Facts about the dodo

The dodo is an iconic reminder of human-caused extinction.

The dodo (Raphus cucullatus) is an extinct species of bird that once lived on Mauritius, an island off the coast of Madagascar. Dodos, distant relatives of pigeons and other doves, are often referenced as an example of human-caused extinction.

Flightless, slow to reproduce and confined to a single island, dodos were vulnerable to the arrival of humans and rats, as well as the introduction of domesticated animals in the late 1500s. About a century later, all that remained of the dodo were a few paintings and written descriptions, along with a small collection of bones.

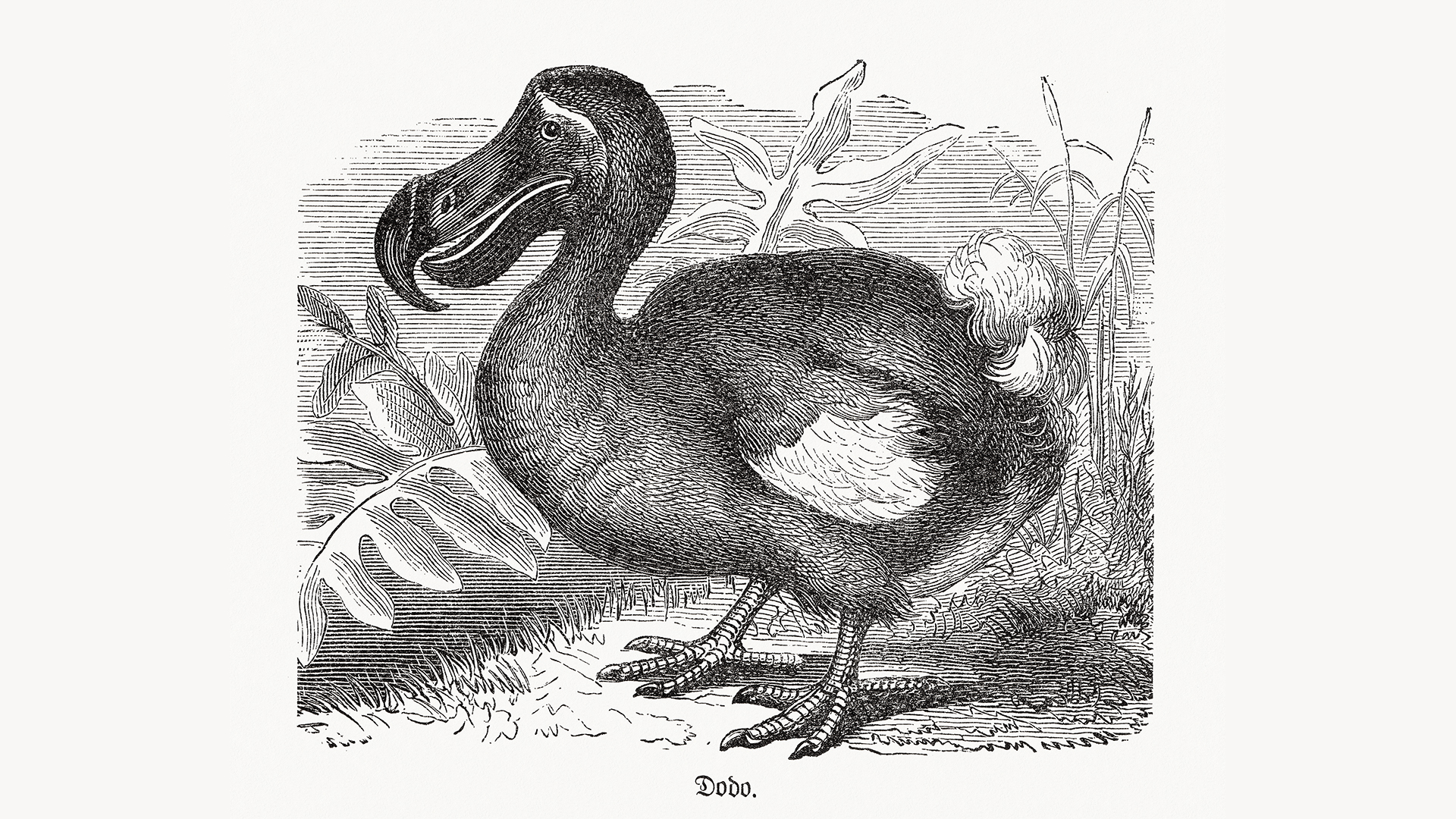

What did dodos look like?

The dodo was a heavyset, gray-brown bird with tiny wings, strong legs and a large beak. It stood up to 27 inches (70 centimeters) tall and weighed 28 to 45 pounds (13 to 20 kilograms), according to a 2004 study in the journal Biologist. Males were slightly larger than females; compared with modern wild turkeys and swans, dodos were shorter but heavier.

Dodos were driven to extinction long before photography could capture their likeness, and no taxidermied specimens of the birds survive. Paleontologist Julian Pender Hume, a research associate at the Natural History Museum (NHM) in London, told Vice that the so-called taxidermied dodo on display at NHM is made of goose and swan feathers that were glued to a plaster model by a man who had never seen a dodo. For evidence of what dodos actually looked like, modern researchers must turn to historical paintings and other artworks, as well as descriptions from early Arab and European visitors to Mauritius, and such records were not always accurate.

One European artist in particular, 17th-century Flemish painter Roelant Savery, is largely responsible for the rotund image of the dodo that proliferated in other artwork and cartoons. Savery's roly-poly dodo led many to perceive the birds as slow, stupid and clumsy, but evidence from dodo bones suggests that the birds were nimble animals that could outpace humans over rocky terrain, Hume said. According to the NHM, the dodo had a large brain and well-developed olfactory glands, indicating that contrary to its popular reputation, it was relatively intelligent and likely had a keen sense of smell.

Where did dodos live?

