A newly discovered crescent of galaxies spanning 3.3 billion light-years is among the largest known structures in the universe and challenges some of astronomers' most basic assumptions about the cosmos.

The epic arrangement, called the Giant Arc, consists of galaxies, galactic clusters, and lots of gas and dust. It is located 9.2 billion light-years away and stretches across roughly a 15th of the observable universe.

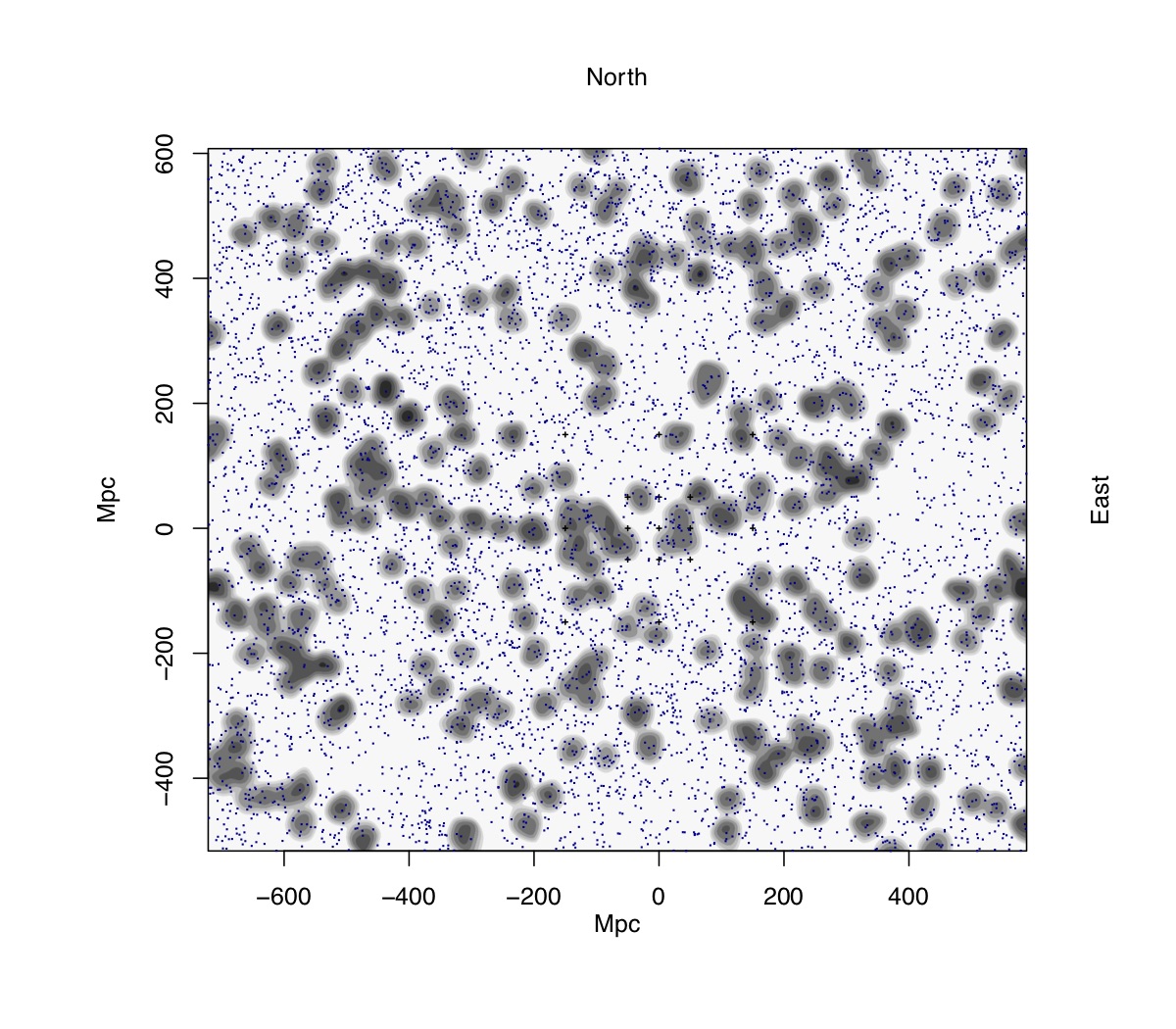

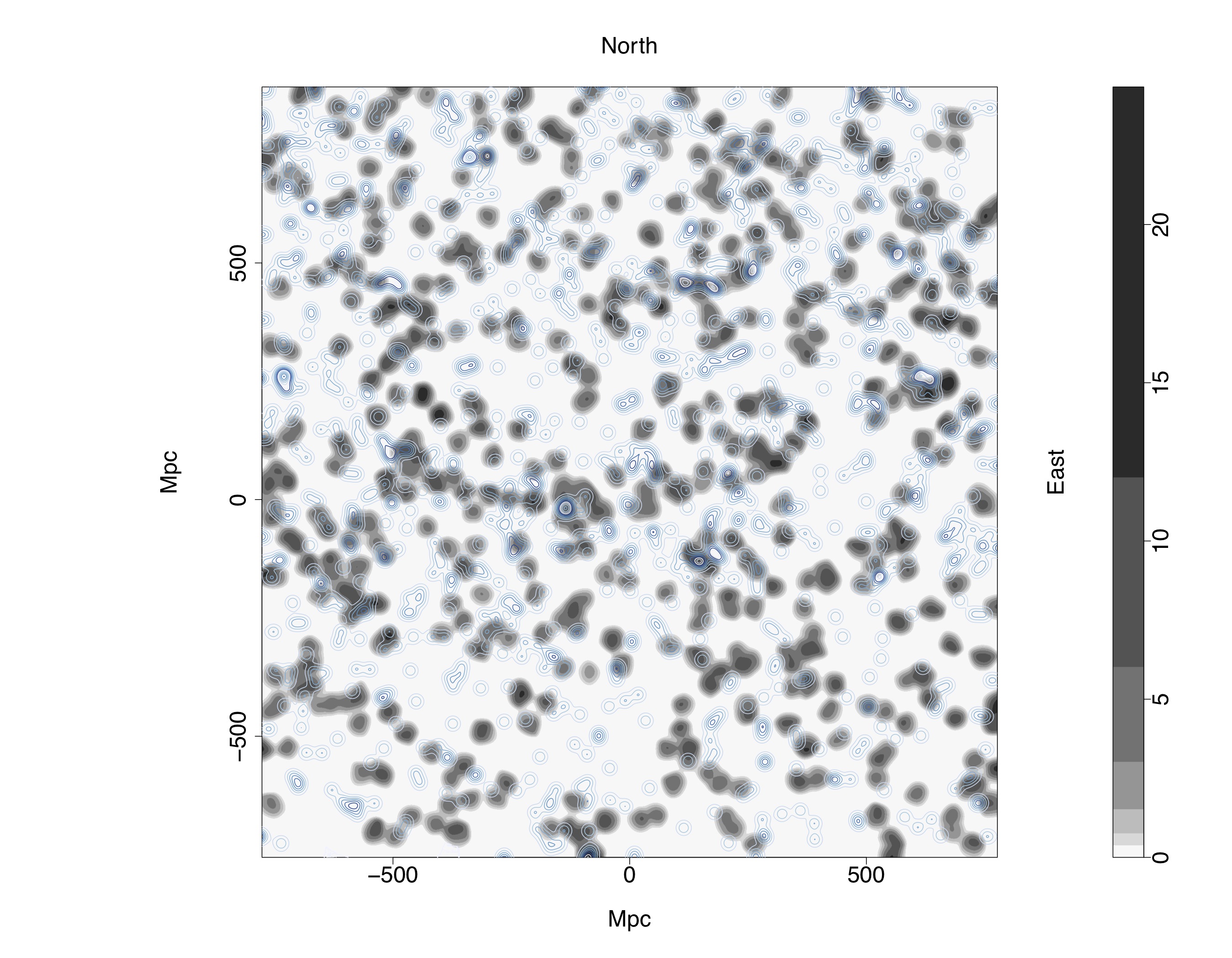

Its discovery was "serendipitous," Alexia Lopez, a doctoral candidate in cosmology at the University of Central Lancashire (UCLan) in the U.K., told Live Science. Lopez was assembling maps of objects in the night sky using the light from about 120,000 quasars — distant bright cores of galaxies where supermassive black holes are consuming material and spewing out energy.

Related content: Cosmic record holders: The 12 biggest objects in the universe

As this light passes through matter between us and the quasars, it is absorbed by different elements, leaving telltale traces that can give researchers important information. In particular, Lopez used marks left by magnesium to determine the distance to the intervening gas and dust, as well as the material’s position in the night sky.

In this way, the quasars act "like spotlights in a dark room, illuminating this intervening matter," Lopez said.

In the midst of the cosmic maps, a structure began to emerge. "It was sort of a hint of a big arc," Lopez said. "I remember going to Roger [Clowes] and saying 'Oh, look at this.'"

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Clowes, her doctoral adviser at UCLan, suggested further analysis to ensure it wasn't some chance alignment or a trick of the data. After doing two different statistical tests, the researchers determined that there was less than a 0.0003% probability the Giant Arc wasn't real. They presented their results on June 7 at the 238th virtual meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

But the finding, which will take its place in the list of biggest things in the cosmos, undermines a bedrock expectation about the universe. Astronomers have long adhered to what's known as the cosmological principle, which states that, at the largest scales, matter is more or less evenly distributed throughout space.

