Glaucoma: Cause, symptoms, treatment and prevention

The cause of glaucoma is unknown, but it is accompanied by high eye pressure.

Glaucoma is a group of eye diseases that can cause vision loss and blindness. Though the cause is not entirely known, many people with glaucoma have high eye pressure. Excess fluid builds up inside the eye, and the pressure eventually damages the optic nerve, the nerve at the back of the eye that sends visual signals to the brain. Glaucoma can happen in one or both eyes.

Around 80 million people worldwide have glaucoma, according to a 2014 review in the journal Ophthalmology, and the disease is the second-leading cause of blindness globally, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In the U.S., about 3 million people have glaucoma, according to the CDC. Although there are a variety of effective treatments that can slow or stop the progression of glaucoma, they can't bring back lost vision.

Types of glaucoma

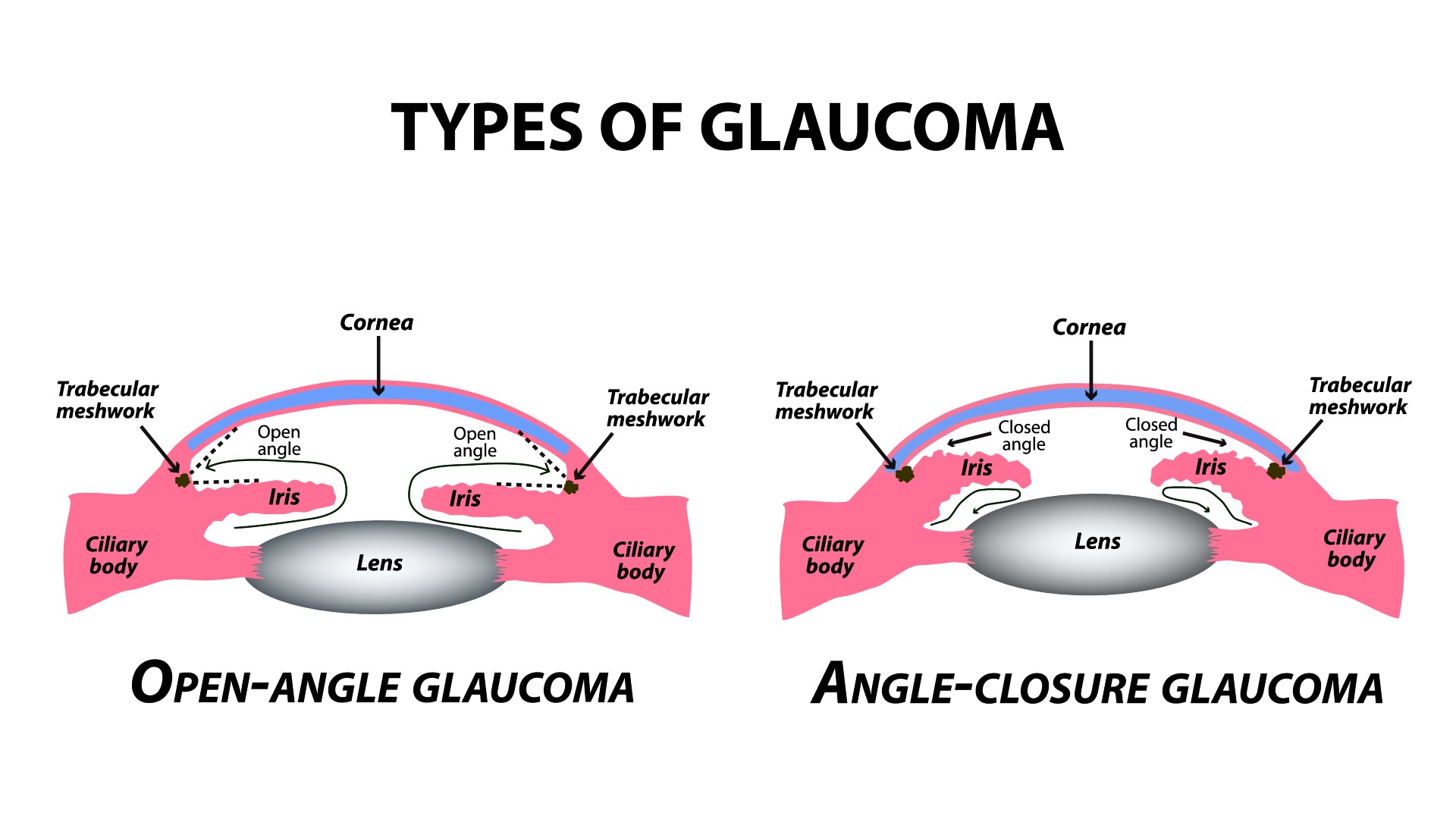

There are two main types of glaucoma: open-angle glaucoma and angle-closure glaucoma.