Dodos lived on the subtropical volcanic island of Mauritius, now an independent state made up of several islands in the Indian Ocean. Mauritius is located about 700 miles (1,100 km) from Madagascar, off the southeast coast of Africa.

Mauritius and its neighboring islands harbored no permanent human population before the Dutch East India Company established a settlement there in the 1600s, according to the Stanford University Department of Anthropology. By then, previous visitors to the island had already introduced so many predators that dodos no longer roamed the beaches and mountains. Later, deforestation removed much of the dodo's woodland habitat, researchers reported in 2009 in the journal Oryx.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Why did the dodo go extinct?

The dodo went extinct through a fatal combination of slow evolution and fast environmental changes, according to National Geographic. Highly specialized to its environment, the flightless and slow-to-reproduce species was vulnerable to the sudden introduction of predators in its once-safe island home.

For millions of years before human explorers set foot on Mauritius, the island had no large, land-based predators. Wildlife on Mauritius evolved to fill various ecological niches, but these isolated species were slow to respond to newly arrived threats from across the ocean, National Geographic reported.For example, dodos were said to have no fear of humans who landed on their island beaches, so the birds were easily caught and killed by hungry Dutch sailors.

And it wasn't just humans who consumed the dodos. Rather, a host of introduced species — including rats, pigs, goats and monkeys — likely caught and ate dodos and their eggs, according to a 2016 study in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Tragically for the dodos, each devoured egg represented a female dodo's only chance for reproduction that year. But for the new arrivals on the island, those nutritious, easy meals were conveniently located within easy reach on the forest floor. If any of the precious eggs survived and hatched, the introduced animals likely outcompeted juvenile and adult dodos for a limited food supply, Hume wrote in 2006 in the journal Historical Biology.

Today, the dodo is officially listed as extinct by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

When did the dodo go extinct?

