Facial reconstruction shows powerful Bronze Age woman's serene expression and huge earrings

Her hoop earrings hang from earplugs.

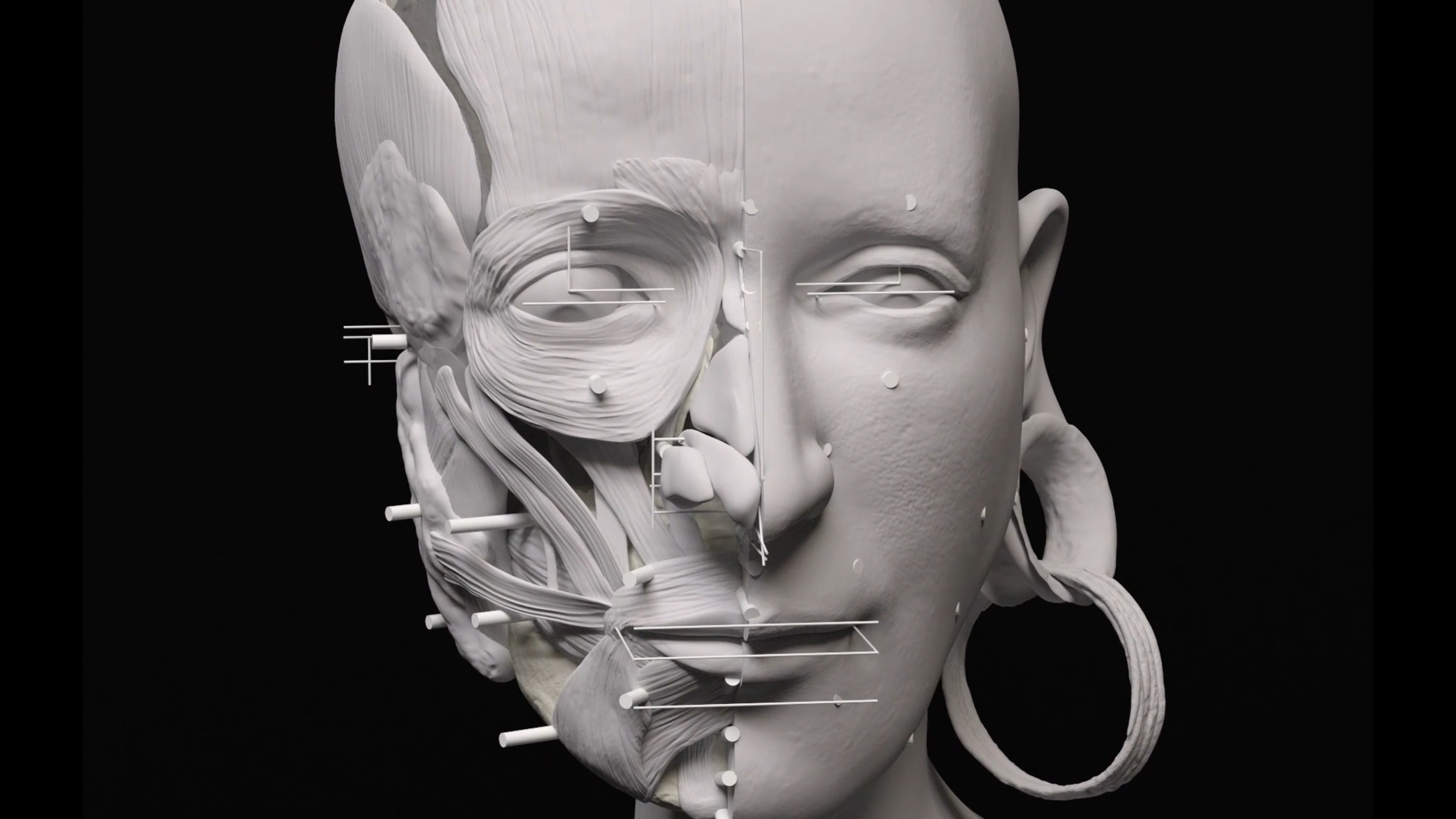

A "powerful, maybe even frightening" woman buried with a silver diadem in Bronze Age Spain now has a virtually reconstructed face that shows her wearing a serene expression and huge hoop earrings dangling from earplugs.

