Mysterious 'fast radio burst' detected closer to Earth than ever before

Most FRBs originate hundreds of millions of light-years away. This one came from inside the Milky Way.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Thirty thousand years ago, a dead star on the other side of the Milky Way belched out a powerful mixture of radio and X-ray energy. On April 28, 2020, that belch swept over Earth, triggering alarms at observatories around the world.

The signal was there and gone in half a second, but that's all scientists needed to confirm they had detected something remarkable: the first ever "fast radio burst" (FRB) to emanate from a known star within the Milky Way, according to a study published July 27 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Since their discovery in 2007, FRBs have puzzled scientists. The bursts of powerful radio waves last only a few milliseconds at most, but generate more energy in that time than Earth's sun does in a century. Scientists have yet to pin down what causes these blasts, but they've proposed everything from colliding black holes to the pulse of alien starships as possible explanations. So far, every known FRB has originated from another galaxy, hundreds of millions of light-years away.

Related: 11 fascinating facts about our Milky Way galaxy

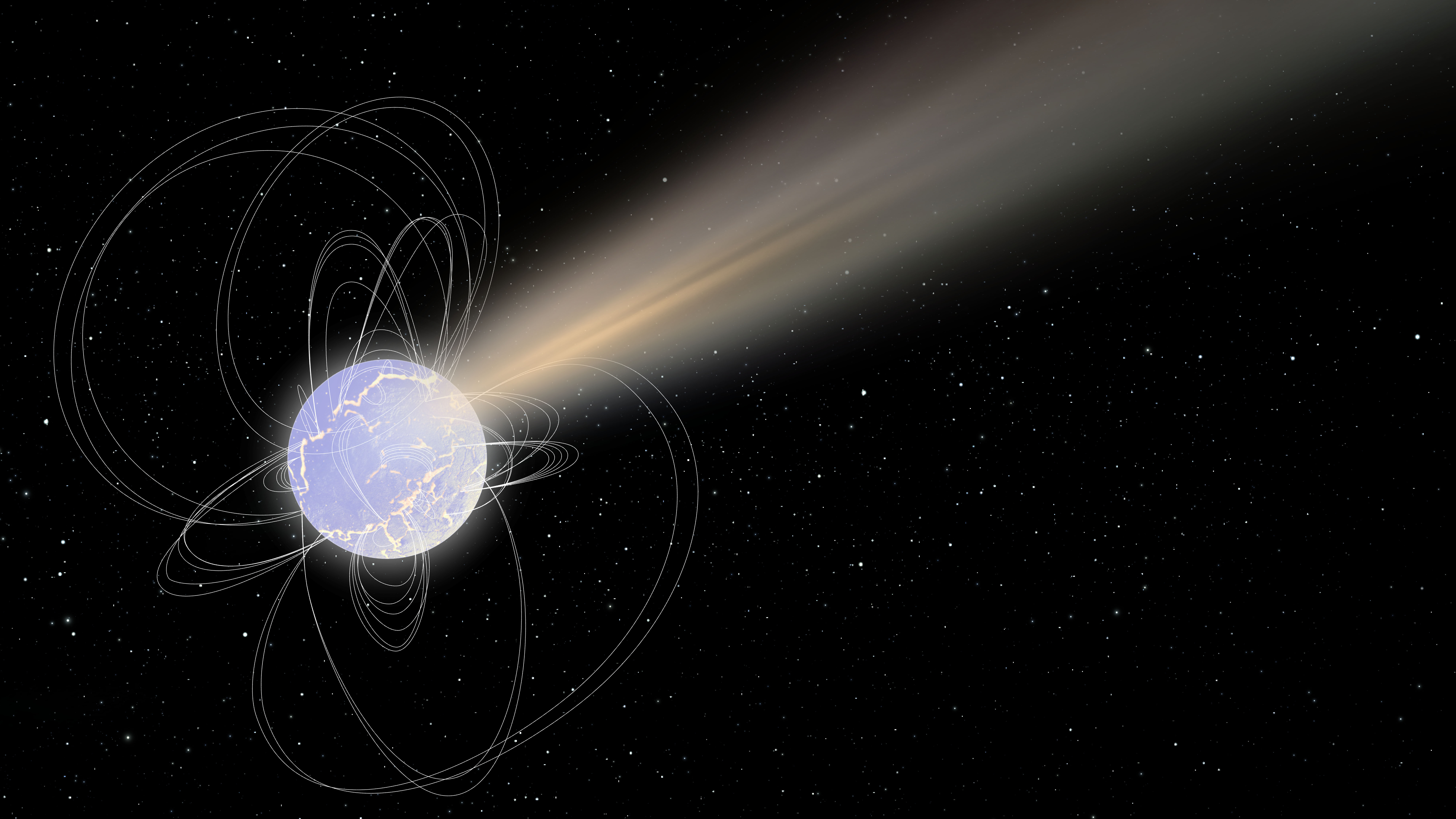

This FRB is different. Telescope observations suggest that the burst came from a known neutron star — the fast-spinning, compact core of a dead star, which packs a sun's-worth of mass into a city-sized ball — about 30,000 light-years from Earth in the constellation Vulpecula. The stellar remnant fits into an even stranger class of star called a magnetar, named for its incredibly powerful magnetic field, which is capable of spitting out intense amounts of energy long after the star itself has died. It now seems that magnetars are almost certainly the source of at least some of the universe's many mysterious FRBs, the study authors wrote.

"We've never seen a burst of radio waves, resembling a fast radio burst, from a magnetar before," lead study author Sandro Mereghetti, of the National Institute for Astrophysics in Milan, Italy, said in a statement. "This is the first ever observational connection between magnetars and fast radio bursts."

The magnetar, named SGR 1935+2154, was discovered in 2014 when scientists saw it emitting powerful bursts of gamma rays and X-rays at random intervals. After quieting down for a while, the dead star woke up with a powerful X-ray blast in late April. Sandro and his colleagues detected this burst with the European Space Agency's (ESA) Integral satellite, designed to capture the most energetic phenomena in the universe. At the same time, a radio telescope in the mountains of British Columbia, Canada, detected a blast of radio waves coming from the same source. Radio telescopes in California and Utah confirmed the FRB the next day.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A simultaneous blast of radio waves and X-rays has never been detected from a magnetar before, the researchers wrote, strongly pointing to these stellar remnants as plausible sources of FRBs.

Crucially, ESA scientist Erik Kuulkers added, this finding was only possible because multiple telescopes on Earth and in orbit were able to catch the burst simultaneously, and in many wavelengths across the electromagnetic spectrum. Further collaboration between institutions is necessary to further "bring the origin of these mysterious phenomena into focus," Kuulkers said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus