Baby elephants frolicked in an ancient 'nursery,' fossil footprints show

Like modern elephants, their extinct relatives likely lived in matriarchal groups.

More than a dozen young elephants — newborns, toddlers and teens — gamboled through mud in an ice age elephant "nursery" in southwestern Spain more than 100,000 years ago, according to new analysis of tracks that the youngsters left behind.

Scientists examined 34 sets of tracks belonging to straight-tusked elephants (Palaeoloxodon antiquus) — extinct relatives of modern elephants — at a site known as the Matalascañas Trampled Surface in Huelva, on the Iberian Peninsula. As the name implies, this was a high-traffic area for a short period of time during the latter part of the Pleistocene epoch (2.6 million to about 11,700 years ago), when diverse animals, including Neanderthals, crisscrossed the surface.

The presence of Neanderthal footprints — adult and juvenile — hint that they may have visited the nursery to hunt vulnerable elephants, preying on calves, targeting females in labor "or opportunistically scavenging stillbirths and females dead from birth," according to a new study.

Related: Photos: Finding elephant tracks in the desert

Most of the elephant tracks at the site belonged to youngsters, which were accompanied by several young adult females. Only two tracks were thought to have been made by adult males, suggesting that the area was a reproductive habitat primarily occupied by females and their young. The dense concentration of elephant tracks provides "evidence of a snapshot of social behavior, especially parental care," the researchers reported.

Straight-tusked elephants "were one of the most impressive species of elephant that ever lived," said lead study author Carlos Neto de Carvalho, a geologist and scientific coordinator of Naturtejo Global Geopark, a protected territory in inland Portugal containing geologic features that are recognized by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

These elephants stood over 13 feet (4 meters) tall at the shoulder and weighed up to 17 tons (15 metric tons). Biologists who study modern elephants can estimate an animal's size, age and body mass based on the size, shape and depth of tracks, and Neto de Carvalho and his colleagues applied the same methods to the ice age tracks, he told Live Science in an email.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Most of the young elephants that produced the site's smallest tracks were "quite tiny," he said. Their estimated shoulder heights were just 24 inches (60 centimeters), and they would have weighed about 155 pounds (70 kilograms).

The Matalascañas Trampled Surface is usually blanketed by several feet of beach sand, which is "wonderful for the tourists visiting the coast of Andaluzia, but terrible for very curious paleontologists," Neto de Carvalho said. However, spring storm surges in 2020 washed away sand and uncovered a vast area covered with thousands of tracks and trackways.

