This 130 million-year-old ichthyosaur was a 'hypercarnivore' with knife-like teeth

The ichthyosaur had evolved to chomp large prey.

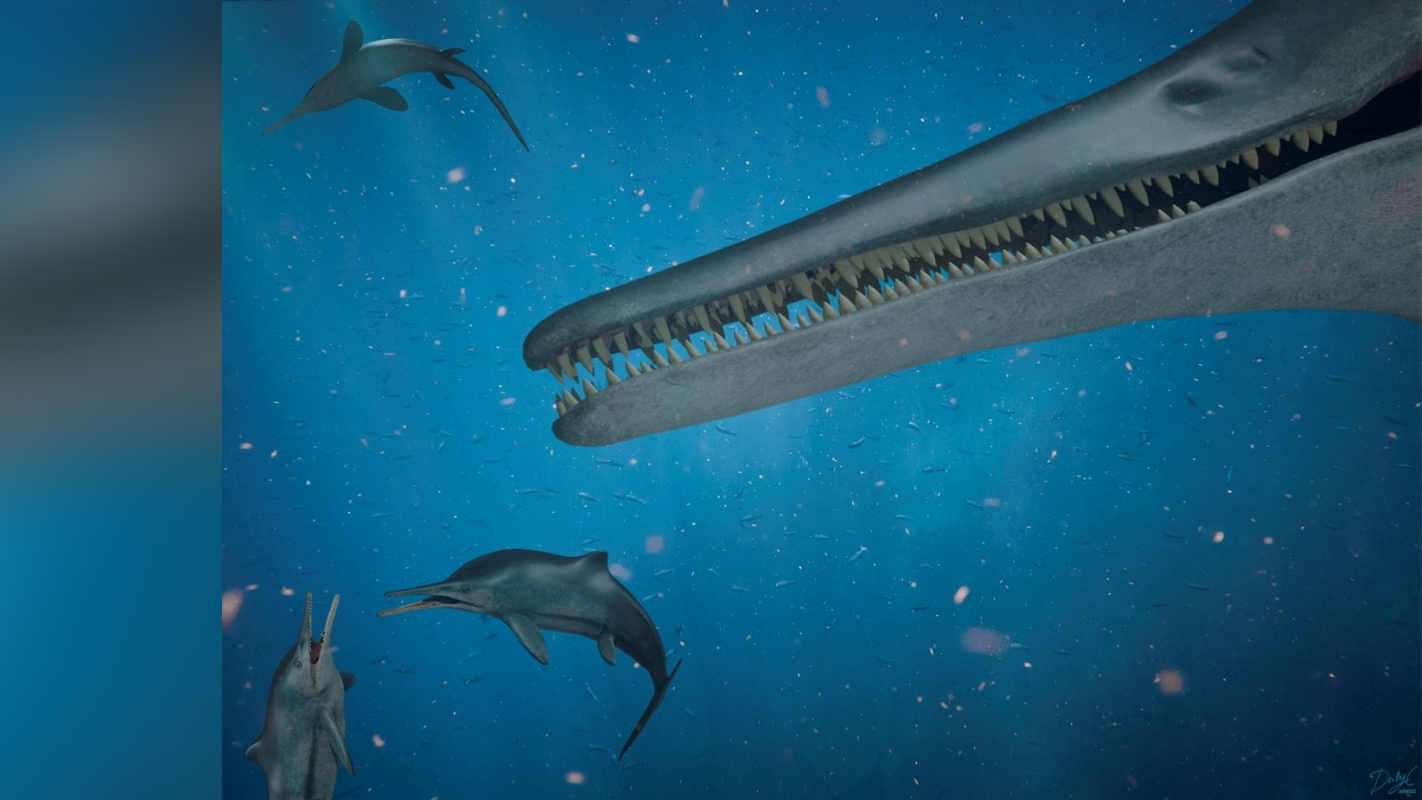

You wouldn't want to meet an ichthyosaur while taking a dip in the early Cretaceous seas. That goes double for Kyhytysuka sachicarum: This newly identified 130 million-year-old marine reptile, now known from fossils in central Colombia, had larger, more knife-like teeth than other ichthyosaur species, a new study finds — and that is saying something, as ichthyosaurs are famous for their long, toothy snouts.

