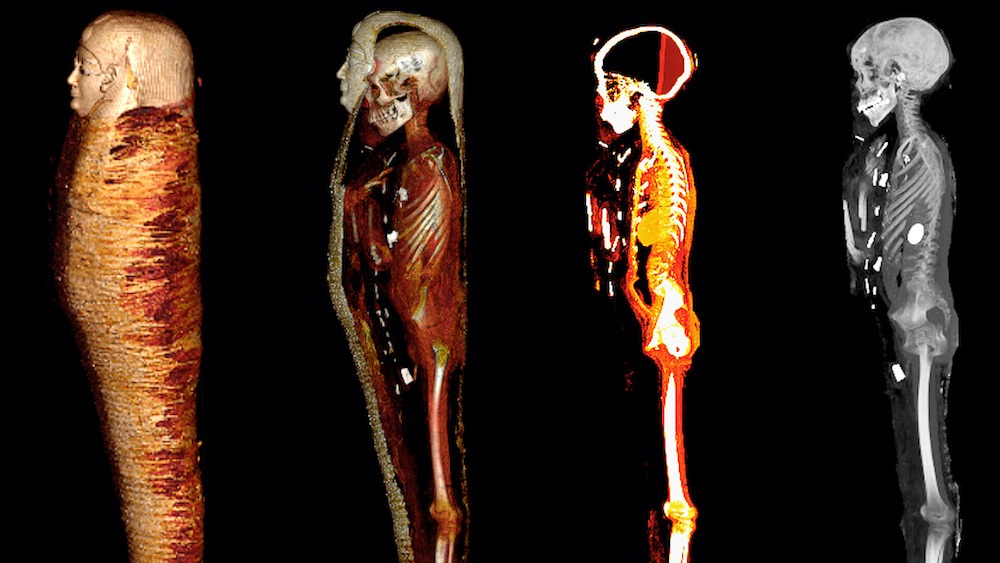

Stunning CT scans of 'Golden Boy' mummy from ancient Egypt reveal 49 hidden amulets

Stunning CT scans of 'Golden Boy' mummy from ancient Egypt reveal 49 hidden amulets

Incredibly detailed computed tomography (CT scans) of the so-called "Golden Boy" mummy from ancient Egypt have revealed a hidden trove of 49 amulets, many of which were made of gold.

The young mummy earned its nickname because of the dazzling display of wealth, which included a gilded head mask found in the mummy's sarcophagus. Researchers think he was about 14 or 15 years old when he died because his wisdom teeth had not yet emerged.

The Golden Boy was originally unearthed in 1916 at a cemetery in southern Egypt and has been stored in the basement of The Egyptian Museum in Cairo ever since. The mummy had been "laid inside two coffins, an outer coffin with a Greek inscription and an inner wooden sarcophagus," according to a statement.

While analyzing the scans, the researchers found that the dozens of amulets, comprised of 21 different shapes and sizes, were strategically placed on or inside his body.

Those included "a two-finger amulet next to the [boy’s] uncircumcised penis, a golden heart scarab placed inside the thoracic cavity and a golden tongue inside the mouth," according to the statement.

Related: Ancient Egyptian mummification was never intended to preserve bodies, new exhibit reveals

The mummy was also wearing a pair of sandals, and a garland of ferns was draped across his body, according to the statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This mummy is a showcase of Egyptian beliefs about death and the afterlife during the Ptolemaic period," Sahar Saleem, the study's lead author and a professor of radiology at the Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University in Egypt, told Live Science in an email.

While researchers aren't sure of the mummy's true identity, based on the grave goods alone, they think he was of high socioeconomic status.

The amulets served important roles in the afterlife.

"Ancient Egyptians believed in the power of amulets … and they were used for protection and for providing specific benefits for the living and the dead," Saleem said. "In modern science, this is explained by energy. Different materials, shapes and colors (e.g. crystals) provide energy with different wavelengths that could have [an] effect on the body. Amulets were used by ancient Egyptians in their lives. Embalmers placed amulets during mummification to vitalize the dead body."

For example, the teenage mummy's tongue was capped in gold "to enable the deceased to speak" and the sandals "were to enable the deceased to walk out of the tomb in the [afterlife]," Saleem said.

However, one amulet in particular stood out to Saleem: the golden heart scarab placed inside the torso cavity. She wound up creating a replica of it using a 3D printer.

"It was really amazing especially after I 3D printed [it] and was able to hold it in my hands," Saleem said. "There were engraved marks on the back that could represent the inscriptions and spells the priests wrote to protect the boy during his journey. Scarabs symbolize rebirth in ancient Egyptians and [were] in the form of a discoid (disc-shaped) beetle."

She added that the heart scarab measured about 1.5 inches (4 centimeters) and was inscribed with verses from "The Book of the Dead," an important ancient Egyptian text that helped guide the deceased in the afterlife.

"It was very important in the afterlife during judging the deceased and weighing of the heart against the feather of Maat (the goddess of truth)," Saleem said. "The heart scarab silenced the heart [on] judgement day so not to bear witness against the deceased. A heart scarab was placed inside the torso cavity during mummification to substitute for the heart if the body was ever deprived [of] this important organ for any reason."

The findings were published Jan. 24 in the journal Frontiers of Medicine.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.