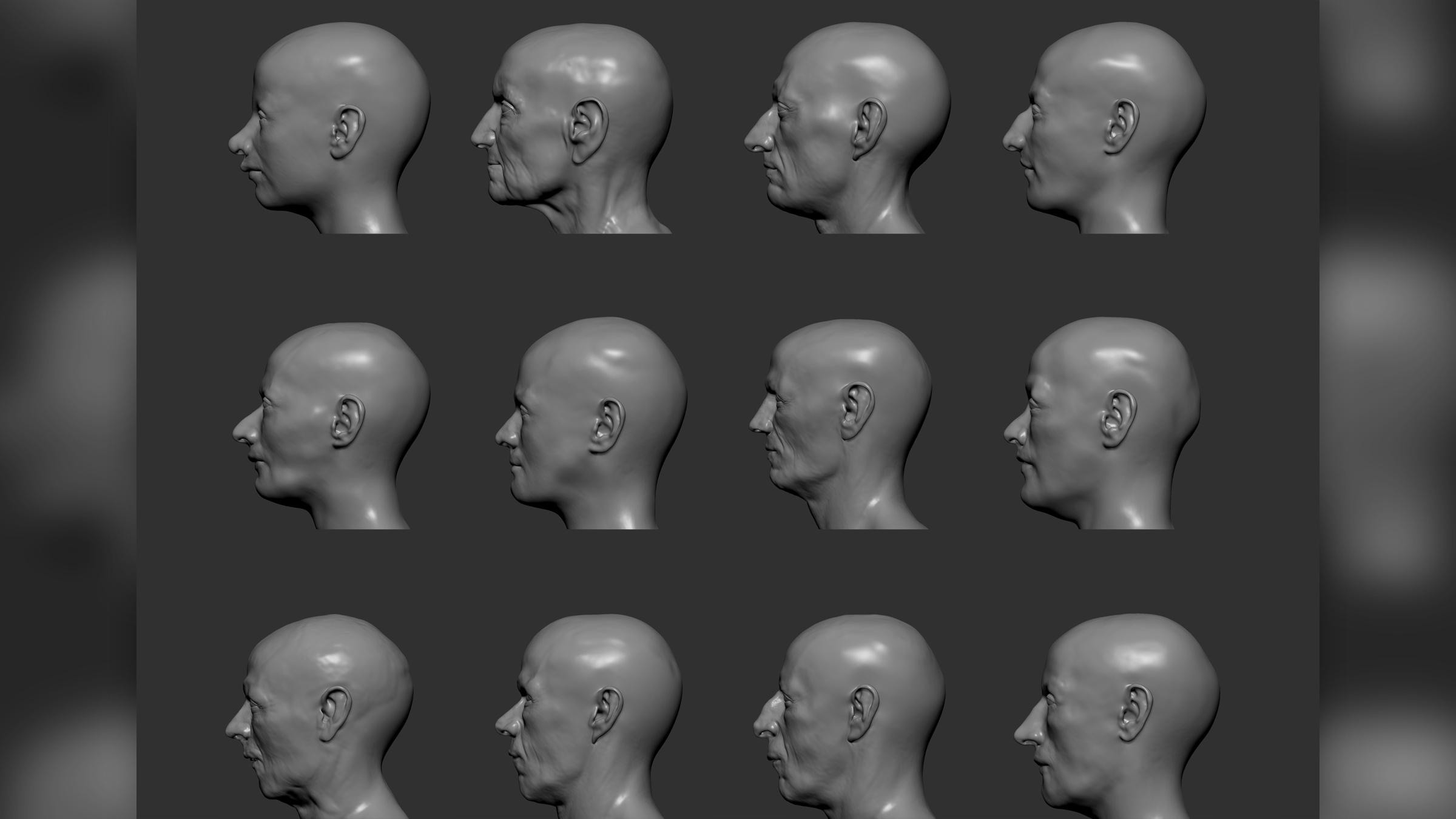

Earlier this year, researchers announced they had discovered the woman's and a man's remains interred together in a large ceramic pot buried in what was likely an ancient palace. The man had died a few years before the woman; after she died at a later date, someone reopened the pot and placed her body next to his. Now, using the partial skull and jewelry from the burial, a scientific Illustrator has digitally recreated the woman's face, as well as the faces of others buried at the site, known as La Almoloya.

"The biggest challenge about this facial reconstruction was that the upper portion of her skull did not survive the ages," Joana Bruno, the freelance scientific illustrator who created the digital reconstructions and a collaborator with the La Almoloya archaeologists at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, told Live Science in an email. "Luckily, the diadem (the silver crown) was found in place, around her head, so that gives us some measure for her head, but it was still a challenge."

Related: 6 times that showed us women from antiquity were totally badass

The diadem-wearing woman's identity has intrigued scientists since archaeologists unearthed her burial in 2014. Her lavish burial goods — including the diadem, beaded necklaces, silver-crafted rings, bracelets, spiral hairpieces and earplugs with spirals, as well as a silver-rimmed drinking pot and silver-handled awl, a tool used to piece textiles — are of superior quality and are more valuable than goods buried with the man, researchers previously told Live Science. Perhaps these riches indicate that the woman had more power than her burial partner, especially given that she outlived him and was still buried with treasured goods, the researchers said at the time.