These big teeth would have enabled K. sachicarum to attack large prey, such as fish and even other marine reptiles.

"Whereas other ichthyosaurs had small, equally sized teeth for feeding on small prey, this new species modified its tooth sizes and spacing to build an arsenal of teeth for dispatching large prey," paleontologist Hans Larsson of McGill University's Redpath Museum in Montreal, Canada, said in a statement.

Related: Fossilized 'ocean lizard' found inside corpse of ancient sea monster

One toothy family

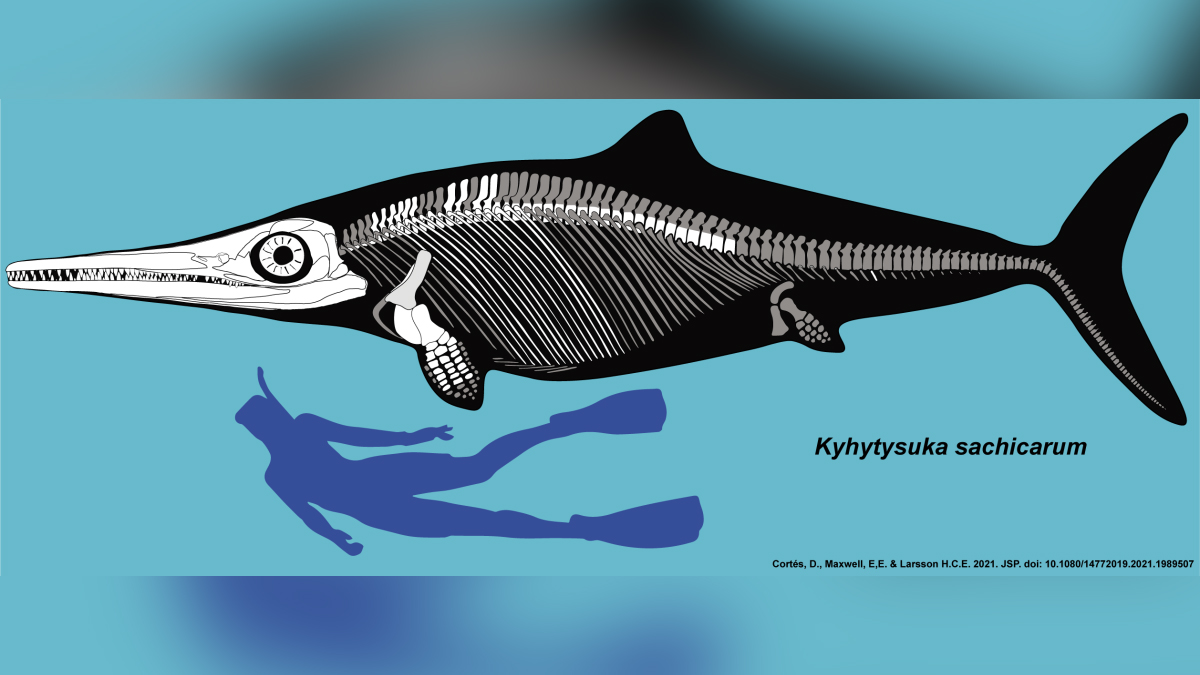

Ichthyosaurs were a large group of marine predators that first evolved during the Triassic period around 250 million years ago from land-dwelling reptiles that returned to the sea. The last species went extinct about 90 million years ago during the late Cretaceous. With long snouts and large eyes, they looked a bit like swordfish. Most species had jaws lined with small, cone-shaped teeth that were good for snagging small prey.

