635 million-year-old fossil is the oldest known land fungus

Its tiny tendrils are 1/10 the width of a human hair.

The oldest evidence of land fungus may be a wee microfossil that's 635 million years old, found in a cave in southern China.

Too small to be seen with the naked eye, this remarkable find pushes back the appearance of terrestrial fungus by about 240 million years to a period known as "snowball Earth" when the planet was locked in ice from 750 million to 580 million years ago.

The presence of land fungus at this critical point may have helped Earth to transition from a frozen ice ball to a planet with a variety of ecosystems that could host diverse life-forms, scientists wrote in a new study. By breaking down minerals and organic matter and recycling nutrients into the atmosphere and ocean, ancient fungus could have played an important part in reshaping Earth's geochemistry, creating more hospitable conditions that paved the way for terrestrial plants and animals to eventually emerge and thrive.

Related: Images: The oldest fossils on Earth

Scientists discovered the fossilized threadlike filaments — a trademark of fungus structures — in sedimentary rocks from China's Doushantuo Formation in Guizhou Province, dating to the Ediacaran period (about 635 million to 541 million years ago). Identifying rocks that might contain microscopic fossils takes luck as well as skill, said study co-author Shuhai Xiao, a professor of geosciences with the Virginia Tech College of Science (VT) in Blacksburgh, Virginia.

"There's an element of serendipity, but there's also an element of experience and expectation. Having worked with microfossils, one knows what kind of rocks to look at," Xiao told Live Science. For example, rocks must be fine-grained, because the fossils are so small. Color can also provide clues; organic carbon in microfossils can make fossil-bearing rocks look darker than rocks that don't contain fossils.

"But it's not error-proof; most times, we slice a rock, and we don't find anything. There's maybe a 10% success rate," Xiao said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Thinly sliced

To find the fossils, the study authors ground slices of rock thin enough for light to penetrate, measuring no more than 0.002 inches (50 micrometers) thick. Powerful microscopes revealed the fungus's tiny tendrils, which were just a few micrometers in diameter — about 1/10 the width of a human hair. Under the microscopes, traces of organic carbon in the fossils were darker than the rock surrounding it.

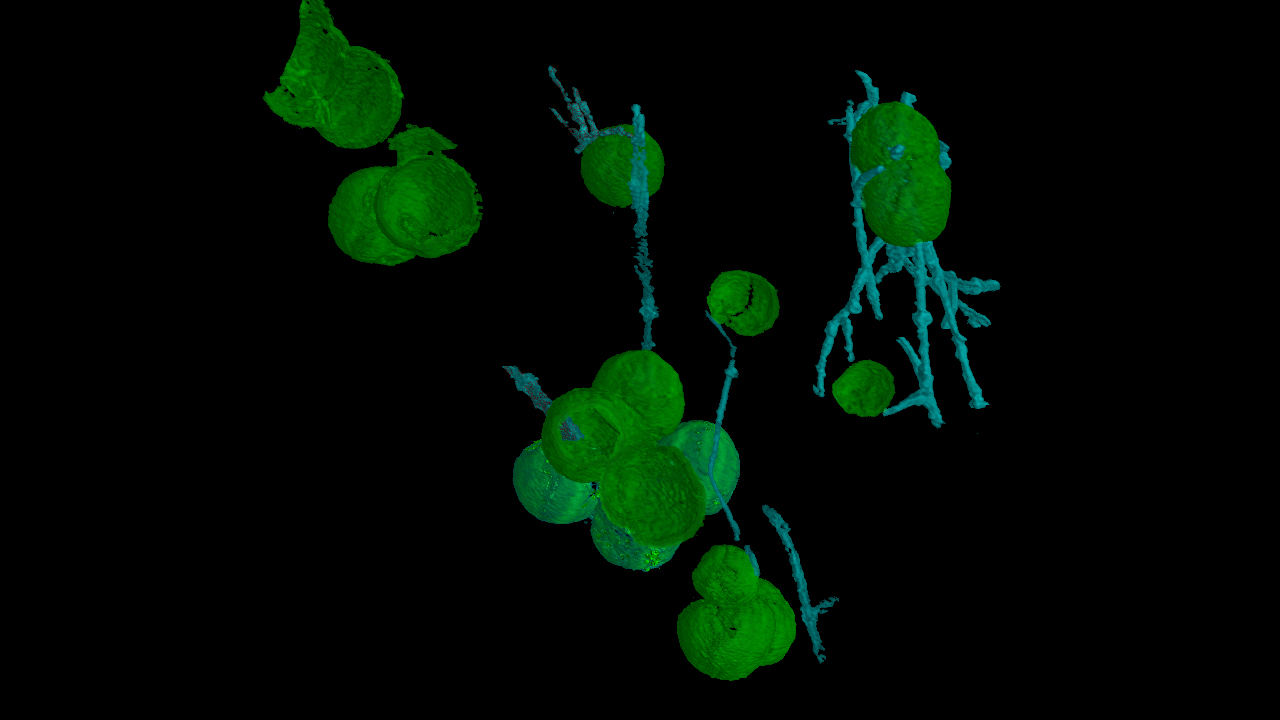

The researchers also used more advanced microscopy to examine the fossils and build digital copies of their structures. Luckily, many of those structures "were excellently preserved in three-dimensions," lead study author Tian Gan, a doctoral candidate at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing and a visiting scholar at VT, told Live Science in an email.

Those branching filaments told the researchers that the fossils were biological in origin, rather than mineral. Though some types of bacteria also produce branches, the closest analogs for these types of filaments are fungal, and small spheres in the fossil "could be interpreted as fungal spores," supporting the hypothesis that these microorganisms were a type of fungus, the scientists wrote.

Ancient life

Fossil evidence of the earliest organisms on Earth is exceptionally rare, but this microfossil and other recent finds are helping researchers to slowly piece together important clues about when life first appeared.

The oldest evidence of marine fungus, described in 2019 from rocks found in Canada, dates to about a billion years ago; the oldest forest, described in 2020 from fossilized roots in upstate New York, is 386 million years old; and the oldest known animal — a bizarre, oval-shaped creature called Dickinsonia — is about 558 million years old (fossils that were once thought to represent older animals were recently attributed to ancient algae, Live Science reported in December 2020).

Fossilized structures from Canada that may have been built by microbes between 3.77 billion and 4.29 billion years ago represent one of the oldest possible examples of life on Earth. Other structures preserved in Greenland rock are also thought to have microbial origins, and are 3.7 billion years old. Yet another fossil from western Australia may contain microbes estimated to be 3.5 billion years old, though some scientists have argued that geothermal activity could have altered chemicals in the rock to make them resemble biological traces, Live Science previously reported.

Scientists first linked terrestrial fungus to the appearance of land plants, based on fossils from the Rhynie cherts in Scotland that preserve plants and fungi together and date to about 410 million years ago, Xiao said. In those fossils, "plants and fungi have already established some sort of ecological relationship," he explained.

However, fungus fossils that predated the earliest known plants previously hinted that terrestrial fungus appeared first, about 450 million years ago, "and now we extend that back to 635 million years ago," Xiao said.

The findings were published online Jan. 28 in the journal Nature Communications.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.