Gold: Facts, history and uses of the most malleable chemical element

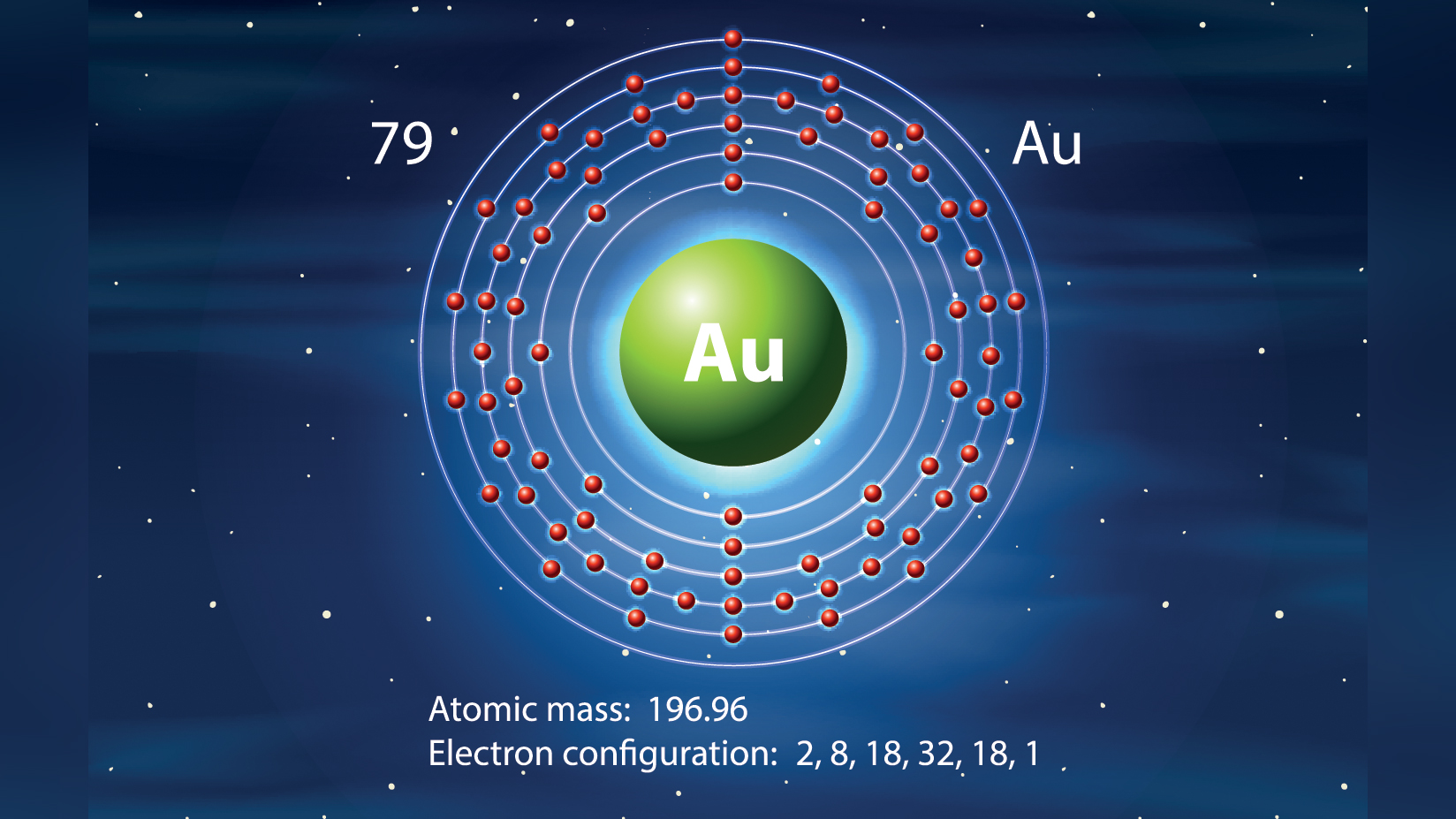

Gold is the 79th element on the Periodic Table of the Elements.

The element gold is a pirate's booty and an ingredient in microcircuits. It's been used to make jewelry since at least 4000 B.C. and to treat cancer only in recent decades. It's in the pot at the end of the rainbow and in the coating on astronaut visors. Gold is an element that bridges old and new — and myth and science — seamlessly.

Properties of gold

Gold, the 79th element on the Periodic Table of the Elements, is one of the more recognizable of the bunch. It is malleable and shiny, making it a good metalworking material. Chemically speaking, gold is a transition metal. Transition metals are unique, because they can bond with other elements using not just their outermost shell of electrons (the negatively charged particles that whirl around the nucleus of an atom), but also the outermost two shells. This happens because the large number of electrons in transition metals interferes with the usual orderly sorting of electrons into shells around the nucleus.

- Atomic Number (number of protons in the nucleus): 79

- Atomic Symbol (on the Periodic Table of Elements): Au

- Atomic Weight (average mass of the atom): 196.9665

- Density: 19.3 grams per cubic centimeter

- Phase at Room Temperature: Solid

- Melting Point: 1,947.7 degrees Fahrenheit (1,064.18 degrees C)

- Boiling Point: 5,162 degrees F (2,850 degrees C)

- Number of isotopes (atoms of the same element with a different number of neutrons): Between 18 and 59, depending on where the line for an isotope is drawn. Many artificially created gold isotopes are stable for microseconds or milliseconds before decaying into other elements. One stable isotope.

- Most common isotopes: Au-197, which makes up 100 percent of naturally occurring gold.

How is gold formed?

Gold represents a tiny fraction of the elements in the known universe. The reason for its rarity is owed to the incomprehensible amount of energy needed for its formation. Gold is formed in stars, but only in those that are exploding in giant supernovas, or incredibly dense ones that have come together in monstrously powerful collisions, according to the journal PNAS .

Stars, such as our sun, generate energy through the power of fusion, where smaller elements are fused, or combined, together into heavier elements. To start with, a star may be mostly hydrogen, the smallest element. The process of fusion under immense pressure and heat in the star's core will generate helium. When hydrogen runs low and the star begins to reach the next phase of its life cycle, it will fuse helium into the next heavier element, and so on.

This process continues until the element of iron, where the balance suddenly shifts. Because fusing iron does not create energy, it consumes it, according to the University of Oregon. With no means of generating internal energy to counteract its own immense pressure and gravity, the star begins to collapse onto itself. If the star is large enough the result is a supernova — a massive star explosion, according to NASA. Heavier elements are formed during the incredible energy generated during this process, including gold.

Related: How can a star be older than the universe?

Gold throughout history

From Eastern Europe to the Middle East to the tombs of Egyptian Pharaohs, gold appears throughout the ancient world. Five thousand years ago, the massive Nile River was the key to the ancient Egyptian empire, according to the Australian government. Its water allowed a bounty of crops to be grown along its edge, keeping its citizens, and its armies, well fed. But there was also a shiny yellow metal that came running down the river, the element of gold. The Egyptians eagerly took this visually appealing treasure and found that because it was naturally pure and malleable, it required little refinement to be turned into mesmerizing decorations.

Gold as a decoration didn't stop at ancient Egypt: A Stone Age woman found buried outside of London wore a strand of gold around her neck; Celts in the third century B.C. wore gold dental implants; a Chinese king who died in 128 B.C. was buried with gold-gilded chariots and thousands of other precious objects.

Gold swiftly came to be a symbol, and unit, of wealth, and it has maintained this allure through time and around the globe. Several millennia after the Egyptian pharaohs and their tombs of gold, the Aztec Empire's gold riches were plundered by the Conquistadors who sought the valuable metal for their own. Later still, workers flocked to Western coast of the United States to take part in the California "gold rush", seeking their own fortunes, according to National Geographic. Therefore gold has driven humans to diplomacy, mass migrations, and even acts of genocide. Without this metal, our history would be quite different.

Related: Tenochtitlán: History of Aztec capital

Gold also plays a strong role in Australian history. In the late 19th century, so many flocked to the country to take part in its booming gold rush that the population of Australia tripled. Owing to its pervasive deposits, the country is still mined for the metal today, according to the Australian government. However, one company, named Evolution Mining, found a different treasure in their hunt for gold. When drilling into the Australian outback's surface in search of gold deposits, the miners instead unearthed sheets of stone that resembled "shatter cones," which form on the outer rims of impact craters. They followed this finding with advanced mapping techniques that allowed the team to confirm the uncovering of a 3.1-mile-wide (5 kilometers) meteorite crater, a finding even more rare than a lode of gold, according to Forbes.

What is a karat of gold?

Most gold jewelry isn’t made of pure gold. The amount of gold in a necklace or ring is measured on the karat scale. Pure gold is 24 karats. Bars of gold kept in Fort Knox and elsewhere around the world are considered to be 99.95 percent pure, 24-karat gold.

As metals are added to gold during jewelry-making, the gold becomes less fine and the number of karats drops. For example, 12 karat gold contains 50% gold and 50% alloys by weight.

The word karat comes from the carob seed. In ancient Asian bazaars, the seeds were used to balance scales that measured the weight of gold.

How much gold is in Fort Knox?

To keep up with the country's mounting gold reserves, the United States Bullion Depository opened at the Fort Knox U.S. Army Garrison in Kentucky in 1937. The first shipment of gold arrived from Philadelphia in trains surrounded by military troops.

Fort Knox is framed in steel with walls of concrete. Despite the defense of a 20-ton steel door, a dirty rumor in the 1970s suggested that the gold in Fort Knox was gone. To quell people's fears, the director of the United States Mint guided congress people and journalists through one room of the vault, and its 8-foot-tall stacks of 36,236 bars of gold.

