'Dyson sphere' legacy: Freeman Dyson's wild alien megastructure idea will live forever

Freeman Dyson's alien-hunting idea has worked its way into the culture.

Freeman Dyson may be gone, but his famous alien-hunting idea will likely persist far into the future.

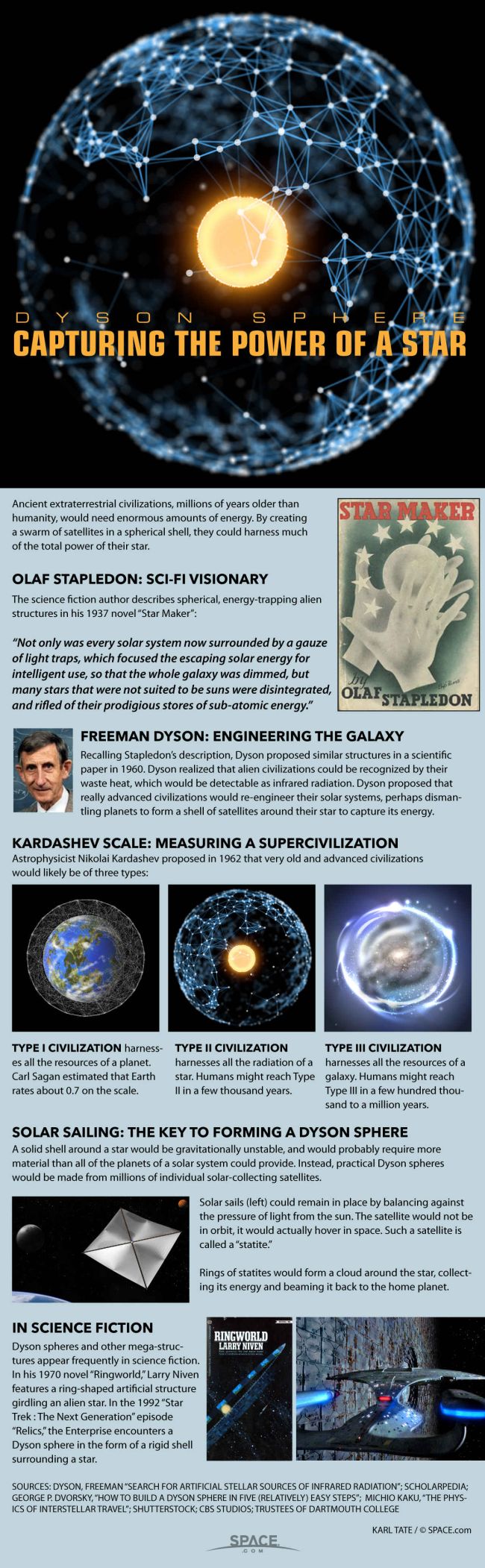

Dyson, a quantum physicist who died at age 96 on Feb. 28, recalled in a 2003 interview just how he first advanced his concept of a "Dyson sphere," which could betray the existence of an advanced alien civilization. It was via a 1960 article in the journal Science called "Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infrared Radiation."

Dyson wrote the article just as scientists were beginning to search for signs of alien intelligence using radio telescopes. The 1960 piece noted, Dyson said, that radio is a great medium for searching — but only if aliens are willing to communicate. If the aliens remained silent, you would need to look for their heat waste from space, using infrared sensors.

Related: What is a Dyson sphere?

"Unfortunately, I added to the end of that remark that what we're looking for is an artificial biosphere," Dyson said in the 45-minute interview from 2003, which is on YouTube's MeaningofLife.tv channel.

He was imagining a swarm of objects that could masquerade as dust from a distance, he added, but his choice of words sparked an accidental legacy.

"The science fiction writers then got hold of it and imagined the biosphere means a sphere — it has to be some big, round ball. And so, out of that, there came these weird notions, which ended up on 'Star Trek.'"

