500-year-old skulls with facial modification unearthed in Gabon

Hundreds of valuable metal objects in the grave hint at the individuals' importance and wealth.

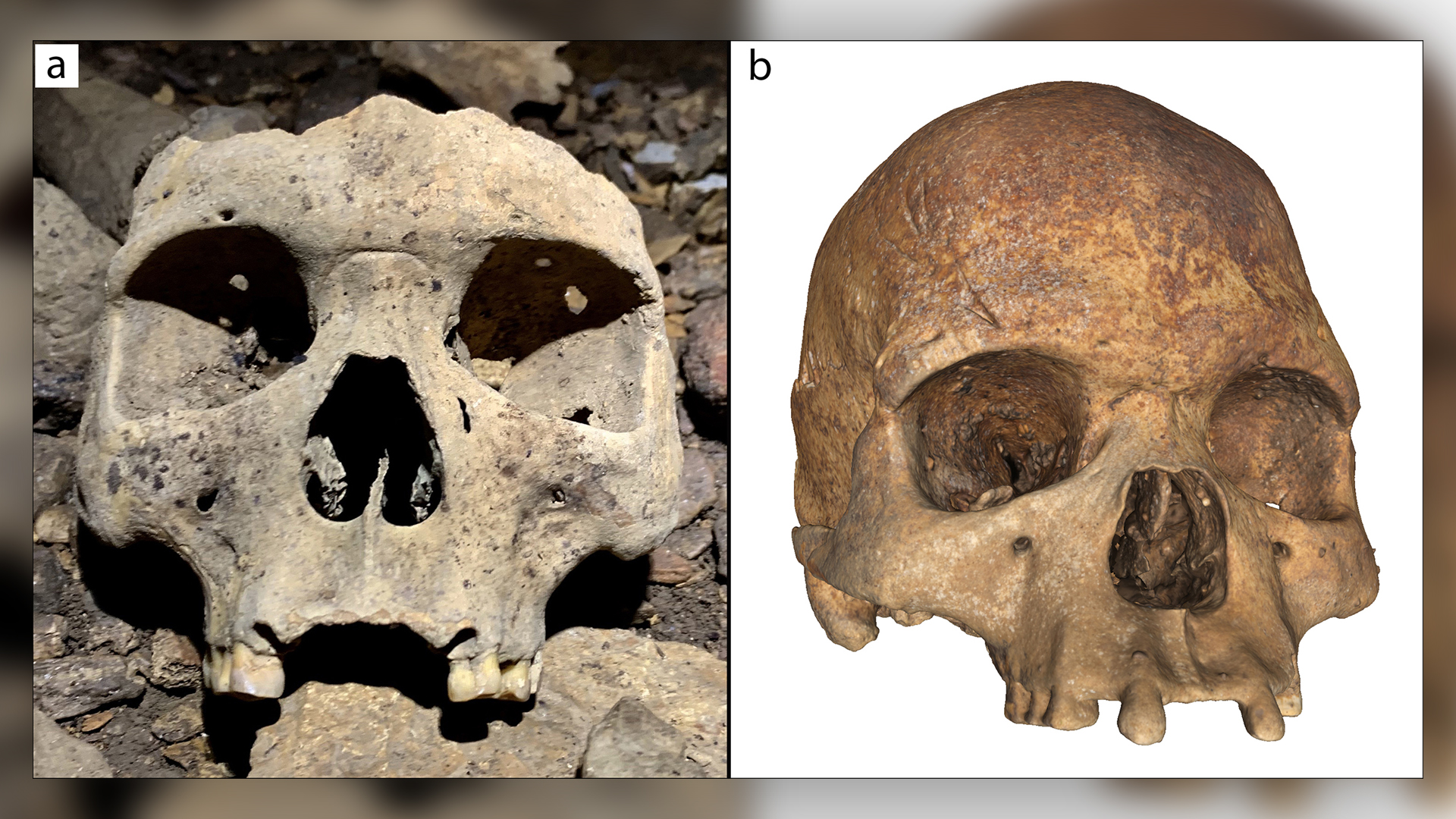

Men and women living in West Central Africa 500 years ago dramatically changed their looks by removing their front teeth, ancient skulls reveal. Archaeologists found the centuries-old altered skulls deep underground in a cave that could be reached only by rope, through a hole in the cavern's roof.