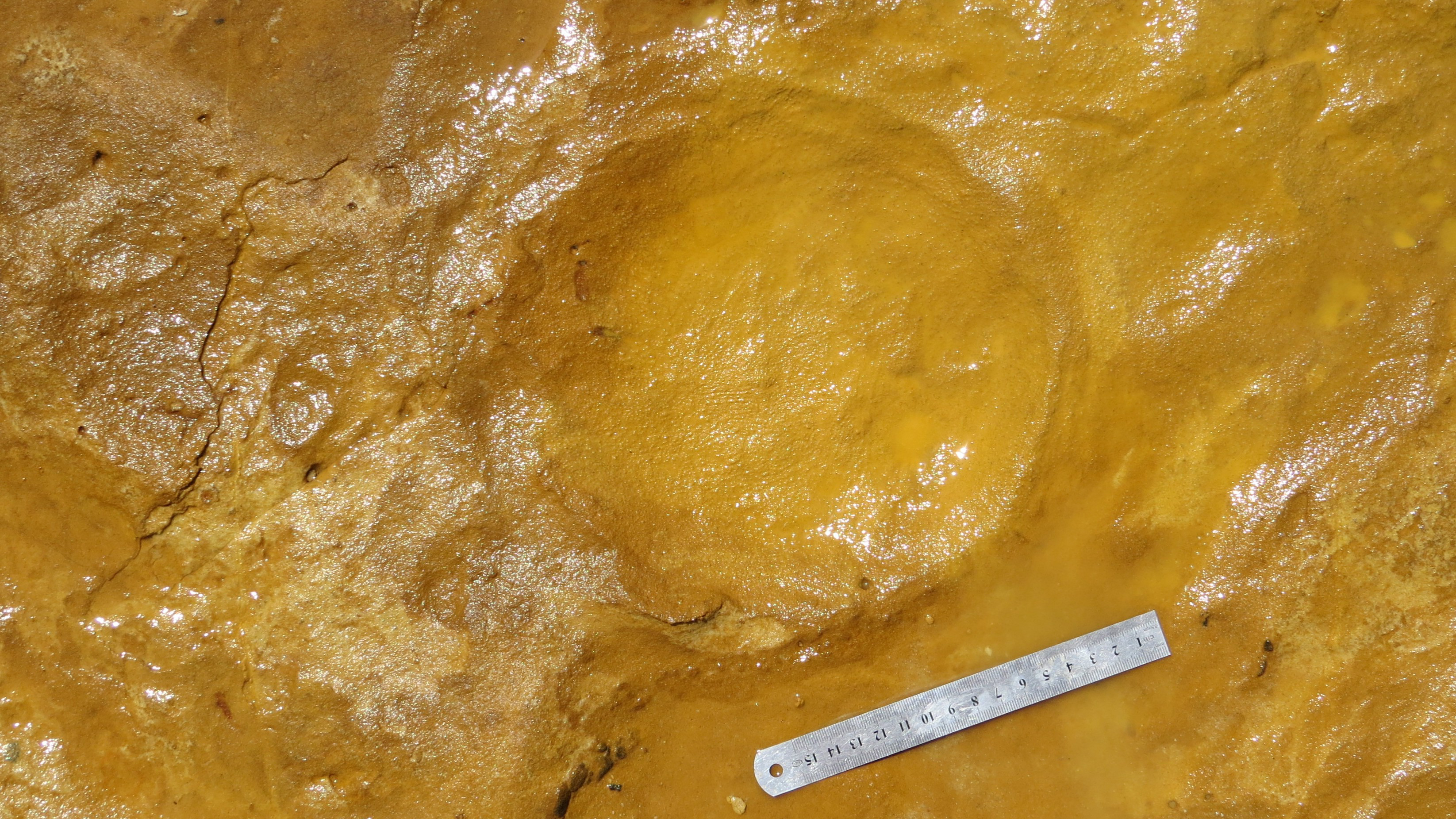

Of those, hundreds were oval footprints associated with elephants and their close relatives, measuring from 3.8 to 21.5 inches (9.6 to 54.5 cm) in diameter. For the study, the scientists described tracks that they could definitively link to individual straight-tusked elephants, Neto de Carvalho said. There were 15 babies under 2 years old; eight youngsters between 2 and 7 years old; six adolescents ages 8 to 15 years; and five adults aged 15 years or older.

In modern elephants, social groups are sexually segregated. They typically revolve around a matriarchal family made up of related females caring for their young, with males leaving a group when they become sexually mature (around age 14 or 15) and then returning to female-led groups to mate, the scientists wrote in the study. Matalascañas, which had seasonal ponds and nutritious vegetation, would have been a perfect spot for an elephant nursery because young elephants need to drink frequently and can't travel as far as adults can, so female-led groups usually stick close to water.

Other coastal dune sites in Portugal that preserve straight-tusked elephant tracks also show that herds were small and made up of females and offspring. All of these trackways were found at sites "with ages over 100,000 years to at least 70,000 years ago, so matriarchal herds of straight-tusked elephants have been visiting the coastal areas for thousands of years," Neto de Carvalho said.

"In the case of Matalascañas, there is good ecological evidence for the behavioral purpose of such visits," he added. "They were giving birth close to small freshwater lakes and ponds in an open landscape, where predators of the newborn could be controlled from afar."

However, Neanderthal footprints — and stone tools that were also found at the site— suggest that elephant families may not have been able to evade hungry human predators. Preserved evidence from other locations hints that elephants and their relatives, "especially young individuals," were a major part of the Neanderthal diet, according to the study. A coastal nursery such as Matalascañas, where newborns, calves and vulnerable females were plentiful, could have been a seasonal elephant buffet for Neanderthals, the researchers reported.

The findings were published Sept. 16 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.