The Giant Arc bigger than other enormous assemblies, such as the Sloan Great Wall and the South Pole Wall, each of which are dwarfed by even larger cosmic features.

"There have been a number of large-scale structures discovered over the years," Clowes told Live Science. "They're so large, you wonder if they're compatible with the cosmological principle."

The fact that such colossal entities have clumped together in particular corners of the cosmos indicates that perhaps material isn’t distributed evenly around the universe.

But the current standard model of the universe is founded on the cosmological principle, Lopez added. "If we're finding it not to be true, maybe we need to start looking at a different set of theories or rules."

Lopez doesn't know what those theories would look like, though she mentioned the idea of modifying how gravity works on the largest scales, a possibility that has been popular with a small but loud contingent of scientists in recent years.

Daniel Pomarède, a cosmographer at Paris-Saclay University in France who co-discovered the South Pole Wall, agreed that the cosmological principle should dictate a theoretical limit to the size of cosmic entities.

Some research has suggested that structures should reach a certain size and then be unable to get larger, Pomarède told Live Science. "Instead, we keep finding these bigger and bigger structures."

Yet he isn't quite ready to toss out the cosmological principle, which has been used in models of the universe for about a century. "It would be very bold to say that it will be replaced by something else," he said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Adam Mann is a freelance journalist with over a decade of experience, specializing in astronomy and physics stories. He has a bachelor's degree in astrophysics from UC Berkeley. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, New York Times, National Geographic, Wall Street Journal, Wired, Nature, Science, and many other places. He lives in Oakland, California, where he enjoys riding his bike.