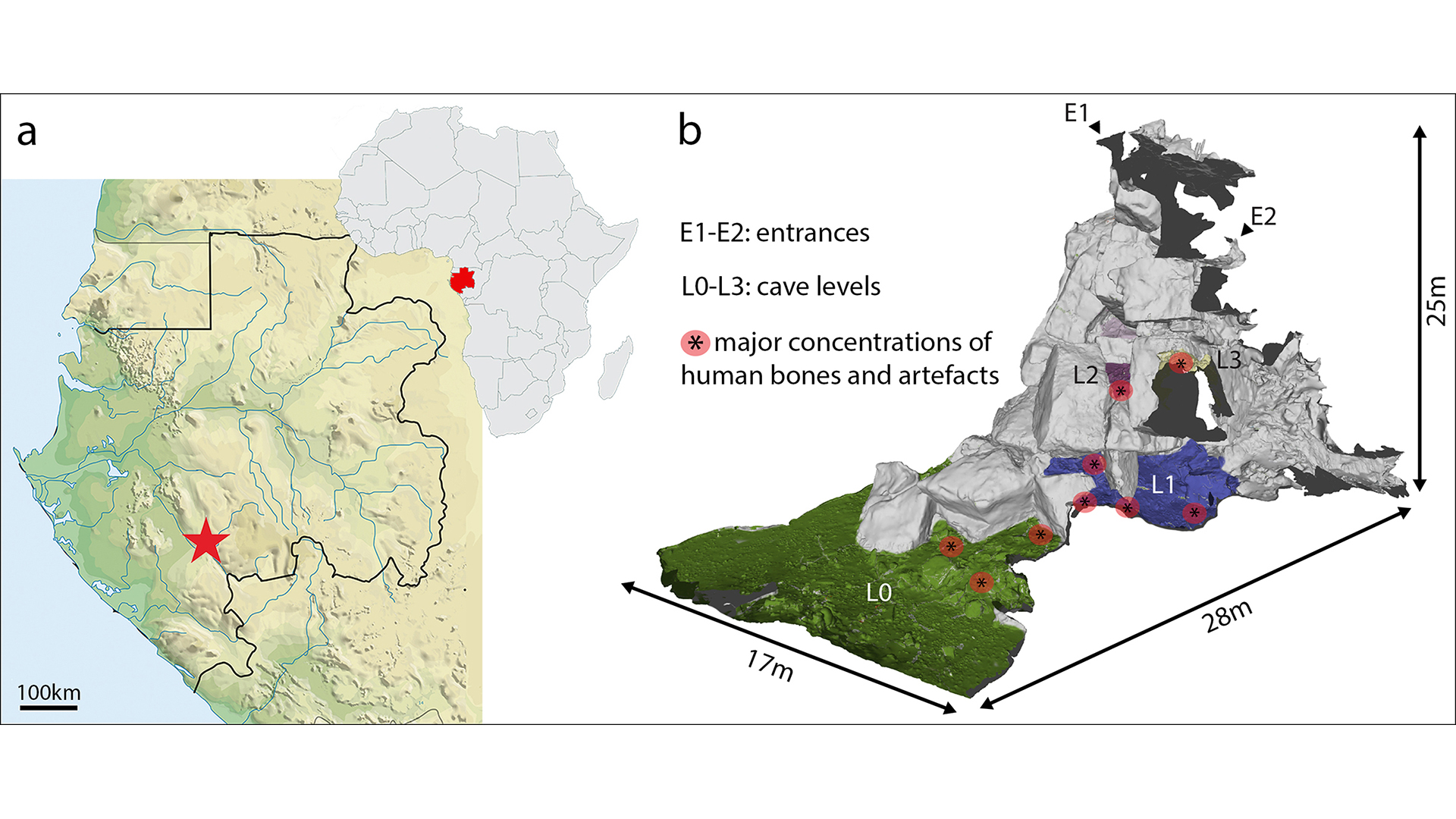

The harrowing vertical drop of 82 feet (25 meters) led to thousands of bones from at least 24 adults (men and women age 15 or older) and four children that were deposited there on at least two occasions, researchers reported in a new study. Hundreds of metal artifacts — jewelry, weapons and hoes, made of local iron and imported copper — lay near the remains, hinting at the wealth and status of the people who were buried there.

Related: In photos: 'Alien' skulls reveal odd, ancient tradition

Richard Oslisly, an archaeologist with The French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) in Paris, discovered the Iroungou cave in Gabon's Ngounié province in 1992. Oslisly first investigated the cave in 2018, and accessing the subterranean space was so difficult that archaeologists have explored its depths on only four expeditions since then, according to the study.

"There are very few sites with archeological human remains for this region," lead study author and CNRS researcher Sébastien Villotte told Live Science in an email. "The fact that children, teenagers, adult males and females were buried here, with so many artifacts — more than 500! — was astonishing."

Scientists photographed and laser-scanned the cave interior and burial sites so that they could reconstruct the cave and its contents in 3D. They collected samples from leg bones for radiocarbon dating — determining an object's age by comparing ratios of radioactive carbon isotopes — but left all of the human remains where they were found.

The cave contained four levels, and all of them held bones dating to the 14th and 15th centuries. Though the bones were jumbled together, scientists noted that all of the skeletons were complete, "suggesting that cadavers, rather than dry bones, were either thrown from above or lowered into the cave," the study authors wrote.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Near the skeletons, there were also plenty of burial objects, such as bracelets and rings; axes and knives; more than 100 marine shells; and dozens of pierced carnivore teeth.

Deliberate removal

