Astronomers find the fastest spinning black hole to date

Six decades after its discovery, the first black hole ever detected is still causing astronomers to scratch their heads. It turns out that the cosmic behemoth at the heart of the Cygnus X-1 system is 50% more massive than previously thought, making it the heaviest stellar-mass black hole ever observed directly.

Based on new observations, an international team of researchers estimate the black hole is 21 times the mass of our sun and spinning faster than any other known black hole. The recalculated weight is causing scientists to rethink how bright stars that turn into black holes evolve, and how fast they shed their skins before they die.

Related: Stephen Hawking's most far-out ideas about black holes

The mass of a black hole depends on the properties of its parent star, such as the star's mass and its metallicity (how much of it is made up of elements heavier than helium). Over a star's lifetime, it sheds its outer layers through blasts of stellar winds. Bigger stars rich in heavy elements shed their mass faster than smaller stars with less metallicity, scientists think.

"Stars lose mass to their surrounding environment through stellar winds that blow away from their surface. But to make a black hole this heavy and rotating so quickly, we need to dial down the amount of mass that bright stars lose during their lifetimes," study co-author Ilya Mandel, an astrophysicist from Australia's Monash University said in a statement.

Distance matters

In the new study, researchers estimated the mass of Cygnus X-1 using a tried-and-tested method of measuring the distances of stars from Earth, called parallax. As Earth orbits the sun, astronomers measure the visible movement of stars relative to the background of more distant stars, and with a bit of trigonometry, they can use that movement to calculate the star's distance from Earth.

Related: The 12 strangest objects in the universe

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

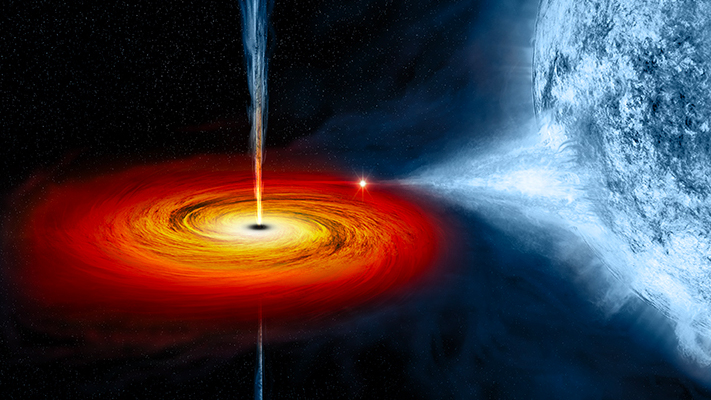

In addition, Cygnus X-1's black hole is slowly devouring its bright blue companion star by sucking in that star's outer layers, forming a bright disk rotating around the black hole. As the matter falls into the black hole, it gets heated to millions of degrees and emits brilliant X-ray radiation. Some of this matter narrowly escapes the black hole and is spit out in powerful jets emitting radio waves detectable on Earth.

It was these signature bright jets that the research team tracked using observations from the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA), a continent-sized network of 10 radio telescopes spread across the United States, stretching from Hawaii to the Virgin Islands. Over a period of six days, they followed the black hole's full orbit around its companion star and determined how much the black hole shifted in space.

They found that Cygnus X-1 is around 7,200 light-years from Earth, surpassing the previous estimate of 6,000 light-years. The updated distance suggests the blue supergiant companion star is brighter and more massive than previously thought, at 40 times more massive than our sun. And given the orbital period of the black hole, they were able to give a new estimate for the black hole's mass — a whopping 21 solar masses.

"Using the updated measurements for the black hole's mass and its distance away from Earth, we were able to confirm that Cygnus X-1 is spinning incredibly quickly — very close to the speed of light and faster than any other black hole found to date," study co-author Lijun Gou, a researcher at the National Astronomical Observatories of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (NAOC), said in the statement.

The discovery is a testament to how improvements in the sensitivity and accuracy of telescopes can unveil mysteries in even some of the most studied parts of our universe.

"As the next generation of telescopes comes online, their improved sensitivity reveals the universe in increasingly more detail," study co-author Xueshan Zhao, a researcher at NAOC, said in a statement. "It's a great time to be an astronomer."

The researchers detailed their findings Feb. 18 in the journal Science.

Originally published on Live Science.