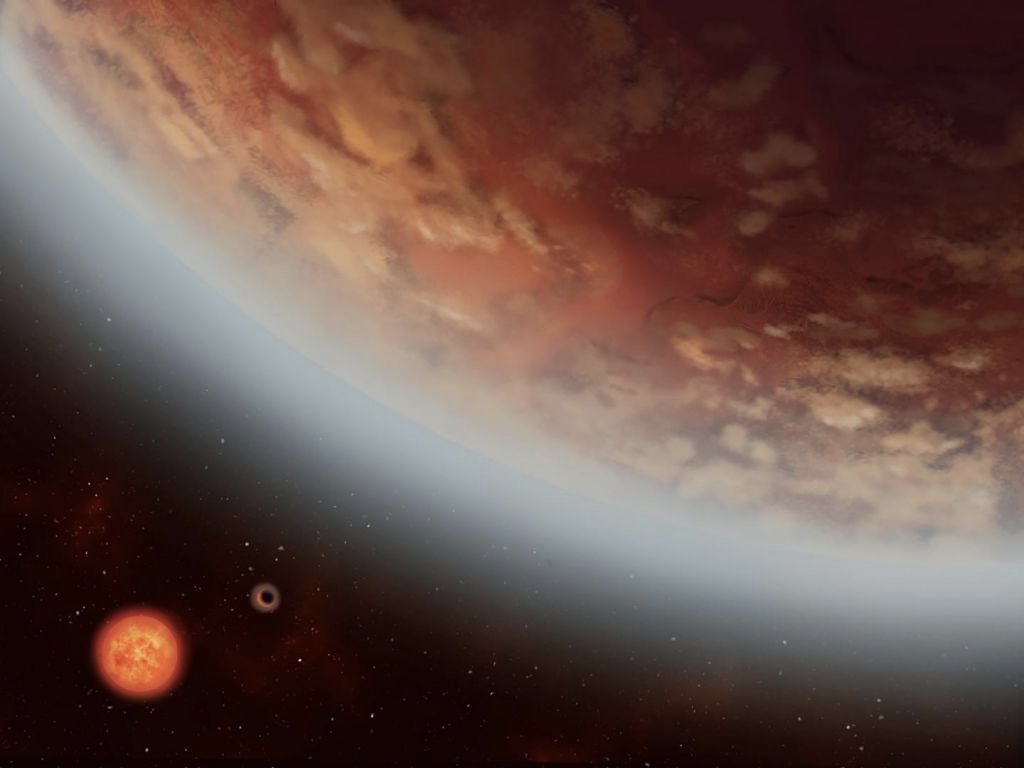

Mysterious Alien Planet Has Water in Its Atmosphere. Could Life Survive There?

The first (known) of its kind.

In a major first, scientists have detected water vapor and possibly even liquid water clouds that rain in the atmosphere of a strange exoplanet that lies in the habitable zone of its host star about 110 light-years from Earth.

A new study focuses on K2-18 b, an exoplanet discovered in 2015, orbits a red dwarf star close enough to receive about the same amount of radiation from its star as Earth does from our sun.

Previously, scientists have discovered gas giants that have water vapor in their atmospheres, but this is the least massive planet ever to have water vapor detected in its atmosphere. This new paper even goes so far as to suggest that the planet hosts clouds that rain liquid water.

"The water vapor detection was quite clear to us relatively early on," lead author Björn Benneke, a professor at the Institute for Research on Exoplanets at the Université de Montréal, told Space.com in an interview. So he and his colleagues developed new analysis techniques to provide evidence that clouds made up of liquid water droplets likely exist on K2-18 b. "That's in some ways the 'holy grail' of studying extrasolar planets … evidence of liquid water," he said.

This study, which has not yet been peer-reviewed, was published Tuesday (Sept. 10) in the preprint journal arXiv.org.

Related: These 10 Exoplanets Could Be Home to Alien Life

A weird world

Because this study has found evidence for liquid water and hydrogen in this exoplanet's atmosphere and it lies within the habitable zone, there is a possibility that this world is habitable. Previous studies have found that other gases that are vital for life as we know it in hydrogen-rich atmospheres of certain planets.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Such studies have suggested that planets with hydrogen-rich atmospheres could host certain forms of life, Benneke said. However, K2-18 b's large atmosphere is extremely thick and creates high-pressure conditions, which "likely prevents life as we know it from existing on the planet's surface," a news release reads.

So, while Benneke does not rule out the possibility that this exoplanet could, in theory, support some sort of life, there is "certainly not some animal crawling around on this planet," Benneke said. This is especially true, given the fact that "there is nothing to crawl on," because the planet doesn't really have a surface, he added.

"Most of that planet, by volume, the vast majority is this gas envelope," he said. As Benneke described, the planet is most likely some sort of core, potentially a rocky one, surrounded by a massive, hydrogen gas envelope that has some water vapor in it.

While these researchers found evidence for liquid water clouds on K2-18 b, because of its lack of surface, rain wouldn't pool on the planet. As rainfall travels through the thick gas surrounding the planet's core, it would become so warm that the water would evaporate back up into the clouds where it would condense and fall again, Benneke said.

Without a real surface, so to speak, landing on the planet would also be nearly impossible to land on, especially because the gas is so thick and has such an incredibly high pressure that any Earth-created spacecraft sent there would be destroyed.

"There are millions of bars of pressure, it would just be crushed and squeezed," Benneke said.

The birth of K2-18 b?

Benneke suggests that, possibly, this planet formed by rock accreting immense amounts of gas, "like a vacuum cleaner," he said. This gas accretion would have more than doubled the planet's radius and increased its volume eightfold. (Today, for comparison, K2-18 b is about nine times as massive as Earth and about twice as large.)

To come to these conclusions, the research team analyzed data from Hubble Space Telescope observations that they made between 2016 and 2017 of the K2-18 b planet passing in front of its star eight times. This technique allows scientists to detect distinct signatures of molecules like water in a planet's atmosphere.

This team plans to expand this research even further by studying K2-18 b with NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, which is set to launch in 2021.

This type of research, Benneke said, is leading toward a final goal of "being able to study real, true Earth-like planets."

"We are not quite there yet," he said, but "this is really exciting."

- How Habitable Zones for Alien Planets and Stars Work (Infographic)

- This Newfound Alien Planet Has a Truly Bizarre Looping Orbit

- Biodiversity on Some Alien Planets May Dwarf That of Earth

Follow Chelsea Gohd on Twitter @chelsea_gohd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Chelsea Gohd joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2018 and returned as a Staff Writer in 2019. After receiving a B.S. in Public Health, she worked as a science communicator at the American Museum of Natural History. Chelsea has written for publications including Scientific American, Discover Magazine Blog, Astronomy Magazine, Live Science, All That is Interesting, AMNH Microbe Mondays blog, The Daily Targum and Roaring Earth. When not writing, reading or following the latest space and science discoveries, Chelsea is writing music, singing, playing guitar and performing with her band Foxanne (@foxannemusic). You can follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd.