First remains from doomed 19th-century Arctic expedition identified

On July 9, 1845, John Gregory wrote a letter to his wife. That's the last time his family would hear from him.

On July 9, 1845, John Gregory, an engineer on an ocean expedition to the Arctic, wrote a letter to his wife, Hannah, from a stop in Greenland.

That was the last time his family would hear from Gregory, who, along with 128 others, perished after their ships became trapped in the Arctic ice. Now, using DNA from his descendants, researchers have identified Gregory's remains, the first from the ill-fated expedition to be linked to a name, according to a new study.

In May 1845, 129 officers and crew, under the command of Sir John Franklin, set sail from England aboard two ships — the HMS Erebus and the HMS Terror — to explore the Northwest Passage that connects the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Canadian Arctic.

The polar expedition was destined to become the deadliest in history.

Related: In photos: Arctic shipwreck solves 170-year-old mystery

Disaster struck when the ships became trapped in the Canadian Arctic off King William Island in September of 1846; some of the crew died while stuck on the ship. But 105 crew members survived on the ship's supplies and eventually decided to abandon ship, according to a statement from the University of Waterloo.

The last known communication was a short note on April 25, 1848 that was later found in a stone cairn on the island near the ships, that indicated the explorers' intent to abandon their ships and move south to a trading post on the mainland, Live Science previously reported. They all perished without making it very far.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Since the disaster, archaeologists have discovered the remains of dozens of the explorers scattered in the area, most of them on King William Island, along their planned escape route. Although historians have known the names of those who were aboard the ships, none of the skeletons had been identified. To date, scientists have been able to extract DNA from 27 of the expedition members.

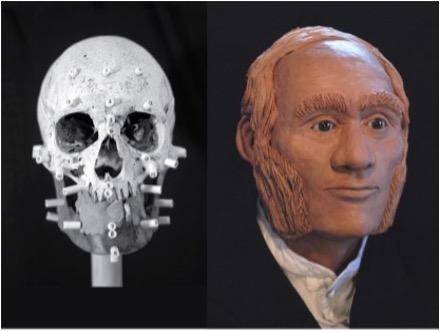

In the new study, the researchers identified, for the first time, the DNA taken from tooth and bone samples of one of three remains found on Erebus Bay, on the southwest shore of King William Island, as belonging to engineer John Gregory, who sailed aboard the HMS Erebus.

The matching DNA came from one of Gregory's living descendants, a great-great-great grandson who lives in Port Elizabeth, South Africa, and bears the same name — Jonathan Gregory.

The identification makes explorer Gregory's story clearer than all of the others: He survived for three years on the ice-locked ship and died about 47 miles (75 kilometers) south at Erebus Bay while trying to escape.

"Having John Gregory's remains being the first to be identified via genetic analysis is an incredible day for our family, as well as all those interested in the ill-fated Franklin expedition," Gregory's great-great-great grandson said in the statement. "The whole Gregory family is extremely grateful to the entire research team for their dedication and hard work, which is so critical in unlocking pieces of history that have been frozen in time for so long."

The researchers, in turn, were grateful for Gregory's family for providing DNA samples and sharing their family's history, study co-author Douglas Stenton, an adjunct professor of anthropology at the University of Waterloo, said in the statement. "We'd like to encourage other descendants of members of the Franklin expedition to contact our team to see if their DNA can be used to identify the other 26 individuals."

The findings were published April 28 in the journal Polar Record.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.