When Bruno decided to digitally recreate the woman's face, it was in part due to the site's impressive preservation of many of its original inhabitants. "La Almoloya is just a fascinating time capsule," she said. "And, since the DNA can tell us more about their kinship, it is also an opportunity to see if these faces somehow carry similar features that could hint at those shared relationships."

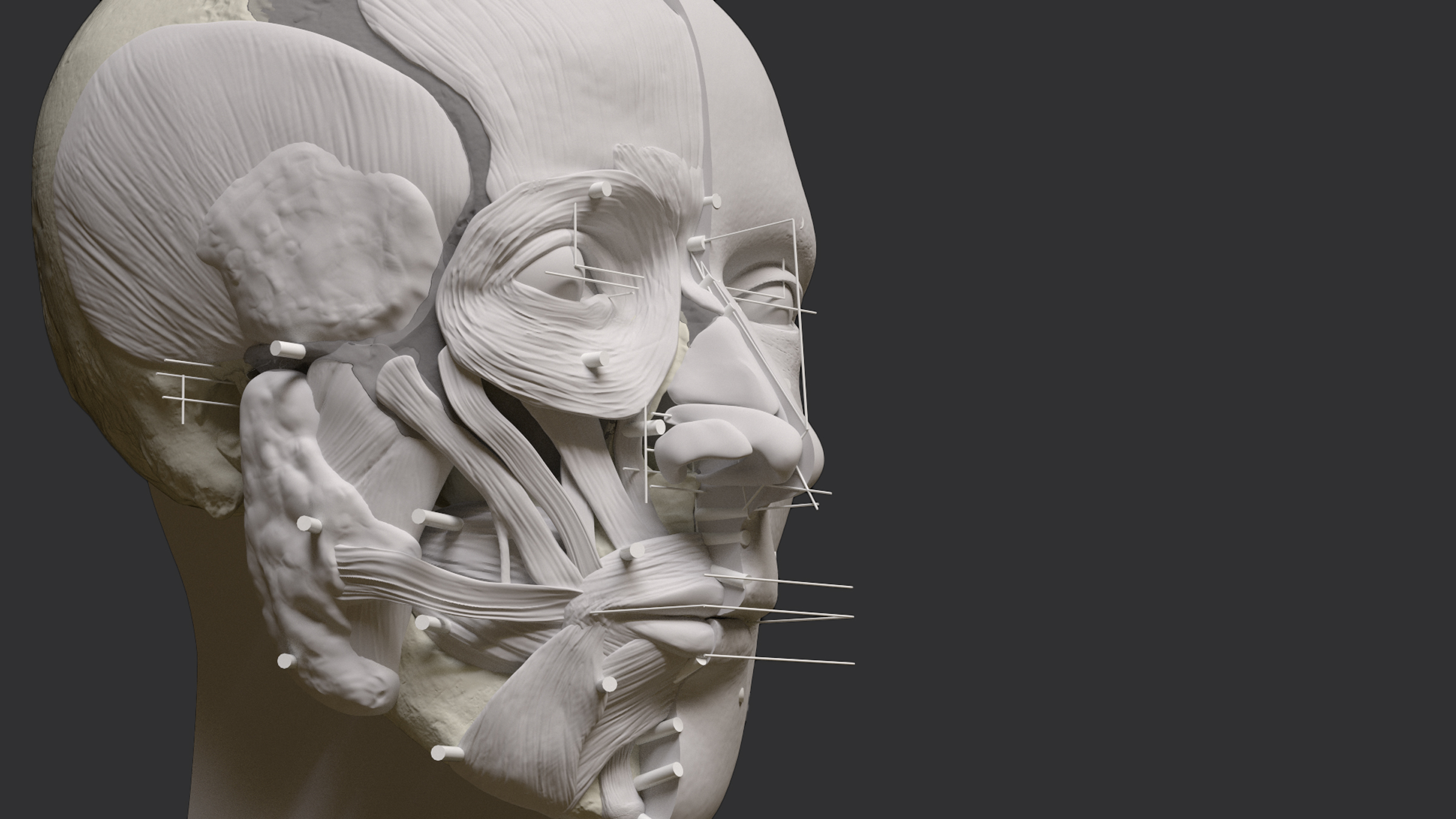

Before any virtual reconstruction, anthropologists clean, stabilize and study the deceased's skeleton to determine the person's sex, age of death, general health and other characteristics. "This information is always taken into account when producing the face reconstruction," Bruno said. In the Bronze Age woman's case, she died between the ages of 25 to 30 years old and had several congenital conditions, including a missing neck vertebra and rib.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

