2 geomagnetic storms will lash Earth today, but don't worry (too much)

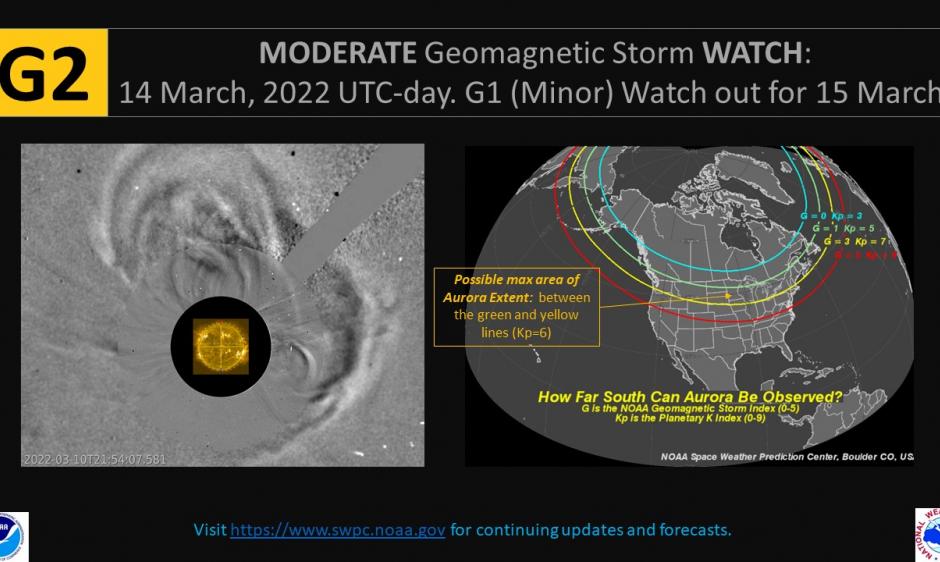

Auroras could be seen as far south as Idaho and New York, according to NOAA.

Earth could be hit by a series of mild geomagnetic storms on Monday and Tuesday (March 14 and 15) after a moderate solar flare blasted out of the sun's atmosphere several days ago, according to government weather agencies in the U.S. and U.K.

The storms aren't likely to cause any harm on Earth, save for possibly muddling radio transmissions and affecting power grid stability at high latitudes — however, the aurora borealis could be seen at lower latitudes that usual, possibly as far south as New York and Idaho in the U.S., according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

NOAA categorized the incoming storms as a category G2 on Monday and a G1 on Tuesday, based on the agency's five-level solar storm scale (G5 being the most extreme). Earth experiences more than 2,000 category G1 and G2 solar storms every decade, according to NOAA, and is currently in the midst of a mild solar storm streak; the latest G2 storm grazed by Earth on Sunday (March 13), passing early in the morning without much trouble.

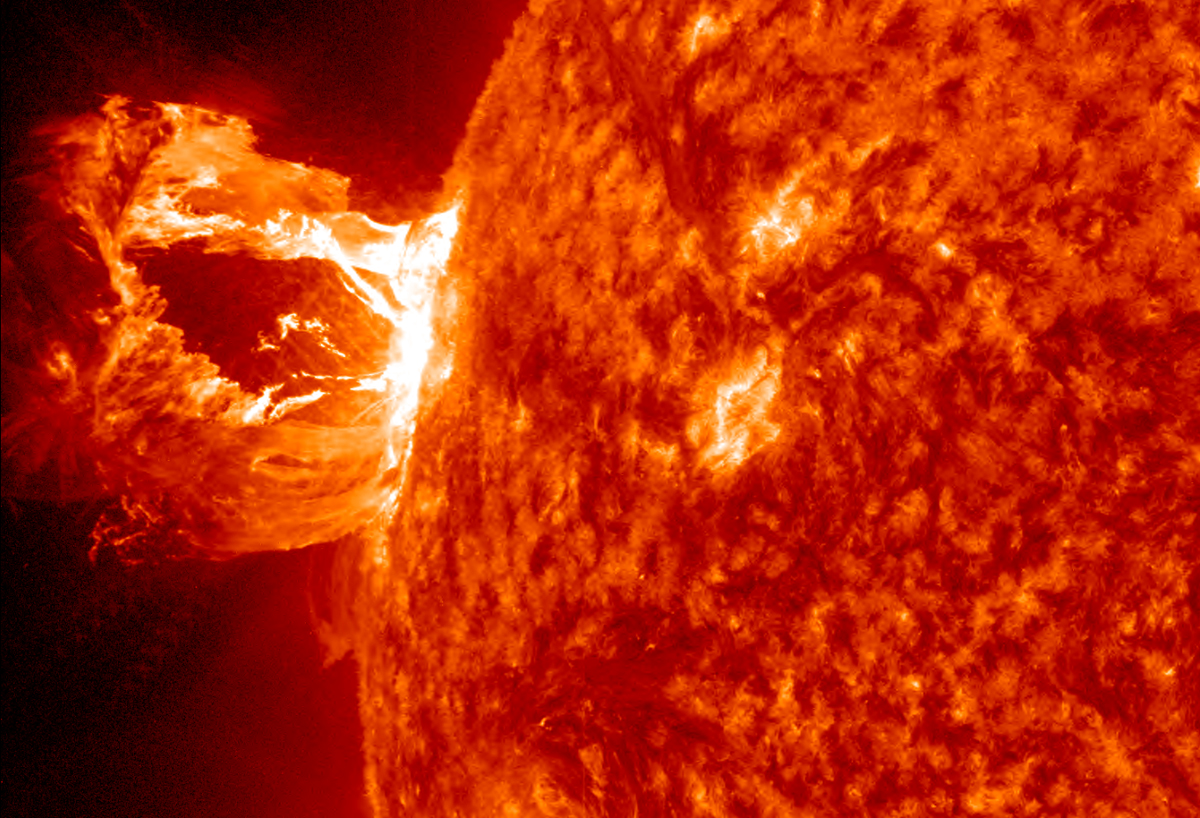

Like all geomagnetic storms, the predicted events on Monday and Tuesday stem from an outburst of charged particles leaving the sun's outermost atmosphere, or corona. These outbursts, known as coronal mass ejections (CMEs) occur when magnetic field lines in the sun's atmosphere tangle and snap, ejecting bursts of plasma and magnetic field into space.

These great globs of particles sail across the solar system on the sun's solar wind, occasionally passing right over Earth, and compressing our planet's magnetic shield in the process. That compression triggers the geomagnetic storm.

The vast majority of storms are mild, only tampering with technology in space or at very high latitudes, according to NOAA. But larger CMEs can trigger much more extreme storms – such as the infamous 1859 Carrington Event, which induced such strong electrical currents that telegraph equipment to burst into flame, according to NASA. Some scientists have warned that another solar storm of that size could plunge Earth into an "internet apocalypse," knocking nations offline for weeks or months, Live Science previously reported.

Solar storms are also responsible for the aurora. When CMEs slam into Earth's atmosphere, solar plasma ionizes the ambient oxygen and nitrogen molecules there, causing them to glow. Powerful CMEs can push the aurora down to much more southerly latitudes than usual; during the Carrington Event, the northern lights were visible on Hawaii, according to NASA.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The sun has been spitting out CMEs almost every day since mid-January, according to NOAA (though not all of them have crossed paths with Earth). Such is to be expected as we head toward the part of the sun's 11-year activity cycle known as Solar Maximum – the point where solar storms and CMEs are most active. The next Solar Maximum will hit around July 2025, with solar activity likely to increase all the while.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.