The dodo's official date of extinction isn't certain. Unlike the thylacine, also called the Tasmanian tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus), a species whose last known individual died in captivity in 1936, dodo populations dwindled far from human observation, roughly around 1662, according to a 2004 study published in the journal Nature. Some researchers, however, point to reports of dodos on Mauritius in the late 1680s, Live Science reported in 2013. In the Nature study, researchers used a statistical method to estimate the extinction of the dodo, pushing the date to as late as 1690.

Could we bring back the dodo?

It's unlikely that we'll see a dodo walking the Earth again anytime soon, according to evolutionary molecular biologist Beth Shapiro, a professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

There are a number of reasons why dodos would be complicated to resurrect, Shapiro told Live Science: They're not good candidates for cloning, because there are very few sources of dodo DNA; bird reproduction is really complicated; and there isn't necessarily a habitat for them to go back to.

"When most people think about de-extinction, they're imagining cloning," Shapiro said. Cloning, the process that created Dolly the sheep in 1996 and Elizabeth Ann the black-footed ferret in 2020, creates an identical genetic copy of an individual by transplanting DNA from a living adult cell into an egg cell from which the nucleus has been removed. Adult cells contain all the DNA needed to develop into a living animal. Egg cells then use that DNA as a blueprint to differentiate themselves into the many kinds of cells — skin, organs, blood and bones — the animal needs.

But no living cells from dodos exist, nor have they existed for hundreds of years. Instead, Shapiro said, you'd have to start with a closely related animal's genome and then tweak it to resemble that of a dodo.

For example, mammoths are also extinct, and scientists haven't found any living mammoth cells. But mammoths were very closely related to modern Asian elephants (Elephas maximus), so researchers such as George Church, a professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School in Boston, are attempting to bring mammoths back from extinction by creating a hybrid mammoth, with some mammoth genes replacing part of the elephant genome in an elephant egg cell. However, there are likely millions of genetic differences between the genome of an Asian elephant and that of a mammoth, according to Shapiro. At best, researchers can only hope to produce an animal that has some mammoth features, rather than resurrecting an extinct species.

As for the dodo, its closest living relative is the Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica), a much smaller and more colorful flying bird found on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in India; the Malay Archipelago; the Solomon Islands; and the Republic of Palau, an island country in the western Pacific Ocean. But whereas mammoths and Asian elephants are pretty closely related (they evolved from a common ancestor 5 million years ago), it's been more than 20 million years since the dodo and the Nicobar pigeon had any common ancestors. Genetic differences between the two bird species are therefore much greater, making it more difficult to create a successful hybrid in the lab, Shapiro said.

In 2022, Shapiro dropped an unexpected dodo bombshell when she acknowledged, in response to an audience question at a Royal Society webinar, that she and her colleagues had successfully sequenced the entire dodo genome. The research has not been peer-reviewed yet, but Shapiro was taken aback by the public and press' excited response to her unintended announcement. The team intends to publish the research in the future.

Reconstructing the dodo genome was no easy feat. First, Shapiro and her team had to find intact dodo DNA, buried in bone marrow that had survived hundreds of years in Mauritius' warm and humid environment (and likely tropical cyclones as well). Then, they had to sort out which recovered DNA belonged to the dodo and which belonged to fungi and bacteria that had invaded the bones as they decomposed.

But that success does not guarantee the resurrection of the dodo. Even with a fully reconstructed dodo genome, researchers face another substantial problem: bird reproductive systems.

Whereas mammals produce egg cells that scientists know how to harvest and manipulate, bird egg cells are tricky. In order to find and replace a bird egg’s DNA, researchers would have to safely and non-destructively locate the microscopic nucleus of the egg, which could be floating anywhere inside of a bulky egg yolk. Finding the tiny packet of genetic material is like "looking for a white marble in a pool of milk," Ben Novak, a lead scientist with the de-extinction conservation group Revive & Restore, told Audubon magazine. So, replacing that genetic material with altered DNA to produce a clone is impossible, Novak said. In his own research on passenger pigeon de-extinction, the strategy is to alter bird gonads instead. By changing the sperm and eggs produced by parent birds, the researchers hope to produce offspring with the desired genes.