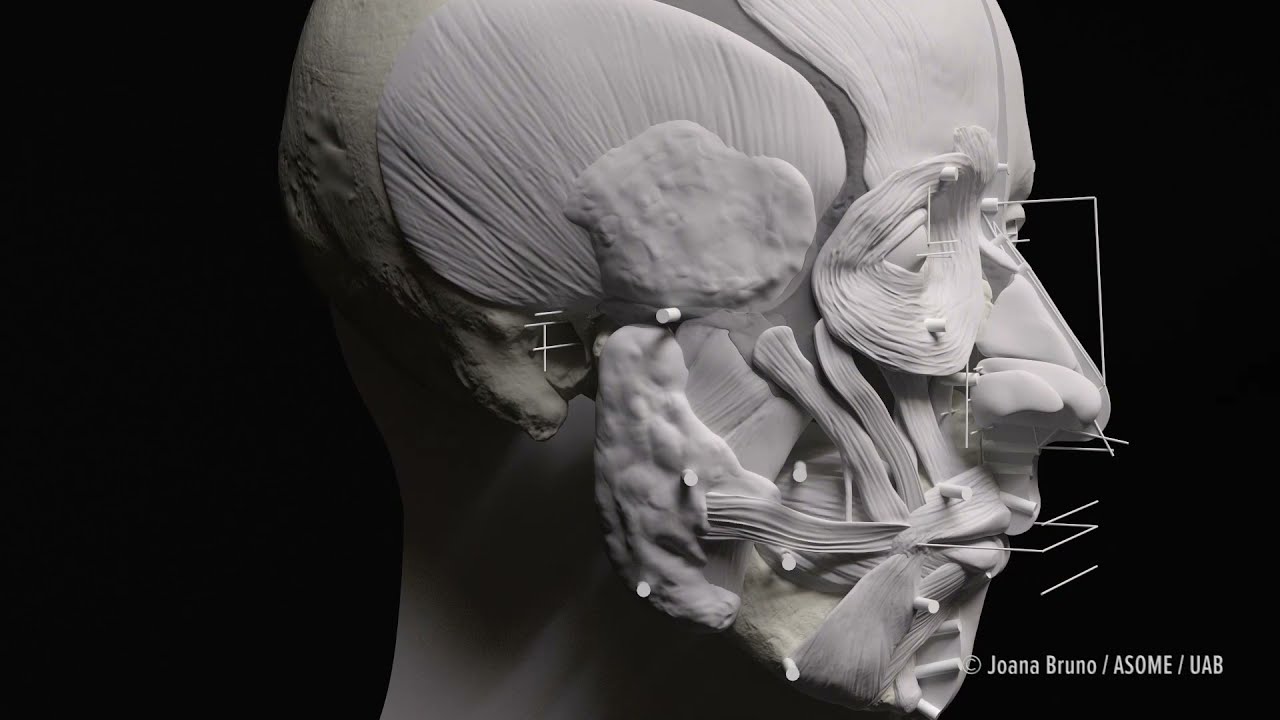

Next, Bruno takes specific measurements of the skull and does a laser scan of the skull and lower jaw. "The laser scan allows me to work with a digital replica of the original and minimize the manipulation of the bones, which are fragile objects," she said. Later, to "flesh out" the face, Bruno relies on published techniques for the speculative process of estimating the position of facial features, such as the eyes, nose and mouth, and determining the thickness of the tissues, she said.

"By doing this, I start 'mapping out' the surface of the skin and, layer by layer, a face starts to emerge," Brunos said. However, she did have to make some guesses. To clarify which bones did not survive, Bruno rendered them as gray and transparent in a video showing the reconstruction process.

"The earlobes were a more straightforward decision," Bruno said. "The earplugs you see in the face reconstruction were found in her tomb, one on each side of her skull. I used laser scans of the earplugs and the diadem in the face reconstruction."

The entire process and Bruno's collaboration with anthropologists highlights "the ability to estimate and 'rebuild' missing skeletal portions with the highest possible accuracy and without damaging the original," Cristina Rihuete Herrada, a professor of archaeology at the Autonomous University of Barcelona and a co-researcher of the 2021 study, told Live Science in an email. "Thanks to the 3D laser scanning of the jewels, Joana has been able to show us that woman's stunning shimmering look."

Bruno is now creating archaeological reconstructions of other El Argar people from La Almoloya "using the faces I reconstructed from their skulls, and including the information generated by the archaeological and genetic research," she said. "It is important to be aware that these bones we now see were real people, with their own domestic dramas, who laughed when someone told a joke, who cared for loved ones and lived in a very different world from our own."

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.