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One of Dyson's daughters sent the physicist a videotape of a 1987 episode of "Star Trek: The Next Generation" called "Relics," Dyson said. The plot follows a distress call heard by the famous USS Enterprise starship; fans of the series may recall this as a crossover episode with "Star Trek: The Original Series" star Montgomery "Scotty" Scott (played by James Doohan).

The crew warps in space to the source of the call and discovers an immense Dyson sphere — which is indeed portrayed as a solid spherical object — surrounding a star. If we were to place this sphere in our own solar system, it would be so large that it would extend almost as far as the orbit of Venus, according to "Star Trek" fan site Memory Alpha. (In the episode, the Dyson sphere is explained as being as large as two-thirds of Earth's orbital diameter, and Venus' orbit is a little beyond that point.)

"I watched it [the episode], and oh yes, it's very clearly labeled [as a Dyson sphere]; it was sort of fun to watch it, but it was all nonsense," Dyson said in the interview. He added that the name "Dyson sphere" is a misnomer, as he originally got the inspiration from 1930s science fiction writer Olaf Stapledon, who first wrote about the concept in the novel "Star Maker."

Related: The evolution of 'Star Trek' (infographic)

Depictions such as the one in "Relics" have given us the current popular understanding of a Dyson sphere, which envisions a mammoth structure surrounding a star to capture as much of its energy as possible.

So imagine everyone's surprise when in 2015 scientists announced a star that was exhibiting strange behavior, fluctuating with no apparent pattern. Many ideas were put forth by the discovery team, including the idea that perhaps this was a real-life Dyson sphere in action.

This star (called KIC 8462852) is otherwise an unremarkable object. It is a bit hotter and larger than Earth's sun and is no great distance from us in cosmic terms, sitting about 1,480 light-years away from our planet in the constellation Cygnus.

The researchers picked up on the star's weird light fluctuations using a mission designed to stare at stars for years at a time to hunt exoplanets. The star showed up in data from NASA's Kepler space telescope, displaying sudden dimmings of up to 22% for a few days or a week at a time. In fact, it wasn't astronomers who first saw the pattern; it was citizen scientists examining Kepler's work through the crowdsourced Planet Hunters project on Zooniverse.org.

The 2015 research team, led by astrophysicist Tabetha "Tabby" Boyajian (then at Yale University, and now at Louisiana State University), initially could not explain the dimmings and brightenings through natural phenomena such as dust.

Their discovery paper in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society went viral. The star was nicknamed Tabby's star (and, later, Boyajian's star) after the discoverer; Boyajian credits the Dyson sphere idea to one of her colleagues and not herself, she told Space.com.

One of the best results of the paper was that it promoted more collaboration between astronomers and those who search for signs of extraterrestrial intelligence, she said in an interview. "We're all looking at the same sky, at the same targets, but we don't mix that well. We don't go to the same conferences, and we don't read the same papers," she added.

Another happy side effect of the publicity was that Boyajian's team got time on the Allen Telescope Array (ATA), a network of 42 radio dishes in Northern California operated by the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) Institute. Most telescopes have limited time available for observations and, as such, teams need to write proposals for how they plan to use the time. These proposals are then peer reviewed by other astronomers to determine who will get the telescope for a predetermined period of time.

Related: 13 ways to hunt intelligent aliens

Boyajian and colleagues wrote a one-page proposal that was initially turned down, but then they received an invitation to use the ATA anyway "because it was good publicity," she said. The bonus telescope time helped Boyajian's team catch a break. In 2017, the star dimmed and brightened several times while the telescope was aimed at it, as her team discussed in a paper published in 2018 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

"This was really exciting, because we were able to watch this in real time and trigger a bunch of other observations to really study what was going on in front of the star," Boyajian recalled. This resulted, she added, in a "whole boatload of data" as the team examined the star's luminosity in different colors of light.

That's when the team discovered that more blue light was blocked than red light, which suggests the blockage cannot be a solid object like a perfect sci-fi Dyson sphere, Boyajian said. "You would imagine if you had some solid object go in front of a light source, it would block all of it equally," she explained.