Open-angle glaucoma is the most common form, affecting 9 in 10 people with the disease in the U.S., according to the National Eye Institute. With this form of glaucoma, the fluid-draining structure of the eye, called the trabecular meshwork, doesn't drain fluid out of the eye properly. Eventually, the fluid builds up inside the eye, leading to increased eye pressure and damage to the optic nerve.

Some people with open-angle glaucoma have a subtype called normal-tension glaucoma, in which there isn't elevated eye pressure but there is still fluid buildup that causes damage to the optic nerve. Experts aren't sure why this happens, but certain health conditions, such as an irregular heartbeat and low blood pressure, can make normal-tension glaucoma more likely, according to the National Eye Institute.

The other main type, angle-closure glaucoma, also called narrow-angle glaucoma, happens when the outer edge of the iris, the colored part of the eye, blocks fluid from draining out of the eye. This form is more common in Asian populations than in people of European and African descent, according to the Glaucoma Research Foundation. If angle-closure glaucoma develops suddenly (called acute angle-closure glaucoma), it is a medical emergency. However, angle-closure glaucoma often develops gradually, which is known as chronic angle-closure glaucoma, according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology.

There are also rarer types of glaucoma. For example, congenital glaucoma occurs when a baby is born with a problem that keeps the eyes from properly draining fluid. According to the National Eye Institute, about 1 in 10,000 babies born in the U.S. has congenital glaucoma. Secondary glaucoma occurs with another medical condition, such as diabetes, high blood pressure, an eye pigment disorder known as pigment dispersion syndrome, cataracts or eye injury.

According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, you might be more likely to develop glaucoma if you have one or more of these risk factors:

- have family members with glaucoma

- are over age 40

- are of African, Hispanic or Asian descent

- have high eye pressure

- are farsighted or nearsighted

- have had an eye injury

- have corneas that are thin in the center

- have thinning of the optic nerve

- have diabetes, migraines, high blood pressure, poor blood circulation or other health problems affecting the whole body

In addition, people taking steroids for any reason, including to treat inflammation of the eye known as uveitis, are at an increased risk of developing glaucoma, because steroids can raise eye pressure, according to the National Eye Institute.

Glaucoma is not contagious.

Glaucoma symptoms

Open-angle glaucoma often has no early symptoms. Eventually, the condition will cause vision loss, starting with the sides, called peripheral vision. Because slight changes in vision can be easy to overlook, and because glaucoma may not affect your vision early on, regular eye exams are crucial for detecting glaucoma.

Acute angle-closure glaucoma, on the other hand, causes sudden symptoms, including severe eye pain, eye redness, decreased or blurred vision, seeing rainbows or halos, headache, nausea and vomiting, according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology. If you think you are experiencing an acute attack of angle-closure glaucoma, you should seek medical attention right away.

In the rare case that a baby is born with congenital glaucoma, there are several signs and symptoms, including sensitivity to light (photophobia), excess tears and fluid in the eye, abnormally large eyes, and eyes that have a cloudy appearance, according to the National Eye Institute. In many cases, congenital glaucoma that is detected and treated early does not result in substantial or any vision loss.

Various types of secondary glaucoma can have their own sets of symptoms. People with neovascular glaucoma, which is caused by vascular conditions such as diabetes and high blood pressure, might notice pain or redness in their eyes in addition to vision loss.

Pigmentary glaucoma is caused by an uncommon condition called pigment dispersion syndrome, in which pigment flakes off of the iris and blocks fluid from draining out of the eyes. Young white men who are nearsighted are most at risk for this type of secondary glaucoma. Symptoms include blurry vision and seeing rainbow-colored rings around lights, especially during exercise, according to the National Eye Institute. Only about 30% of people with pigment dispersion syndrome will develop pigmentary glaucoma, according to the Glaucoma Research Foundation.

