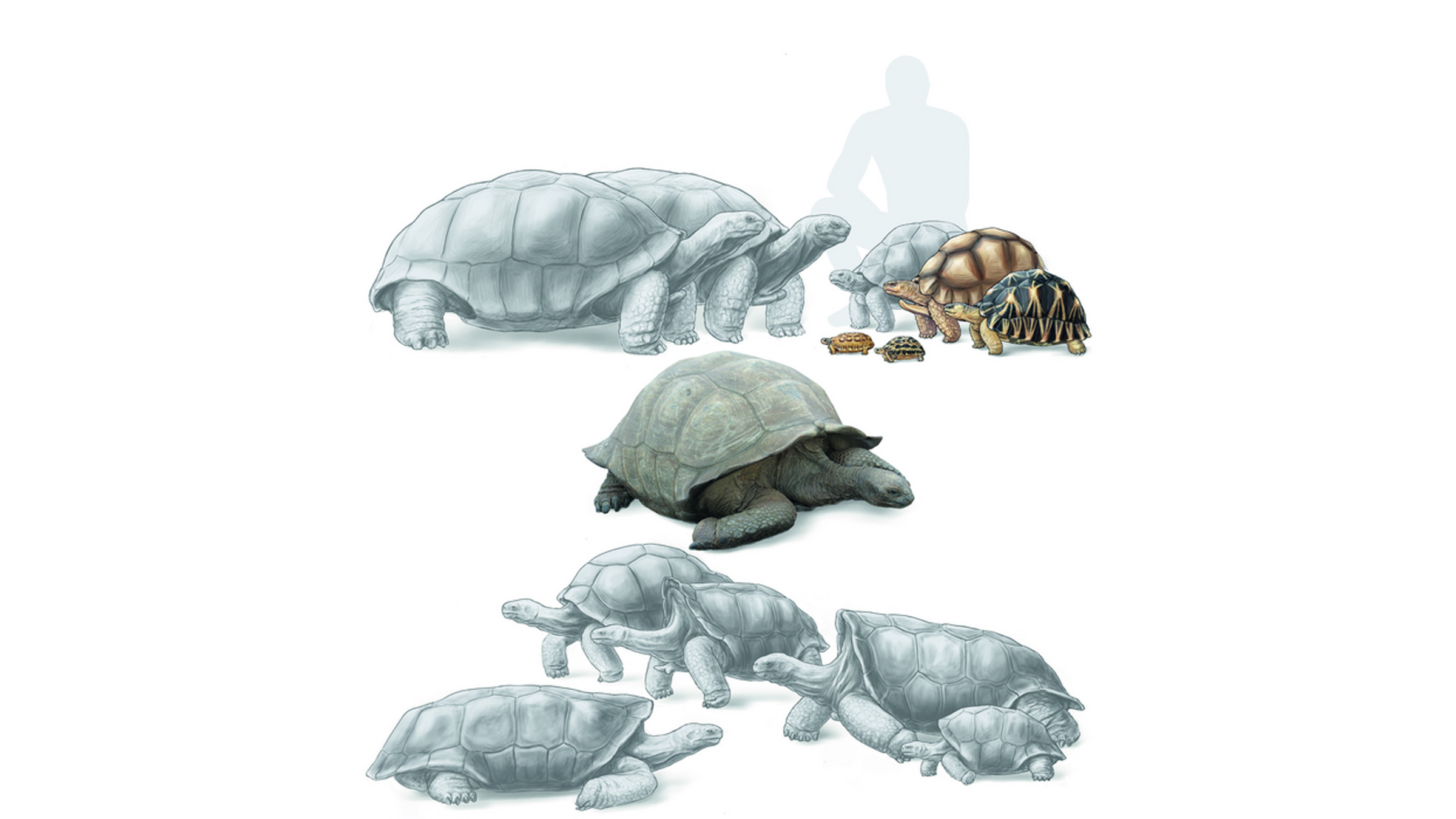

Volcanic islands and coralline atolls across the western Indian Ocean were once teeming with giant tortoises. Weighing up to 600 pounds (272 kilograms), these ponderous megafauna heavily influenced their ecosystems, if only through their voracious appetites. The 100,000 giant tortoises still living today on Aldabra — a verdant atoll northwest of Madagascar — consume 26 million pounds (11.8 million kg) of plant matter each year.

Most species native to that region are now extinct due to human activities, and paleontologists are still struggling to piece together the story of these bygone tortoises. But analyzing these giants' ancient DNA is providing a path forward, which, in turn, sheds light on prehistoric island life.

"If we want to know what these island ecosystems were like originally, we need to include giant tortoises — large, extinct members of the ecosystem which took on the role often occupied by large grazing mammals," Samonds said. "And in order to understand the key role they played, we need to understand how many tortoises there were, where they lived, and how they got there."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By the time explorers began collecting giant tortoise fossils in the 17th century, Madagascar's native giant tortoise population population had long since vanished — likely victims of colonization by the Indo-Malay people 1,000 years earlier — and their relatives plodding the Mascarene archipelago and the Granitic Seychelles were living on borrowed time. European sailors harvested the tortoises for food and "turtle oil," and all but those native to far-flung Aldabra were gone by the 19th century.

The tricky task of reconstructing their history would fall to modern paleontologists. "Tortoise remains are notoriously fragmented, and it's a real challenge to figure out what a tortoise looked like just from part of a shell," Samonds said. Scientists also struggled to make sense of a fossil record muddied by the tortoise trade. Had a particular specimen found in the Mascarene originated there, or was its carcass dropped off by a ship inbound from the Granitic Seychelles?

"In the end, a lot of these fossils sat in a cabinet, unused and unstudied," Samonds said. But recent technological advances in ancient DNA analysis granted Samonds and colleagues a glimpse inside the black box of tortoise evolutionary history. "It's thrilling that we now have this technology and can use ancient DNA to put these broken fossil pieces to good use."

For the study, Samonds and colleagues generated nearly complete mitochondrial genomes from several tortoise fossils, some of which were hundreds of years old. By combining these sequences with prior data on tortoise lineage and radiocarbon dating, the team was able to describe how giant tortoises migrated to various Indian Ocean islands.

The extinct Mascarene Cylindraspis lineage, for instance, appears to have left Africa in the late Eocene, more than 33 million years ago, and taken up residence on the now-sunken Réunion volcanic hotspot. From there, the species spread around local islands, resulting in the divergence of five Mascarene tortoise species between 4 million and 27 million years ago.

Samonds hopes future paleontological studies will follow the present work's example and benefit from incorporating ancient DNA analyses into more conventional methodologies.

"Including ancient DNA allowed us to examine how many tortoise species there were and what their relationships were to each other. It also helped us appreciate the original diversity of tortoises on these islands," Samonds said. "We couldn't have explored these topics before."

Joshua A. Krisch is a freelance science writer. He is particularly interested in biology and biomedical sciences, but he has covered technology, environmental issues, space, mathematics, and health policy, and he is interested in anything that could plausibly be defined as science. Joshua studied biology at Yeshiva University, and later completed graduate work in health sciences at Cornell University and science journalism at New York University.