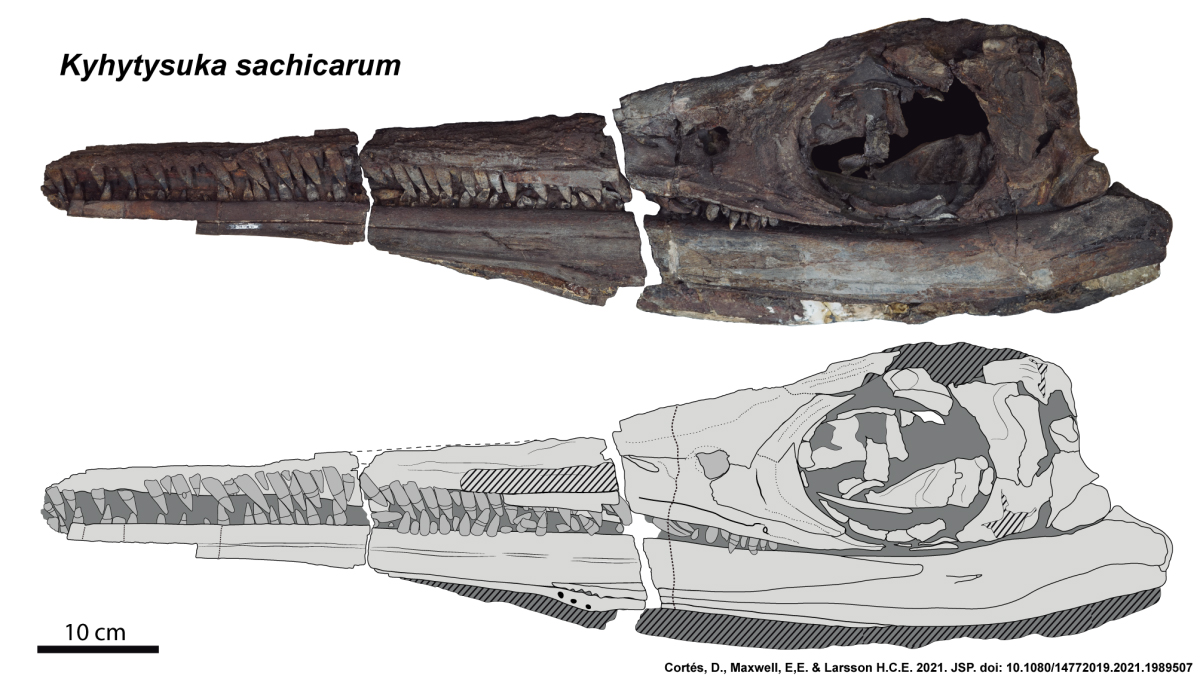

The newly identified species was likely at least twice as long as an adult human, based on the size of the fossils that have been found (most of a skull and a few pieces of spine and ribs). Probable ichthyosaur fossils were first unearthed in Colombia in the 1960s, but researchers couldn’t agree on the species or precisely how ichthyosaurs from the region were related to others from the same time period.

For the new study, Larsson and his colleagues focused on a skull kept in the collections of Colombia's Museo Geológico Nacional José Royo y Gómez, and also considered another partial skull and bones from the spine and ribcage kept at Colombia's Centro de Investigaciones Paleontológicas. Larsson and his colleagues announced the discovery and name of the marine reptile Nov. 22 in the Journal of Systematic Paleontology.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We compared this animal to other Jurassic and Cretaceous ichthyosaurs and were able to define a new type of ichthyosaurs," Erin Maxwell of the State Natural History Museum of Stuttgart, Germany, said in the statement. "This shakes up the evolutionary tree of ichthyosaurs and lets us test new ideas of how they evolved."

Marine predator

The researchers named the new ichthyosaur species Kyhytysuka, meaning “the one that cuts with something sharp” in the language of the Indigenous Muisca culture of Colombia.. There are other species of ichthyosaur with big teeth for catching large prey, the researchers wrote in the study, but those species are from the early Jurassic, at least 44 million years earlier than K. sachicarum.

The new species lived at a time when the supercontinent Pangea was breaking up into two landmasses — one southerly and one northerly — and when Earth was warming and sea levels were rising. At the end of the Jurassic, the seas underwent an extinction upheaval, and deep-feeding ichthyosaur species, marine crocodiles and short-necked plesiosaurs died out. These animals were replaced by sea turtles, long-necked plesiosaurs, marine reptiles called mososaurs that looked like a mix between a shark and a crocodile, and this huge new ichthyosaur, said study co author Dirley Cortés of McGill's Redpath Museum.

"We are discovering many new species in the rocks this new ichthyosaur comes from," Cortés said in the statement. "We are testing the idea that this region and time in Colombia was an ancient biodiversity hotspot and are using the fossils to better understand the evolution of marine ecosystems during this transitional time."

Originally published on Live Science

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.