By 2019, some astronomers favored explanations such as swarms of comets or clumped clouds of dust for the star's weird behavior, but Boyajian maintains the star merits more study. (In fact, she is working on a few new papers about KIC 8462852.)

"We still have yet to pin a natural explanation on it," she said. "Typically, when you have dust surrounding a star, you also have an infrared excess, [meaning] it glows in the infrared, in longer wavelengths. We don't see that at all.

"On top of these observations," she continued, "we have another very peculiar issue with the star, in that it not only has these short-term drops in its brightness, but it also has this very long-term variability going back over a century. [Before,] this star was over 20% brighter than it is today. It just threw a wrench in everything."

Some people are sticking to the Dyson sphere hypothesis, Boyajian said, invoking the idea that perhaps construction is changing the patterns of light over time. She added that until the team can find another star like this one to do comparison studies, KIC 8462852 may remain a mystery.

"Nature is a lot more creative than we are," she said, suggesting that perhaps NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) could pick up a signal in one of the zones of the sky it studies, as long as the signal happens within a period of 300 days. Kepler, for comparison, stared at the same patch of sky for four years, including a two-year period when KIC 8462852 was dormant in between its sudden dimmings.

TESS rotates between different areas of the sky every 27 days and switches hemisphere views from south to north (or vice versa) roughly once a year. Part of its field of view overlaps between the rotation sequence, allowing for a small zone that can be studied for several months at a time.

A smaller possibility of an "aha" signal could come from Europe's Gaia mission, which is monitoring a billion stars for properties including movement and luminosity changes, Boyajian said. Since Gaia constantly moves between different portions of the sky, it cannot do constant monitoring — meaning that if it spots something interesting, any observations would be brief and another mission would be needed for follow-up.

Amid the international excitement about her find, Boyajian received an offer from an acquaintance of Dyson to put her in touch with the famed physicist, when Dyson was about 91 years old. She wrote Dyson an email briefly explaining her work, and how the scientists were struggling to explain the behavior of KIC 8462852. To her delight, Dyson responded only 15 minutes later with congratulations.

"This is a new kind of creature in the celestial zoo, and it will turn out to be important," read part of Dyson's email to Boyajian. He compared her team's find to the discovery of gamma-ray bursts in the 1960s by the United States' Vela satellites, which were designed primarily to detect nuclear tests.

Dyson wrote in that email that one of the team members behind the gamma-ray burst discovery confided in him about the find and said the researchers "hesitated to publish the discovery" because "the bursts seemed to defy the laws of physics." (In just a few seconds, gamma-ray bursts can produce as much energy as the sun will produce in its 10-billion-year lifespan.)

Dyson encouraged the researchers to show what they had so far, with faith that, over time, some explanation would come forth. So the publication went ahead, sparking various competing explanations for decades. A generation later, in 1991, NASA's Compton Gamma Ray Observatory launched and discovered an average of one burst a day, emanating from all over the sky.

Compton discovered that the bursts come in two flavors — longer lived and shorter lived — and it wasn't until 2005 that the sources of both were pinned down. Long-lived bursts come from very powerful supernova explosions known as hypernovas. Short-lived bursts occur when two remnant star corpses (called neutron stars) crash into each other and form a black hole, or a black hole swallows a neutron star.

"It was just a lovely email," Boyajian said of Dyson's words. His theories remain relevant to astronomy, she added, as scientists grapple with the ongoing question of why we have not found intelligent aliens yet, given the size of our universe and the decades of dedicated searching by Earthlings.

"Even though we found dozens, then hundreds, then thousands of planets that are everywhere, there is no sign of intelligent life out there with a megaphone screaming at us, 'We're here,'" Boyajian said.

- Fermi Paradox: Where are all the aliens?

- 10 exoplanets that could host alien life

- Warp drive & transporters: How 'Star Trek' technology works (infographic)

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save at least 56% with our latest magazine deal!

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our solar system and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.