Glaucoma treatment

Because glaucoma often has no early symptoms, the only reliable way to diagnose it is an eye exam. The CDC recommends that people in high-risk groups, such as those with diabetes or a family history of glaucoma, get regular eye exams and that everyone get an eye exam by age 40.

Ophthalmologists can do several types of tests to check for glaucoma and its symptoms, according to the Glaucoma Research Foundation. They can check your eye pressure with a procedure called tonometry, which uses a small probe or a puff of air to measure eye pressure. Most people with glaucoma have eye pressures over 20 millimeters of mercury (mmHg).

Ophthalmologists also use a procedure called ophthalmoscopy to directly examine the optic nerve for signs of damage, according to the Glaucoma Research Foundation. For this procedure, doctors first dilate, or enlarge, the pupil using special eye drops. Then, they use a small tool with a light on the end to look through the pupil and magnify the optic nerve at the back of the eye.

An eye doctor might do other tests if they suspect someone has glaucoma, according to the Glaucoma Research Foundation. For example, they might perform a perimetry test, which examines a person's field of vision, since glaucoma usually affects the peripheral vision first. Or, they may perform a gonioscopy test, which uses a contact lens with mirrors to examine the angle between the iris and the cornea — the clear, protective outer layer of the eye — which determines if someone has open-angle or angle-closure glaucoma. Another test, called a pachymetry test, measures the thickness of the cornea, which can be correlated with eye pressure.

There are several types of treatments for glaucoma. One involves the use of eye drops or oral medications to decrease the amount of pressure in the eye. These medications work by decreasing eye fluid production, increasing fluid flow out of the eye or improving fluid drainage, according to the Mayo Clinic.

There are also different surgeries to treat glaucoma. Various forms of laser surgery can help the eye drain fluid or decrease fluid production. Different types of non-laser eye surgeries can create a way for fluid to drain out of the eye, for instance by making a small opening in the trabecular meshwork or implanting a tiny drainage tube in the eye, according to the Mayo Clinic. Minimally invasive glaucoma surgery techniques are similar, but are done on a microscopic scale, according to the Glaucoma Research Foundation. For congenital glaucoma, various types of surgery can commonly correct the problem causing glaucoma and if done early enough, can preserve all of the eyesight, according to the National Eye Institute.

With treatment, some people with glaucoma have minimal or even no vision loss. However, others may eventually go completely blind, according to the CDC.

Regular eye exams and prompt treatment can help reduce the risk of vision loss from glaucoma. In addition, "maintaining a healthy weight, controlling your blood pressure, being physically active and avoiding smoking will help you avoid vision loss from glaucoma," the CDC notes.

Additional resources

The Glaucoma Research Foundation provides answers to some commonly asked questions about glaucoma and resources for people with low vision.

Bibliography

Boyd, K. (2021, September 22). What is glaucoma? Symptoms, causes, diagnosis, treatment. American Academy of Ophthalmology. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/what-is-glaucoma

Lin, S. C. (n.d.). Glaucoma in Asian populations. Glaucoma Research Foundation. Retrieved March 9, 2022, from https://www.glaucoma.org/gleams/glaucoma-in-asian-populations.php

National Eye Institute. (2021, September 10). Types of glaucoma. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/glaucoma/types-glaucoma

Porter, D. (2021, December 9). What is chronic angle-closure glaucoma? American Academy of Ophthalmology. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/what-is-chronic-angle-closure-glaucoma

Tham, Y. C., Li, X., Wong, T. Y., Quigley, H. A., Aung, T., & Cheng, C. Y., . (2014). Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology, 121(11), 2081-2090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.013

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Don't let glaucoma steal your sight! Retrieved March 9, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/visionhealth/resources/features/glaucoma-awareness.html

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Originally published on Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rebecca Sohn is a freelance science writer. She writes about a variety of science, health and environmental topics, and is particularly interested in how science impacts people's lives. She has been an intern at CalMatters and STAT, as well as a science fellow at Mashable. Rebecca, a native of the Boston area, studied English literature and minored in music at Skidmore College in Upstate New York and later studied science journalism at New York University.