'Extremely rare' fossilized dinosaur voice box suggests they sounded birdlike

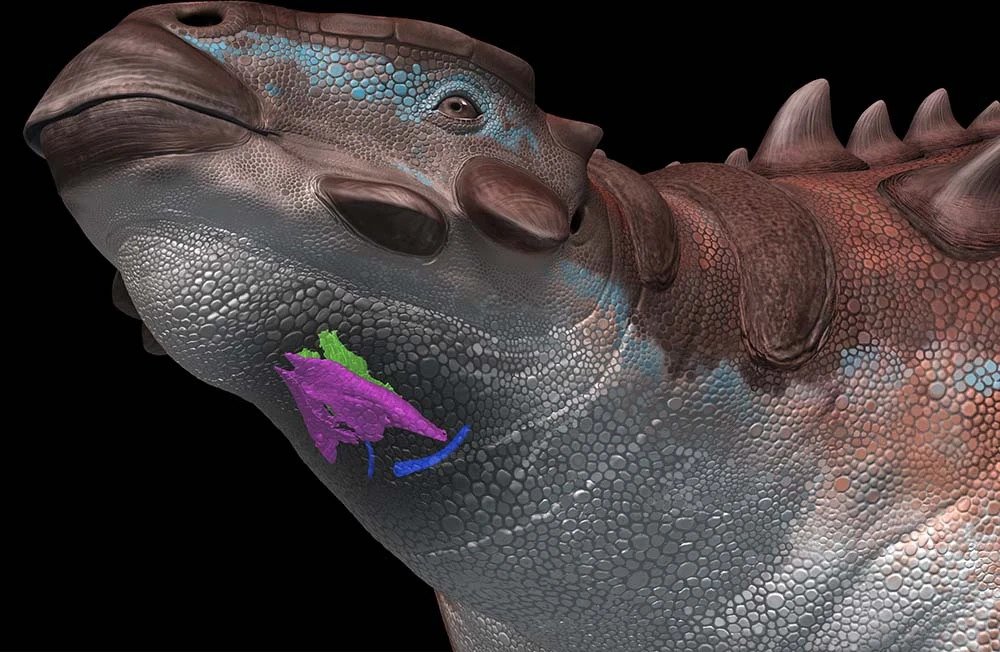

A fossilized ankylosaur voice box reveals that these beasts may have sported a far more sophisticated vocal range than scientists originally thought.

The "extremely rare" discovery of an 80 million-year-old fossilized voice box that belonged to an armored dinosaur reveals that the ancient beast may have sounded more birdlike than experts previously thought, new research suggests.

Pinacosaurus grangeri — a squat, armor-plated and club-tailed ankylosaur unearthed in Mongolia in 2005 — was discovered with the first fossilized voice box (larynx) found in a non-avian dinosaur.

Now, a new analysis, published Feb. 15 in the journal Communications Biology, suggests that the creature's vocalizations may have been far more subtle and melodious than its previously assumed crocodilian grunts, hisses, rumbles and roars.

Related: Scientists find the earliest evidence of a dinosaur eating a mammal

"Our study finds the larynx of Pinacosaurus is kinetic and large, similar to birds that make a variety of sounds," study first author Junki Yoshida, a paleontologist at the Fukushima Museum in Japan, told Live Science. Dinosaurs are archosaurs, a group whose living members include crocodilians and birds. These animals use sound for a variety of purposes, including courtship, parental behavior, defense against predators and territorial calls. "So, these are the candidates for its acoustic behavior," Yoshida said.

At the beginning of the Triassic period roughly 250 million years ago, archosaurs split into two broad groups: a birdlike group that later evolved into dinosaurs, birds and pterosaurs, and a second group that later branched out into crocodiles, alligators and a number of extinct relatives.

Most animals that produce sounds do so through specially adapted organs connected to the lungs by the windpipe. In crocodiles, mammals and amphibians, the larynx — a hollow tube located at the top of the windpipe and crammed with folds of resonating tissues — is adapted to produce sounds. But in birds, the syrinx — a two-piped structure resting near the lungs, at the bottom of the windpipe — creates the foundations for complex melodies.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To assess the range of sounds P. grangeri might have made, the researchers studied two parts of the fossilized larynx that would have worked with muscles to elongate the airway and alter its shape, comparing them with structures in the voice boxes of living birds and reptiles. They found that P. grangeri had a very large cricoid (a ring-shaped piece of cartilage involved in opening and closing the airway) and two long bones that were used to adjust its size — a layout that turned the P. grangeri voice box into a vocal modifier.

This anatomical setup likely meant that the ancient herbivore was capable of making a large array of sounds — including rumbles, grunts, roars and possibly even chirps — while also bellowing them out across vast distances, the researchers said.

That said, it's unlikely that ankylosaurs chirped or warbled like modern-day birds, mainly because they were much bigger and had very different vocal mechanisms.

"It's really hard to even begin to infer what Pinacosaurus sounded like, because this is likely a completely novel vocal organ that produced its own kind of characteristic sound," James Napoli, a vertebrate paleontologist at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences who was not involved with the study, told Live Science. "I think chirpy birdsong is unlikely, despite functional similarities to a syrinx, just because of how large ankylosaurs were. In my head, I imagine low, reptile-y rumbles and grunts and roars with an intricate birdsong-like complexity."

The researchers said their future research will focus on narrowing down the possible range of P. grangeri vocalizations while searching for other specimens that may contain preserved larynges or even a syrinx.

"Dinosaur sounds are one of those persistent unknowns that make this paper all the more exciting," Napoli said. "Without fossilized vocal organs, which are extremely rare, it's really hard to even begin to estimate the limits of dinosaur vocal behavior, much less what they really sounded like."

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.