NASA captures stunning, first of a kind images of Venus' surface

The images could hold clues into Venus' mysterious past

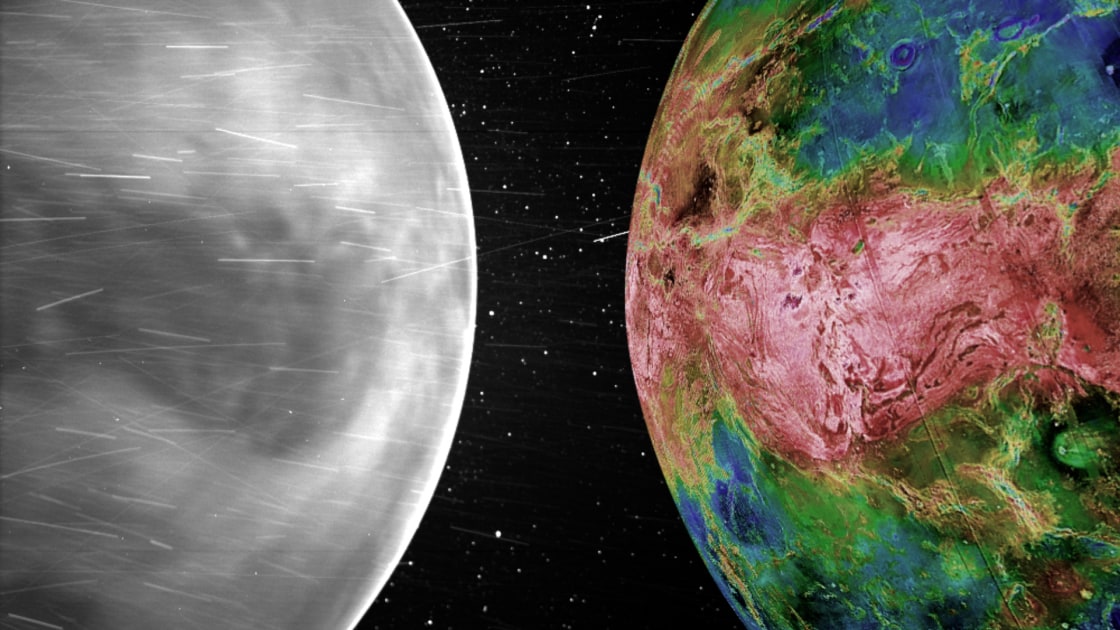

Stunning images snapped by NASA's Parker Solar Probe have given the very first visible light glimpse of Venus' red-hot surface, revealing continents, plains and plateaus on the inhospitable volcanic world.

Peering beneath the thick and toxic Venusian clouds with the Wide-field Imager for Parker Solar Probe (WISPR) instrument, NASA scientists spotted a bevy of geological features lit up in the faint glow of Venus' nightside surface, alongside a luminescent halo of oxygen in the planet's atmosphere.

Related: 6 reasons astrobiologists are holding out hope for life on Mars

The groundbreaking images, taken during the Parker Solar Probe's fourth flyby of Venus on the way to the sun, will give scientists valuable insights into the scorching planet's geology and minerals, and they could reveal more about how Venus became so inhospitable while life on Earth flourished. NASA scientists published their analysis of the images Feb. 9 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

"Venus is the third brightest thing in the sky, but until recently we have not had much information on what the surface looked like because our view of it is blocked by a thick atmosphere," study lead author Brian Wood, a physicist at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C., said in a statement. "Now, we finally are seeing the surface in visible wavelengths for the first time from space."

Venus' surface has been imaged before, but this is the first time it's been snapped in light visible to the human eye. This is because the planet is shrouded by a thick toxic cloak of sulfuric acid and carbon dioxide, blocking most light from escaping.

The Parker Probe's WISPR instrument was never designed with imaging Venus in mind — it was built to study the sun's atmosphere and solar wind — but the instrument's sensitivity enabled it to capture the faint glow of red light emitted by the planet. During the day, this red light is drowned out by sunlight reflecting off Venus' clouds, but the nighttime flyby enabled the probe to pick up the planet's gentle glow, and the stunning geographic features on its surface.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As WISPR detected wavelengths between the visible and the infrared spectrums, it also enabled scientists to estimate Venus' surface temperature. And no surprise, it's hot. At 863.33 degrees Fahrenheit (462 degrees Celsius), the lava-drenched planet is the hottest planet in our solar system, even at night.

"The surface of Venus, even on the nightside, is about 860 degrees," Wood said. "It's so hot that the rocky surface of Venus is visibly glowing, like a piece of iron pulled from a forge."

The new images will be analyzed alongside past images of Venus — such as those captured by the 1975 Soviet Venera 9 landing missions; NASA's 1990 Magellan mission; and the Japanese space agency’s Akatsuki mission — to help scientists understand how Venus grew to be so inhospitable. Scientists don't know if Venus was always as barren as it is today, and past research has suggested that the planet may have hosted water and even life before it was smothered by a hellish fog of greenhouse gases, Live Science previously reported.

The Parker probe is using Venus for "gravity assist" maneuvers to fine-tune the probe's course to the sun, and it will slingshot from the planet into a solar orbit in November 2024. But this isn't the last of NASA's plans for Venus. NASA’s Veritas and Da Vinci missions will expand the U.S. space agency's knowledge of the planet's surface by sending an orbiter and an atmospheric probe to the planet. These missions are expected to launch sometime between 2028 and 2030. The European Space Agency will also send its own orbiter, EnVision, to scan the planet's surface. Together, the three could unlock the secrets of Venus' past, and maybe even offer a chilling warning for one of Earth's possible futures.

Originally published on Live Science.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.