Giant, ostrich-like dinosaur and its smaller cousin roamed Mississippi during the late Cretaceous

A giant, ostrich-like dinosaur and its smaller cousin, also an ornithomimosaur, sprinted through what is now Mississippi about 85 million years ago.

Two ostrich-like dinosaurs — a towering paleo-beast that was among the largest of its kind, and its smaller, fierce cousin — sprinted through what is now Mississippi about 85 million years ago, during the Cretaceous period, new fossil finds reveal.

Scientists still don't know whether these fossils belong to two previously unknown species of ornithomimosaurs, which is Latin for "bird mimics." But the discovery of the remains is remarkable, given that the ancient landmass they once roamed, essentially what is now the eastern half of North America, has a poor dinosaur fossil record from the late Cretaceous that's chock-full of broken, hard-to-decipher bones, scientists wrote in a new study.

The finding fills a "critical gap" in the known range and biodiversity of this type of dinosaur from the region during the late Cretaceous (145 million to 66 million years ago), said study lead author Chinzorig Tsogtbaatar, a postdoctoral research scholar in the Department of Biological Sciences at North Carolina State University.

The fossils also document "the youngest occurrence of ornithomimosaurs in Appalachia," Tsogtbaatar told Live Science in an email.

Related: Tsunami from dinosaur-killing asteroid had mile-high waves and reached halfway across the world

Ornithomimosaurs are theropods — a group of bipedal, mostly meat-eating dinosaurs — making them distantly related to the mighty Tyrannosaurus rex. But unlike the hulking, tiny-armed T. rex, ornithomimosaurs were lightly built and sported long arms, powerful legs, small skulls and strong beaks — some with teeth and some without, according to the study, published online Wednesday (Oct. 19) in the journal PLOS One.

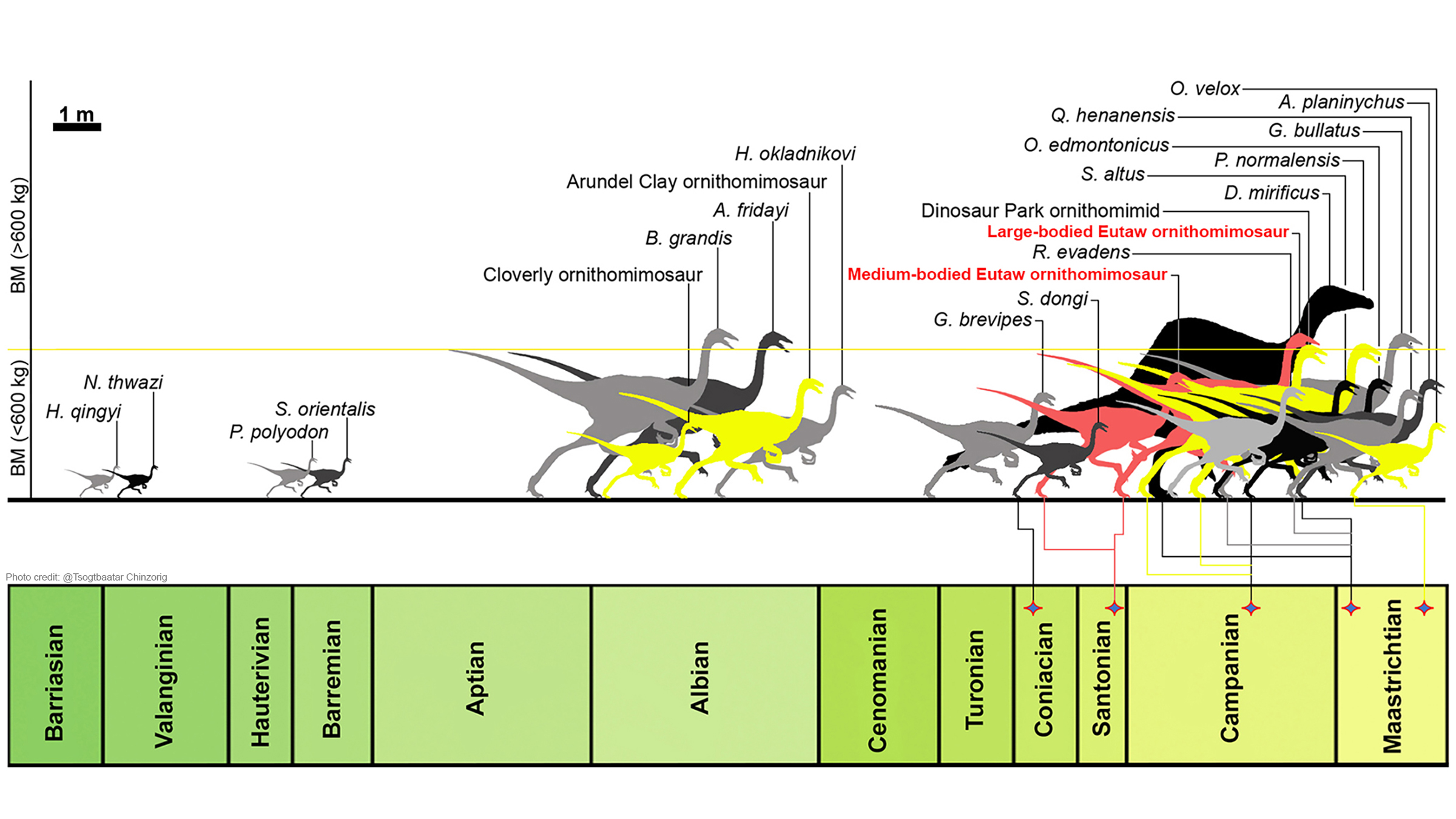

These omnivores ranged greatly in size, from the colossal Deinocheirus, which stood as tall as a three-story building and measured about 36 feet (11 meters) long, to pup-size pip-squeaks that were smaller than 3 feet (1 m) long, such as Nqwebasaurus and Pelecanimimus, said Tsogtbaatar, who is also at the Paleontology Research Lab at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The newly described fossils were unearthed near Luxapallila (also spelled Luxapalila) Creek in Lowndes County, Mississippi. After comparing the proportions of the fossils and the growth lines within the bones (like trees, dinosaur bones have lines associated with their ages and growth spurts), the researchers concluded that the bones likely belonged to two different ornithomimosaur species — one very large, and the other medium-size.

The larger of the two creatures likely weighed over 1,760 pounds (800 kilograms), and was probably about 10 years old and still growing when it died. This weighty size makes it one of the largest ornithomimosaurs on record, the researchers said.

The medium-size dino was likely about 20% to 50% the mass of its bigger counterpart, the team said.

North America divided

When these ornithomimosaurs were alive, North America was split in two by the Western Interior Seaway, a vast body of water that separated Laramidia in the West from Appalachia in the East.

In Appalachia during the late Cretaceous, vertebrate remains "tumbled through rivers and streams before they finally got into sea sediments. So they really went through the rock tumbler before they ever got to the ocean and estuaries and things like that," Gregory Erickson, a paleobiologist at Florida State University in Tallahassee who was not involved with the study, told Live Science.

As a result, fossils from this period in Appalachia are often scrappy, he said.

"I applaud them [the researchers] for being conservative, too, and not trying to name a new species on scraps that are probably not that diagnostic," Erickson said.

Despite the fossils' poor preservation, the researchers "did a really nice job of looking at these materials and definitively showing that they are ornithomimids," Erickson said. "These are important specimens in the sense of trying to figure out what kind of radiation the dinosaurs basically isolated on the East Coast were doing."

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.