Of the human remains, the skulls were of particular interest to the researchers, as all of the intact upper jaws were missing specific teeth: the central and lateral permanent incisors — four teeth in the very front of the mouth. All of the empty tooth sockets showed signs of healing after the extractions — known as alveolar resorption — indicating that the teeth were removed while their owners were still alive and the holes had enough time to heal before the people died.

In 2016, another team of archaeologists found similarly altered skulls, also missing their front teeth, in Brazil's Lapa do Santo cave. But in the case of the Brazilian remains, which date to about 9,000 years ago, the teeth were extracted after death in burial rituals, Live Science previously reported.

Dental modification is a custom that's well documented worldwide, "especially in Africa," Villotte said in the email. "Many various reasons are advocated for tooth removal by the people who practiced it," he added. Sometimes, those reasons include facial modification — extracting teeth in order to change the shape or appearance of the face. The Iroungou skulls clearly weren't modified as part of a burial rite, given that the gums had healed, Villotte said. Because the extractions in the Gabon cave were symmetrical and involved the same teeth in all of the skeletons' jaws, they were likely removed "in the context of some cultural practice" for this population, the scientists said in the study.

The extraction of so many front teeth would have affected pronunciation and changed the shape of the mouth and face in a way that was "highly visible," indicating that all such individuals belonged to a particular group, the researchers reported.

Tooth alterations such as extraction, chipping and filing into points have long been performed across Africa, though the removal of the top four incisors is unusual, according to the study. Most examples of this practice are in populations from West Central Africa, "suggesting a long history and possible continuity of body-modification customs in the area," the researchers wrote.

"As this site is exceptional, and as burial rites are virtually unknown for pre-colonial Gabon, one can consider this discovery as the first piece of the puzzle," Villotte said. "And it seems to be a very difficult one."

The findings were published July 8 in the journal Antiquity.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.