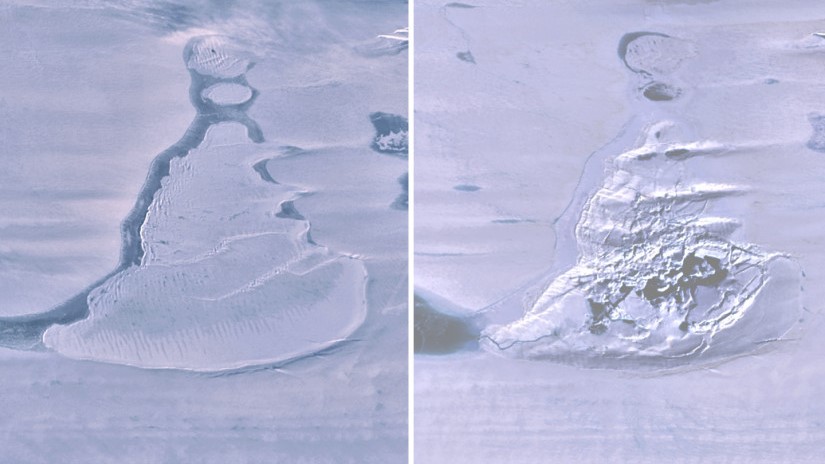

Enormous Antarctic lake vanishes in 3 days

The lake disappeared by creating an enormous fissure in the ice beneath it.

An enormous, ice-covered lake in Antarctica vanished suddenly, and scientists are worried it could happen again.

In this disappearing act, which researchers say occurred during the 2019 winter on the Amery Ice Shelf in East Antarctica, an estimated 21 billion to 26 billion cubic feet (600 million to 750 million cubic meters) of water — roughly twice the volume of San Diego Bay — drained into the ocean.

The scientists who used satellite observations to capture the shocking vanishing act say the lake drained in roughly three days after the ice shelf beneath it gave way.

Related: 10 signs Earth's climate is off the rails

"We believe the weight of water accumulated in this deep lake opened a fissure in the ice shelf beneath the lake, a process known as hydrofracture, causing the water to drain away to the ocean below," Roland Warner, a glaciologist at the University of Tasmania and lead author of a new study describing the event, said in a statement. He added that once the water was released, "the flow into the ocean beneath would have been like the flow over Niagara Falls, so it would have been an impressive sight."

Hydrofracturing (a natural process using the same physical principles as hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, used to extract oil or gas from bedrock) occurs when water — which is denser and, therefore, heavier than ice — rips open gigantic cracks in ice sheets — and then drains into the sea. This leaves behind a gigantic fissure which compromises the structural integrity of the sheet as a whole. As meltwater lakes and streams multiply across the surface of Antarctica, researchers are concerned that growing volumes of surface meltwater could cause more hydrofracturing events, which could cause ice shelves, including the parts which are anchored to the ground, to collapse, thus elevating sea levels above current projections.

"Antarctic surface melting has been projected to double by 2050, raising concerns about the stability of other ice shelves," the team wrote in their study, which was published June 23 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. "Processes such as hydrofracture and flexure remain understudied, and ice-sheet models do not yet include realistic treatment of these processes." (Flexure is the flexing of the underside of the ice-shelf by the weight of the meltwater above it, and another potential cause of the break-up of ice-shelves.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Warner and colleagues took aerial measurements of the dramatic outpouring of the lake with observations from NASA's ICESat-2 satellite, which takes readings by bouncing pulses of laser light off a target of interest and measuring the time it takes for the pulses to be reflected. From this time delay, scientists are able to calculate the elevation of a target.

After the deluge, the region surrounding the lake, now free of the water's weight, rose 118 feet (36 meters) from its original position, and there was an enormous fracture — called an ice doline — that carved out an area of about 4.25 square miles (11 square kilometers) along the lake bed. During the summer of 2020, the lake refilled with water in just a few days, with a peak flow of 35 million cubic feet (1 million cubic meters) per day. Whether this water will create new fractures to vanish into, or is already disappearing through the old fracture and out into the ocean, is unclear, according to the researchers.

"It might accumulate meltwater again or drain to the ocean more frequently," Warner said. "It does appear that the fracture reopened briefly during the 2020 summer melt season, so it is certainly a system to watch. This event does raise new questions about how common these deep ice-covered lakes are on ice shelves and how they evolve."

Originally published on Live Science.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.