1st exoplanet outside the Milky Way possibly discovered

The orb lies 28 million light-years away in the Whirlpool galaxy M51.

For the first time in history, scientists may have just discovered a planet in another galaxy.

The potential exoplanet, called M51-ULS-1b, lies 28 million light-years away in the spiral galaxy Messier 51 (M51), also known as the Whirlpool galaxy. This discovery could be just the tip of the iceberg, revealing many other exoplanets outside the Milky Way.

"We are trying to open up a whole new arena for finding other worlds," Rosanne Di Stefano, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics who led the study which found this object, said in a statement.

Related: The strangest alien planets (gallery)

Searching outside our galaxy

We are trying to open up a whole new arena for finding other worlds...

Rosanne Di Stefano, astrophysicist

For this study, astronomers used NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and the European Space Agency's XMM-Newton space telescope to look at three galaxies beyond the Milky Way. In total, they looked at 55 different systems in M-51, the Whirlpool galaxy, 64 systems in Messier 101 (M-101), or the "Pinwheel galaxy," and 119 systems in Messier 104, or the "Sombrero galaxy."

The team spotted the object in M-51 using transits, which happen when an object transits, or passes, in front of a star. When it does this, it blocks some of the star's light and creates a brief dimming. Previously, scientists have used this method to discover thousands of exoplanets, or planets outside of our solar system (but still in our galaxy).

The first exoplanet discovered was in 1992 and, since then, most exoplanets found have been less than 3,000 light-years from Earth.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But M51-ULS-1b, orbiting 28 million light-years away, would be the first exoplanet ever found in another galaxy.

Related: 7 ways to discover alien planets

To spot the planet, the team led by Di Stefano used Chandra to look for dips in the brightness of X-rays. Because X-rays are produced by small areas on stars, planets passing in front of those stars could actually block out those X-ray emissions entirely. So instead of a subtle dimming of optical light, researchers could see a more obvious transit, which could make it easier to see objects farther away, according to the statement.

"We are trying to open up a whole new arena for finding other worlds by searching for planet candidates at X-ray wavelengths, a strategy that makes it possible to discover them in other galaxies," Di Stefano said.

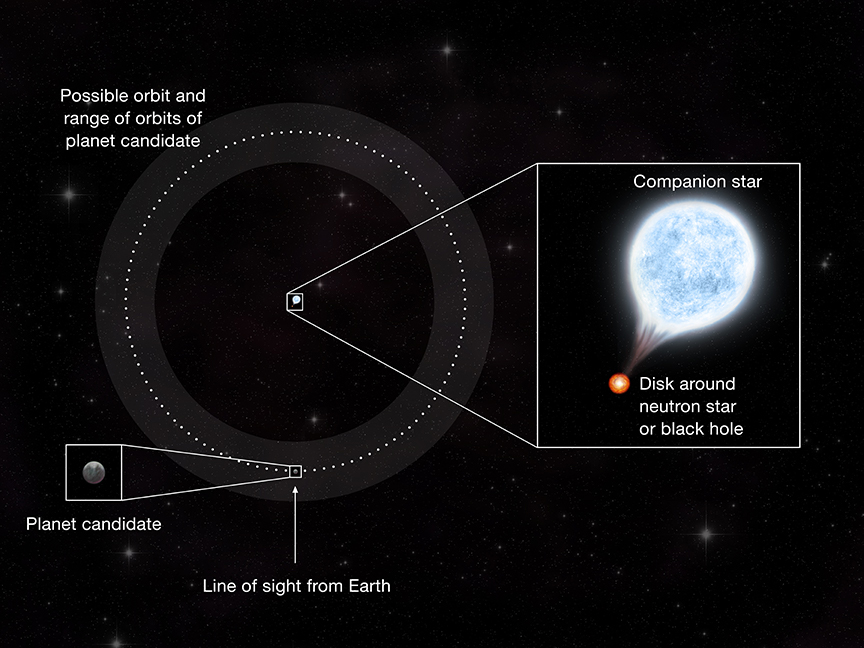

They found the possible exoplanet in the Whirlpool galaxy in a binary system orbiting two large objects: either a neutron star or a black hole which orbits a massive companion star.

The transit they witnessed lasted a total of about three hours and the X-ray emissions dipped all the way to zero. This helped them to figure out that the object is likely approximately the size of Saturn and it orbits the neutron star (or a black hole) at a distance twice that of Saturn's distance from our sun.

Confirming a discovery

This work could be the first to confirm a planet in another galaxy and potentially open up a whole new era of planet detection and study. But right now, these observations do not confirm that the object seen using Chandra in this study is a planet. More data needs to be collected in order to confirm this assertion, researchers said.

However, the object won't transit in front of its star again for 70 years, so it will be a long time before scientists are able to make this observation again.

"Unfortunately to confirm that we're seeing a planet we would likely have to wait decades to see another transit," co-author Nia Imara, a researcher at the University of California at Santa Cruz, added in the same statement. "And because of the uncertainties about how long it takes to orbit, we wouldn't know exactly when to look."

It is possible, but highly unlikely, the researchers acknowledge in the statement, that the dimming could be caused by something like a cloud passing in front of the star. Still, the team has shared that they expect other scientists to look at the data they've collected and what they've found. This could help to verify what they have detected and move this research along, despite the decades left until the next transit.

"We know we are making an exciting and bold claim so we expect that other astronomers will look at it very carefully," co-author Julia Berndtsson, a researcher at Princeton University in New Jersey, added in the same statement. "We think we have a strong argument, and this process is how science works."

This work was described in a study published Oct. 25 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Email Chelsea Gohd at cgohd@space.com or follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Chelsea Gohd joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2018 and returned as a Staff Writer in 2019. After receiving a B.S. in Public Health, she worked as a science communicator at the American Museum of Natural History. Chelsea has written for publications including Scientific American, Discover Magazine Blog, Astronomy Magazine, Live Science, All That is Interesting, AMNH Microbe Mondays blog, The Daily Targum and Roaring Earth. When not writing, reading or following the latest space and science discoveries, Chelsea is writing music, singing, playing guitar and performing with her band Foxanne (@foxannemusic). You can follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd.