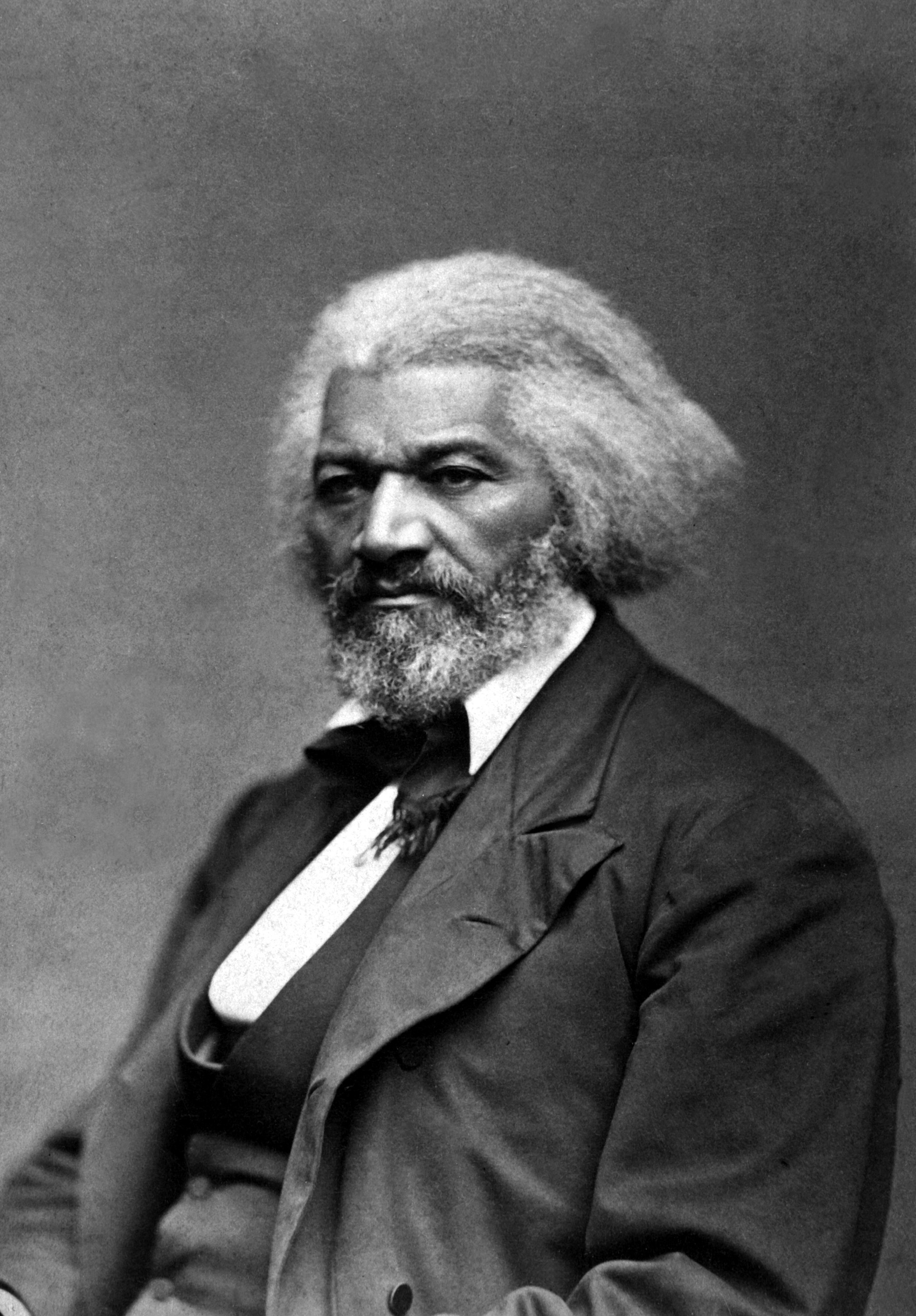

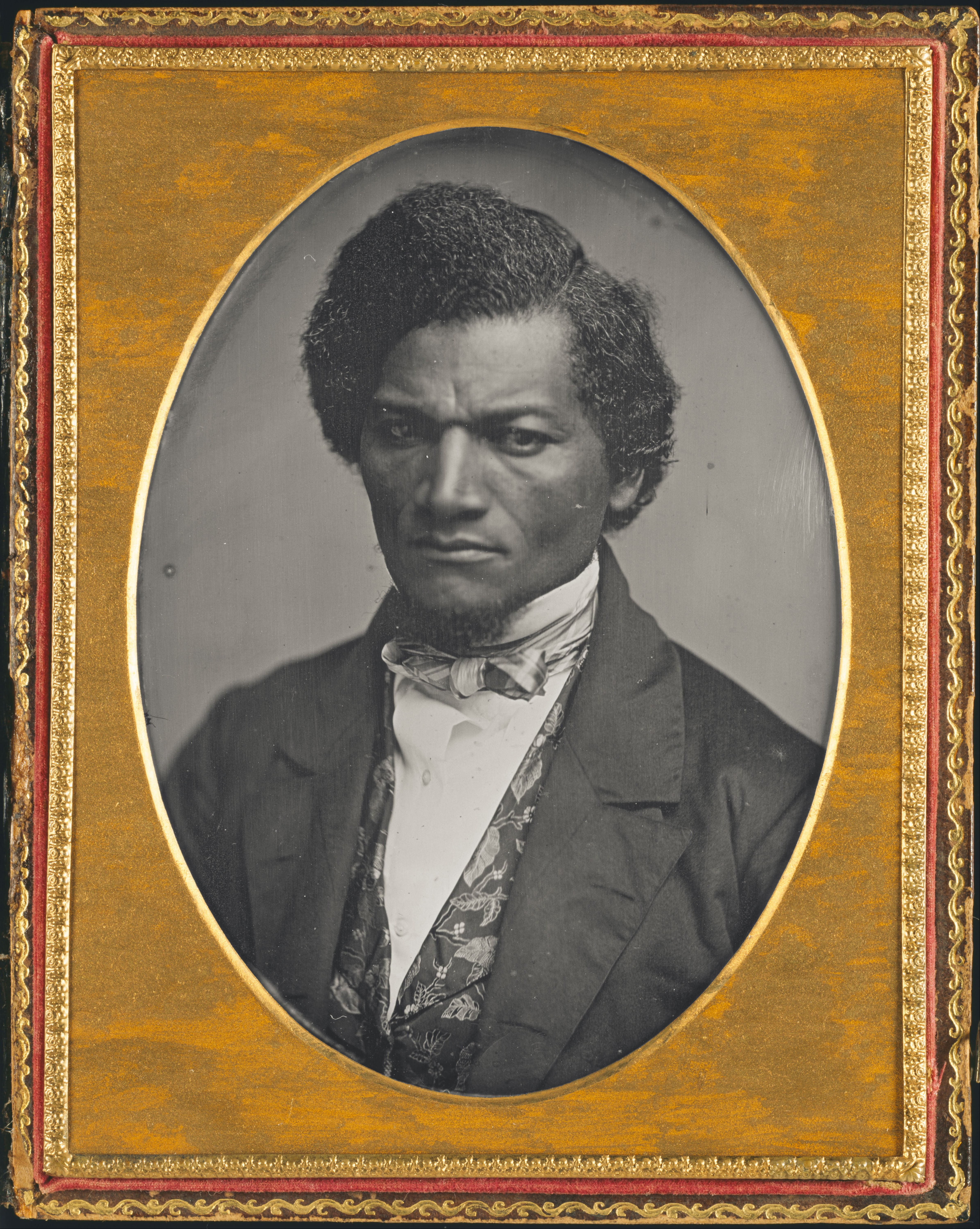

Frederick Douglass: The slave who became a statesman

The remarkable rise of Frederick Douglass, an agitator, reformer, orator, writer, artist and former slave.

Though he started life as a slave, Frederick Douglass became an abolitionist, orator, writer, statesman and ambassador. He liberated himself in 1838 and in 1845 published his first autobiography, "Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave," (The Anti-Slavery Office, 1845). The book, alongside his work for the abolitionist movement and the Underground Railroad, helped him become one of the most famous African American men of his era.

Born into slavery

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born around February 1818, although no records exist of the exact date) in Talbot County, Maryland. His mother was sent away to another plantation when he was a baby, and he saw her only a handful of times in the dark of night, when she would walk 12 miles to visit him. She died when he was seven years old.

Douglass was moved several times throughout his childhood, living on several Maryland farms and in households in the city of Baltimore. Douglass would later claim in his autobiography that his move to Baltimore "laid the foundation, and opened the gateway, to all my subsequent prosperity."

Related: 4 myths about the history of American slavery

One slaveholder, Sophia Auld, took a great interest in Douglass when he was 12 and taught him the alphabet, but her husband disapproved of teaching slaves to read and write. Eventually, Auld ceased her lessons and hid his reading materials.

But Douglass continued to find ways to learn, trading bread with street children for reading lessons. The more he read, the more tools he gained to question and condemn slavery. By 1834, while working on a new plantation, Douglass set up a secret Sunday school where around 40 slaves would gather and learn to read the New Testament. After neighboring plantation owners became aware of these clandestine meetings, they attacked the group with stones and clubs, permanently dispersing the school.

In 1837, Douglass met Anna Murray, a free Black woman in Baltimore who was five years his senior. The pair quickly fell in love and Murray encouraged him to escape. The following year, in 1838, aged 20, Douglass made his break from the shackles of slavery.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Escape and the abolitionist movement

In under 24 hours Douglass traveled from Maryland, a slave state, to New York, a free state, boarding northbound trains, ferries, and steamboats. Along the way, Douglass even disguised himself in a sailor’s uniform to avoid detection. Upon setting foot in New York, Douglass was free to decide the direction of his own life for the first time. Murray joined him and they were quickly married, settling on the new name "Douglass." According to his autobiography, the new surname was inspired by Sir Walter Scott’s poem "The Lady of the Lake."

Moving between abolitionist stronghold towns in Massachusetts, the pair became active members of the church community attended by many prominent former slaves, including Sojourner Truth and later Harriet Tubman.

By 1839 Douglass was a licensed preacher, a role in which he honed his speaking skills. He was also an active attendee of abolitionist meetings and, at age 23, gave his first anti-slavery speech at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society Convention in Nantucket.

Related: What shaped Martin Luther King Jr.'s prophetic voice?

As one of few men to have escaped slavery with a willingness and ability to speak about his experiences, Douglass became a living embodiment of the impacts of slavery and an image of Black stature and intellect.

In an interview with PBS, historian David W. Blight, author of “Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom,” (Simon & Schuster, 2018), claimed that certain white abolitionists "wanted Douglass to simply get up and tell his story, to tell his narrative on the platform. They didn't want him to speak about Northern racism, to take on the whole picture of the anti-slavery movement as much as he did." This strained Douglass’ relationships with some other major abolitionists. Nevertheless, Douglass continued to recognize the power of challenging and reshaping harmful caricatures of Black people.

Douglass published his autobiography in 1845. Its subsequent success and acclaim led historian James Matlack to describe it as "the best-known and most influential slave narrative written in America" in a 1960 article from the journal Phylon.

As his fame grew — and as threats to his life and freedom from pro-slavery groups also grew, according to a memoir written by his daughter Rosetta Douglass Sprague in a 1923 edition of The Journal of Negro History — Douglass left his family and spent two years touring Ireland and Britain between 1845 and 1847. He spent the trip lecturing and meeting with members of Britain’s abolition movement. It was during this time that Douglass gained legal freedom and protection from recapture, with English acquaintances raising the funds to officially buy his freedom.