Even if scientists managed to revive dodos, the island where they once lived is a very different place nowadays. Deforestation, invasive species and human habitation would make it impossible to reintroduce the dodo without major intervention. "If we haven't first solved the problem that caused their extinction in the first place," Shapiro said, "it might not be worth spending all the energy and effort it would take to bring them back."

Additional resources

To learn more about the risks of extinction, read "Beloved Beasts" (W. W. Norton & Co., 2021) by Michelle Nijhuis, which tells the story of the modern movement to preserve Earth's vulnerable species. If you're curious about de-extinction, check out this Wall Street Journal article about scientists who are working to bring species back from the dead. Last, check out this 2021 paper published in the journal Historical Biology on the changing face of the dodo. The paper explores the effects that books and media like Alice in Wonderland have had on the dodo's reputation and renown long after its disappearance.

Bibliography

Angst, D., A. Chinsamy, L. Steel, & J. P. Hume. (2017). Bone histology sheds new light on the ecology of the dodo (Raphus cucullatus, Aves, Columbiformes)." Scientific Reports, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-08536-3

Cheke, A. (1987). The legacy of the dodo—conservation in Mauritius. Oryx, 21(10), 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605300020457

Dissanayake, R. (2004). What did the dodo look like? Biologist, 51(3), 165–68. https://www.academia.edu/11619405/What_did_the_dodo_look_like

Fritts, R. (2021, April 28). The surprising reason scientists haven't been able to clone a bird yet. Audubon. https://www.audubon.org/news/the-surprising-reason-scientists-havent-been-able-clone-bird-yet

Stanford University Department of Anthropology. (n.d.). Mauritanian Archaeology: History. Retrieved April 12, 2022, from https://mauritianarchaeology.sites.stanford.edu/history

Hume, J. P. (2006). The history of the dodo Raphus cucullatus and the penguin of Mauritius." Historical Biology, 18(2), 69–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/08912960600639400

Hume, J. P., Martill, D. M., & Dewdney, C. (2004). Dutch diaries and the demise of the dodo. Nature, 429(6992), 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02688

International Union for Conservation of Nature. (2016, October 1). Dodo: Raphus cucullatus. IUCN Red List. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22690059/93259513

Kiberd, R. (2015, March 17). The dodo didn't look like you think it does. Vice. https://www.vice.com/en/article/vvbqq9/the-dodo-didnt-look-like-you-think-it-does

Parker, I. (2007, January 14). Digging for dodos. The New Yorker. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2007/01/22/digging-for-dodos

Pavid, K. (n.d.). Recreating the lost world of the dodo. Natural History Museum. Retrieved April 12, 2022, from https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/the-lost-world-of-the-dodo.html

Rijsdijk, K. F., Hume, J. P., De Louw, P. G. B., Meijer, H. J. M., Janoo, A., De Boer, E. J., Steel, et al. (2015). A review of the dodo and its ecosystem: Insights from a vertebrate concentration Lagerstätte in Mauritius. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 35(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2015.1113803

Shapiro, B., Sibthorpe, D., Rambaut, A., Austin, J., Wragg, G. M., Bininda-Emonds, O. R. P., Lee, P. L. M., & Cooper, A. (2002). Flight of the dodo. Science, 295 (5560), 1683–1683. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.295.5560.1683

Originally published on Live Science.

Vicky Stein is a science writer based in California. She has a bachelor's degree in ecology and evolutionary biology from Dartmouth College and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz (2018). Afterwards, she worked as a news assistant for PBS NewsHour, and now works as a freelancer covering anything from asteroids to zebras. Follow her most recent work (and most recent pictures of nudibranchs) on Twitter.