The depository holds about half of U.S. Treasury's stored gold, according to the U.S. Mint. Each bar weighs 400 troy ounces (about 27.5 pounds), according to the U. S. Department of Treasury. One troy ounce equals about 1.1 avoirdupois ounces. The entire stockpile, as of 2021, weighs 147.3 million troy ounces, which is worth about $130 billion at today's prices. Fort Knox held a record amount of gold on Dec. 31, 1941, reaching a whopping 649.6 million ounces, the U.S. Mint reported.

Other important artifacts have also "seen" the insides of Fort Knox. For instance, during WWII, the Declaration of Independence, Constitution and Bill of Rights were sealed inside for protection, being returned in 1944 to Washington, D.C. Other items stored there at some point in history, according to the U.S. Mint include: the Magna Carta; the crown, sword, scepter, orb and cape of St. Stephen, the King of Hungary.

What is fool's gold?

Pyrite, the inferior mineral nicknamed fool's gold, only mimics gold in looks. Pyrite is more common, harder, and more brittle than gold. When crushed into powder, it looks greenish-black, whereas real gold powder is yellow. Pyrite contains sulfur and iron. During World War II, it was mined to produce sulfuric acid, an industrial chemical. Today, it is used in car batteries, appliances, jewelry and machinery.

Although fool's gold can be a disappointing find, it is often discovered near sources of copper and real gold. So perhaps, miner who stops digging once they have a piece of pyrite in hand is the real fool.

Fun facts about gold

- Two-thirds of the world's gold is mined in South Africa, according to Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

- Seventy-eight percent of the world's yearly supply of gold is used in jewelry, according to the AMNH. The rest goes to electronics and dental and medical uses.

- The atomic symbol of gold, Au, comes from the Latin word for gold, aurum.

- Astronaut helmets were equipped with a visor coated with a thin layer of gold. The gold blocks harmful ultraviolet rays from the sun.

- The world's largest gold crystal is the size of a golf ball and comes from Venezuela. The 7.7-ounce (217.78 grams) crystal is worth about $1.5 million.

- Earthquakes can create gold: A 2013 study in the journal Nature Geoscience found that during earthquakes, water in faults and fractures vaporizes, leaving gold behind.

- The first purely gold coins were manufactured in the Asia Minor kingdom of Lydia in 560 B.C., according to the National Mining Association.

- Gold has a number of artificial, unstable isotopes (the exact number depends on the scientist you consult), but occurs naturally only as Au-197.

- You can eat gold … if you really want to. Gourmet shops sell edible gold leaf and flakes that add glitter to everything from pastries to vodka to olive oil. Don't fear for your stomach: The gold isn't digested and just passes right through, according to Edible Gold, a company that sells gold leaf.

How is gold used?

Gold is also used in medicine. The radioactive gold isotope Au-198 can be injected directly into the site of a tumor, where its radiation can destroy tumor cells without much spillover to the rest of the body. In 2012, researchers reported in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that they could link nanoparticles of Au-198 with a compound found in tea leaves to treat prostate cancer. The tea compound is attracted to the tumor cells, keeping the nanoparticles glued to the right spot for several weeks while the radiation treatment occurs. (The method has yet to be tested on humans.)

In some cases, gold nanoparticles are the only way a drug can work. The anti-cancer drug TNF-alpha kills cancer very effectively. Unfortunately, it's also incredibly toxic to healthy cells. However, clinical trials now underway have found that linking TNF-alpha drugs to gold nanoparticles can successfully treat tumors, because the drugs hit their targets directly, according to Benchmarks, an online publication of the National Cancer Institute.

There's just one problem with humanity's continued love affair with gold: Getting it out of the ground. About 83% of the 2,700 tons of gold mined each year is extracted using a process called gold cyanidation, said Zhichang Liu, a postdoctoral researcher in chemistry at Northwestern University in Illinois. This process uses cyanide to leach gold out of the rock that holds it. Unfortunately, cyanide is toxic, and the process is anything but environmentally friendly.

There could be hope for lovers of gold baubles (and electronic circuits and nanomedicine), however. In 2013 Liu and his colleagues reported in the journal Nature Communications that they'd stumbled upon a way to extract gold from ore with benign starch rather than toxic cyanide.

"Actually, we found this method by accident," Liu told Live Science. While trying to fabricate a porous material, the researchers mixed a starch called alpha-Cyclodextrin with gold salts (charged molecules of gold). To their surprise, the gold precipitated out of the solution rapidly.

The team has since patented the method, which easily extracts gold at more than 97% purity in one step, Liu said. They're now working with investors to scale up the process. "Hopefully, we can find a nice, green way to replace the cyanidation process," Liu said.

Additional resources

- Learn more about the California Gold Rush on The History Channel.

- Michael D. Bordo, a professor of economics at Rutgers University, provides a thorough look at the Gold Standard.

- DK and Smithsonian put together a kids book with loads of visualizations about the Periodic Table.

- Learn more about gold mining around the world on the World Gold Council page.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.