Massive asteroid hit Greenland when it was a lush rainforest, under-ice crater shows

The enormous impact crater dates to 58 million years ago.

Scientists now know the age of an enormous impact crater hidden under Greenland's ice.

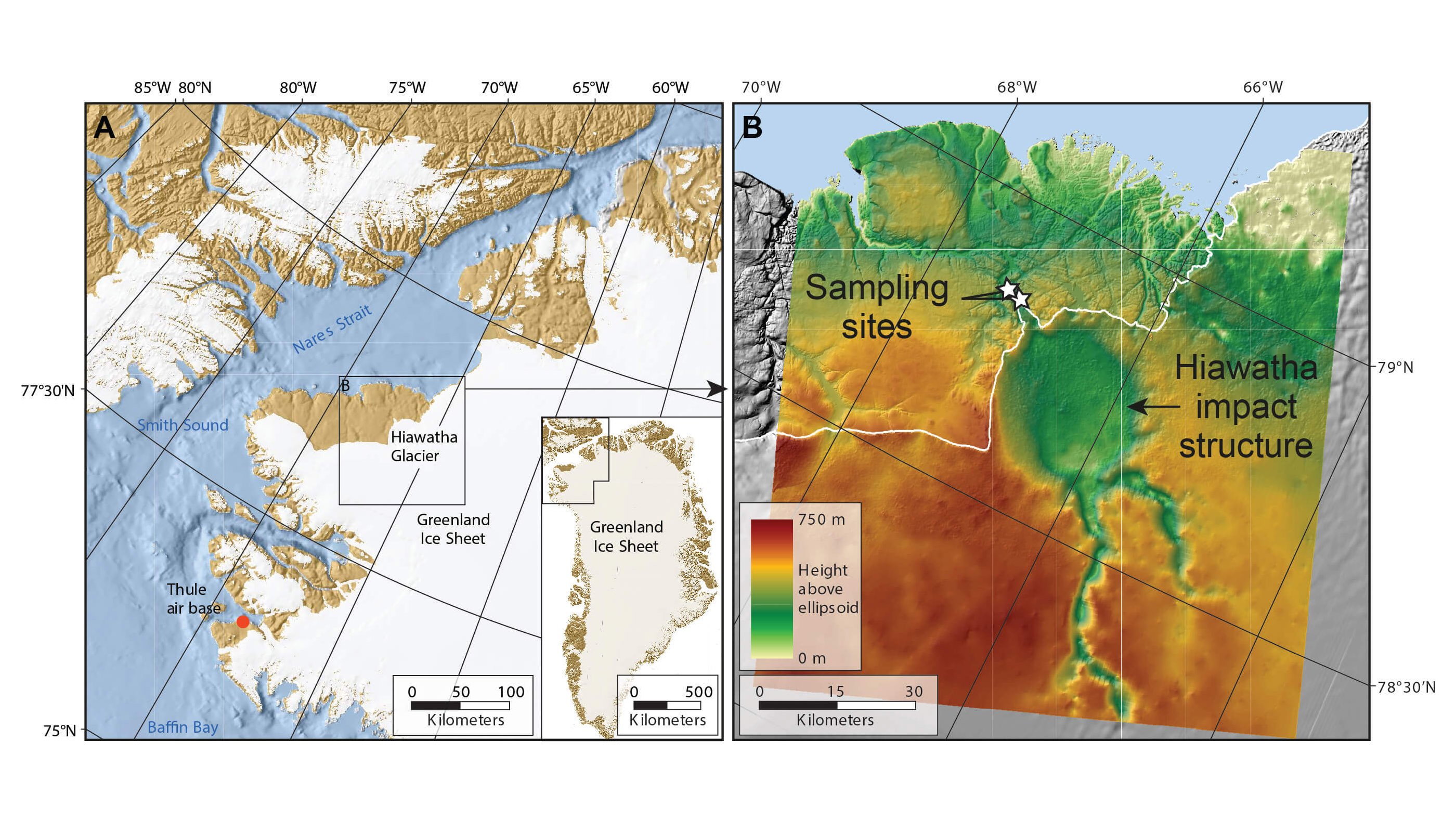

The Hiawatha crater, which sits under 0.6 mile (1 kilometer) of ice in northwest Greenland, formed 58 million years ago, according to a study published March 9 in the journal Science Advances. Whereas some initial estimates had gauged the age of the crater at only 13,000 years, the new finding means the impact occurred much earlier, at a time when Greenland was truly green and full of life.

"Greenland was actually covered with a temperate rainforest when the asteroid hit," said study co-author Michael Storey, a researcher at the Natural History Museum of Denmark who specializes in dating geological materials.

The asteroid was around 0.9 mile (1.5 km) across when it hit the ground. Its impact likely triggered local earthquakes and wildfires, Storey told Live Science, but there's no evidence that it had an effect on the global climate.

The age of a crater

Scientists first discovered the crater in 2018, using ice-penetrating radar instruments mounted to airplanes. But given the massive slab of ice covering the crater, there was no direct way to date the age of the impact.

Related: In photos: The Hiawatha impact crater

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fortunately, the crater sits at the edge of the ice sheet. Just 3 miles (5 km) from the crater rim, a stream flows out from under the ice, carrying sediments with it. After collecting and examining sand grains and larger pebbles from this area, researchers discovered that many had signs of melting and shock — indications that they had been suddenly and rapidly heated.

Storey and his colleagues used a method called argon-argon dating to discern the ages of 50 grains of sand from this stream. This method relies on the natural radioactive decay of potassium 40, a radioactive variant (or isotope) of the element potassium that has a half-life of 1.251 billion years. Potassium 40 decays into argon 40, a gas that remains trapped within the rock. Researchers can measure the ratio between these two isotopes to determine how long the decay has been ongoing. And the extremely slow rate of decay of potassium 40 to argon 40 means that this method is useful for measuring very old ages. The heat of an impact resets this molecular clock to zero, Storey told Live Science, so he and his team could use the numbers to determine when the sand grains were hit.

Meanwhile, study co-author Gavin Kenny, a research fellow at the Swedish Museum of Natural History, used a similar method to measure the decay of the radioactive element uranium to lead in minerals called zircons found within the stream pebbles.

Both methods returned similar findings: The grains and pebbles had been subjected to a major impact about 58 million years ago, during the Late Paleocene.

Local impact

This age means the impact had nothing to do with the Younger Dryas cooling event, a global cold shift that occurred about 13,000 years ago. One controversial theory holds that the cooling event was kicked off with an asteroid impact, but no crater of the right age has ever been found.

Deep-ocean sediment cores have provided a very detailed record of the climate dating back well past 58 million years, Storey said, and there is no indication that the Hiawatha impact caused any global climate hiccups. The impact would have been devastating for the local rainforest flora and fauna of Greenland, Storey said. It may have caused an earthquake of magnitude 8 or 9 nearby and could have sparked massive forest fires. Bolstering that theory, evidence of old charcoal deposits has been found draining from beneath the ice sheets, he added.

"I suspect that Hiawatha, on a sliding scale for asteroid impacts, is somewhere in the middle," Storey said. A space rock the size of the one that made the crater is expected to hit Earth once every 1 million to 2 million years, he said, with a 75% chance that it will land in the ocean rather than on land.

Now that the age of the crater is known, it will be possible to hunt for sediments of the same age nearby and look for evidence of the consequences, Storey said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.