'Massive melting event' strikes Greenland after record heat wave

The rapid melting was caused by an atmospheric event above the ice sheet.

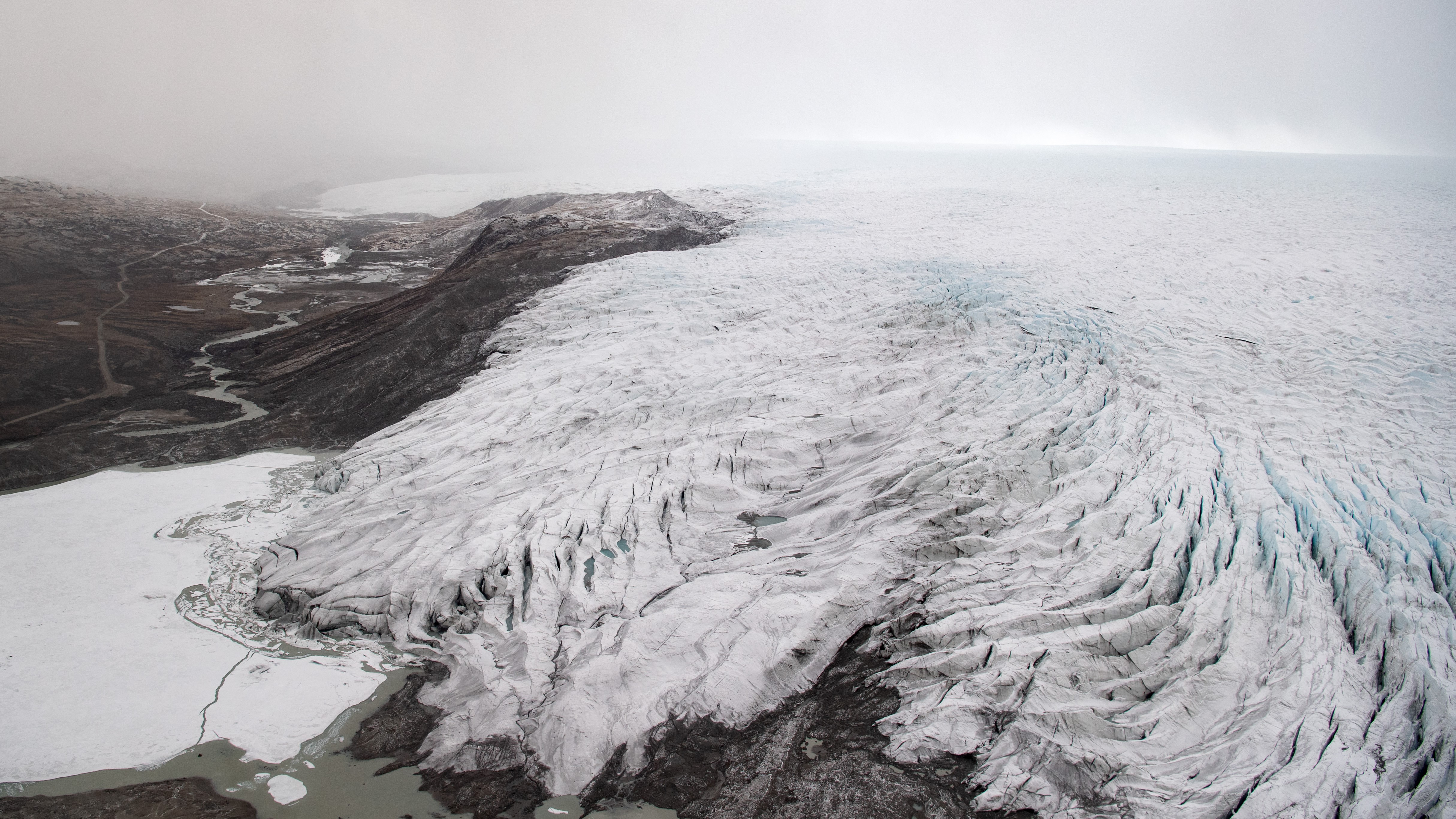

Greenland's enormous ice sheet has been struck by a "massive melting event," with enough ice vanishing in a single day last week to cover the whole of Florida in two inches (5 centimeters) of water, Danish researchers have found.

Since July 27, roughly 9.37 billion tons (8.5 billion metric tons) of ice has been lost per day from the surface of the enormous ice sheet — twice its normal average rate of loss during summer, Polar Portal, a Danish site run by Arctic climate researchers, reported. The huge loss comes after temperatures in north Greenland soared to above 68 degrees Fahrenheit (20 degrees Celsius), which is double the summer average, the Danish Meteorological Institute reported.

High temperatures on July 28 caused the third-largest single-day loss of ice in Greenland since 1950; the second and first biggest single-day losses occurred in 2012 and 2019. Greenland’s yearly ice loss began in 1990. In recent years it has accelerated to roughly four times the levels before 2000.

Related: Images of melt: Earth's vanishing ice

Even though the amount of ice that melted in this summer’s event was less than two years ago, in some ways it could be worse.

"While not as extreme as in 2019 in terms of gigatons, the area over which melting takes place is even a bit larger than two years ago," the Polar Portal researchers wrote in a tweet.

Global sea levels would rise by about 20 feet (6 meters) if all of Greenland’s ice melted, according to an estimate by the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Xavier Fettweis, a climate scientist at the University of Liège, Belgium, estimated that around 24 billion tons (22 billion metric tons) of ice melted from Greenland’s ice sheet on July 28, with 13 billion tons (12 billion metric tons) making its way into the ocean. He tweeted that the other 11 billion tons (10 billion metric tons) of melted ice was reabsorbed "by the snowpack thanks to the recent heavy snowfall."

Fettweis attributes the cause of the acceleration in the day’s melting to an atmospheric event, called an anticyclone, above the continent. Anticyclones are regions of high pressure which enable the air contained within them to sink, warming as it does so while in the summer and creating conditions where hot weather can persist in one area for a long time.

Greenland’s melting season typically runs from June to early September. This year’s melting season has already seen more than 110 billion tons (100 billion metric tons) of ice melt into the ocean, according to Danish government data.

Greenland’s ice sheet is the only permanent ice sheet on Earth besides the one in Antarctica and is roughly three times the size of Texas, with an area of roughly 656,000 square miles (1.7 million square kilometers), according to the NSIDC.

The Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets make up 99% of Earth’s freshwater reserves, according to the NSIDC, but both have been losing mass at an accelerated rate due to climate change. The sheets have lost a combined 7 trillion tons (6.4 trillion metric tons) of ice since 1994, according to a study published January 2021 in the journal The Cryosphere.

Greenland’s trend of accelerated melting is one that scientists are seeing in other icy regions all over the world. Between 2000 and 2019, Earth’s glaciers lost an average of 293.7 billion tons (266 billion metric ton) of mass per year, accounting for 21% of observed sea-level rise across that time period, Live Science previously reported. Another study has estimated that Earth is losing enough ice every year to cover a frozen area the size of Lake Superior, Live Science previously reported.

Originally published on Live Science.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.