He returned to the U.S. with an additional £500 donated by English supporters and used it to set up his first abolitionist newspaper, "The North Star." Alongside this, he and his wife were active in the Underground Railroad, taking over 400 escaped slaves into their home.

Women's suffrage

Douglass was an advocate for dialogue and alliances across ideological divides. Notably, he was a supporter of women’s suffrage campaigns and was a close friend of women's suffrage campaigners Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony.

Related: Women's suffrage anniversary: Which countries led the way?

However, Douglass came into conflict with the women's suffrage movement through his support of the Fifteenth Amendment, passed on Feb. 26, 1869, which gave Black men the right to vote, but not women. Douglass's stance on the Fifteenth Amendment, and the opposition of some women's suffrage campaigners to Black suffrage, caused a rift within the American Equal Rights Association (AERA), which broke up in 1869, according to the Arlington Public Library.

Douglass continued to argue in his book "Life and Times of Frederick Douglass," (De Wolfe, Fiske & Co. 1892) that the disenfranchisement of women was equally damaging to the United States as the denial of Black citizens' right to vote. "I would give woman a vote, give her a motive to qualify herself to vote, precisely as I insisted upon giving the colored man the right to vote," he wrote.

The “Fourth of July” speech

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? ...To him, your celebration is a sham.

Frederick Douglass

On July 5, 1852, Douglass gave one of his most famous speeches, "What to the slave is the Fourth of July," to the Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society of Rochester, New York.

"I do not hesitate to declare, with all my soul, that the character and conduct of this nation never looked blacker to me than on this 4th of July!" he said. " What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham."

In the speech, Douglass made the case that positive statements about the U.S. and its independence were an affront to enslaved people, who could not share in the nation’s celebration of liberty.

Political career

Douglass published three versions of his life story, in 1845, 1855 and 1881 (with a revised edition in 1892). By the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, he was one of the most famous Black men in the U.S. as well as both an ardent supporter and honest critic of Abraham Lincoln. Later, during the Reconstruction era, Douglass received several political appointments, including President of the Freedman’s Savings Bank.

Related: What if Lincoln had lived?

Douglass supported Ulysses S. Grant's 1868 presidential campaign amid a violent period of backlash against newly emancipated slaves and the rise of the Ku Klux Klan. Later, in 1889, President Harrison appointed him as the U.S. Minister Resident and Consul-General to Haiti, and the chargé d’affaires to Santo Domingo.

In 1872 he became the first African American to be nominated for vice president of the United States (though without his knowledge or approval).

Later years and legacy

The end of Douglass' life was turbulent. According to the U.S. Library of Congress timeline of his life, he was forced to flee into exile after being accused of collaborating with radical abolitionists who attempted to raid Harpers Ferry in 1859. In 1872, per the New York Times, his home was burned down in an arson attack, causing him to move to Washington, D.C. with his family.

His family life also became a focus of gossip and scandal: According to Smithsonian magazine, he was rumored to have had two affairs with white women while his wife Anna was alive. She died in 1880, and Douglass was married again less than two years later to Helen Pitts, a white suffragist and abolitionist 20 years his junior.

His affairs and controversial second marriage tainted Douglass’ reputation. Later accounts like Rosetta Douglass Sprague’s memories of her mother cast a sympathetic light on their mother, Anna Douglass, who remained Douglass’ most ardent supporter through controversy and infidelity.

Douglass continued touring and traveling, speaking and campaigning into his final days — to his very last moments. After receiving a standing ovation for a speech on women’s suffrage in 1895, the 77-year-old Douglass collapsed from a heart attack. Thousands passed by his coffin to pay their respects, and he continues to be honored by countless statues, remembrances and plaques across the globe.

This article was adapted from a previous version published in All About History magazine, a Future Ltd. publication. To learn more about some of history's most incredible stories, subscribe to All About History magazine.

All About History is the only history magazine that is as entertaining as it is educational. Bringing History to life for readers of all ages.